Social justice on social media: the impacts of virtual activism

October 27, 2020

Since the Arab Spring demonstrations in 2010, social media and activism have appeared inseparable. As post after post is reshared across platforms like Twitter and Instagram, feeds are filled with calls to action and resources for providing help to various groups. This year, social media is going through a second wave of advocacy, with the number of users participating in activism rising from 45 percent in 2018 to 58 percent in 2020. Similarly, a survey of Redwood students found that 49 percent have partaken in some form of social media activism.

A significant portion of this increase occurred in May, after the video of George Floyd’s death flooded the internet, serving as the catalyst for the reignition of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. In the almost two-week span between May 26 — the day following Floyd’s death — and June 7, the BLM hashtag was used 47.8 million times on Twitter, according to the Pew Research Center. Now, in October, social media activism is being used to raise awareness for a range of social movements as well as current events.

As stated by CBS News, the Generation Z (Gen Z) cohort is revolutionizing activism and is the most politically active generation online. In addition, Gen Z-ers spend the most time on social media, with 90 percent of the generation using these platforms daily in comparison to 69 percent of Gen X-ers. Senior Eva Strage is just one of the many Gen Z-ers who started utilizing their own social media platforms for activism this year. Knowing she would connect with a large audience online, Strage has dedicated many of her posts to the social justice issues she feels passionate about.

“By posting on social media, more people are made aware of what’s happening in the world, and, in a time of such drastic social unrest, the more people that get educated, the better,” Strage said. “Social media does a really good job of getting a lot of people involved and making sure information is reaching a greater group.”

As activism increases online, it continues to take many forms. Petitions, research, articles and other resources are frequently shared to raise awareness for causes ranging from climate change to abortion rights. However, among some educational posts advocating for awareness and change, threatening and hateful language is often directed towards those who present themselves as opponents to the respective movements. Junior Gavin Green has also participated in social media activism and notices the divisive impacts it has.

“[Social media] polarizes opinions because a lot of posts tend to defend one group and attack another. A lot of posts make people want to get defensive because they feel personally attacked, which in some respect is reasonable,” said Green.

In light of social media induced polarization, Green shared a post of his own inviting his peers to research both sides of an argument before taking a strong stance.

“I had people jump to conclusions after seeing my post. All I advocated for was exposure to a well rounded set of viewpoints, yet people automatically assumed I was against them. What I posted was completely neutral, but people still found a way to tell me I was the bad guy,” Green said.

Voicing differing opinions is not often tolerated in Marin. According to psychology teacher Jonathan Hirsch, Marin County has isolated itself through its politically homogeneous environment.

“What matters is not that Marin is a liberal-leaning community, but how homogeneously liberal it appears to be. When people come to the conclusion that intolerance of other points of view is a criteria for belonging, you start to see something called group polarization,” Hirsch said.

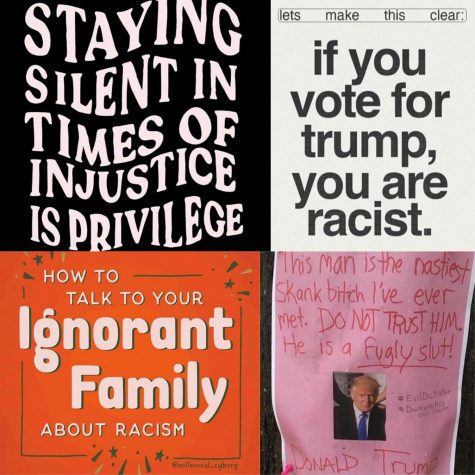

Hirsch explains that it is a common practice to resort to labeling people who share a different point of view on viral movements. Declarations such as “if you vote for Trump, you’re a racist,” and “keep your filthy laws off my silky drawers” are commonly seen on social media and display the increasingly reactionary nature that Hirsch believes leaves little room for rebuttal.

“When [we] stop seeing a diverse set of viewpoints around any issue, we start to assume that everyone thinks the way we do. It creates an ‘us versus them’ mentality because when we go off the assumption that everyone agrees with us, then everyone who doesn’t [agree] becomes ‘them’ and potentially worthy of attack because then they become a threat to our group,” Hirsch said.

The “us versus them” mentality Hirsch explained creates more aggression towards the opposition. However, especially in communities as seemingly politically homogeneous as Marin, the consequences for immoral actions are far more severe than any reactionary language used towards differing viewpoints. During the height of the BLM movement on social media, two former Redwood students were exposed for using racial slurs. One of the first to release the videos of them publicly, class of 2020 graduate Adam Wilson played a large role in initiating the clips’ circulation throughout the community. According to Wilson, it is important to hold people accountable for their actions.

“You need to be straight-up with people who have done wrong. I think what I did was okay because the videos I shared were already available for the public to see and I am allowed to post what I think,” Wilson said.

After these videos were released, a range of responses ensued from the student body that included cyber-bullying, death threats and verbalized intents to vandalize the students’ homes. Many of these responses are examples of the online phenomenon known as “cancel culture,” which is the act of isolating a person from a community for “inexcusable” behavior. Green believes cancel culture takes things too far.

“I think that there needs to be a line drawn between reprimanding somebody and hurting their life. No matter the degree of the mistake, they should never endure any physical harm or be completely alienated from society,” Green said. “It’s not healthy to cut people off super easily for mistakes.”

Senior Israa Mussa is the current president of Students Organized for Anti-Racism (SOAR). As cancel culture becomes increasingly popular, one topic the class and club focuses on is reactions to hateful acts.

“When you get really heated over some kind of act of racism, a lot of times your response in that moment is not the appropriate response. If you took two days to breathe and think about it, that’s probably the appropriate response,” Mussa said.

While cancel culture works to prevent people from getting away with actions from their past, there is a clear difference between “canceling” someone and educating them on how to change. Hirsch understands that although one’s first instinct may be to react out of anger, this type of response almost never leads to the desired outcome.

“While we may not remember what people say, we will always remember how they make us feel. People who have been wronged may seek revenge or retaliation: an eye for an eye. What if it’s revenge on a whole group? Take, for example, police officers. [Say] I’m a very reasonable Central Marin police officer and I have no history of violence or anything other than standing up for people of all color and their rights. If someone says that I’m a part of a group that has wronged them, even if I didn’t, and they take it out on me, that creates an enemy where I could have been an ally,” Hirsch said.

In a time when polarization seems to plague our country, the ways change is propagated are critical. Current methods such as cancel culture and social media activism effectively raise awareness but continue to divide members of our community in the process. However, according to Hirsch, by listening to one another rather than lashing out, education provides an opportunity for growth.