How the pandemic is affecting students’ lives around the globe

September 28, 2020

In Appenheim, Germany, life has begun to resemble normalcy. Sixteen-year-old Killian Kattenbeck participates in sports, hangs out with friends and attends in-person school. The days of quarantining and remote learning are momentarily over despite Europe’s climbing cases, and the pandemic now has little effect on Kattenbeck’s daily life.

Over 4,000 miles away, the clock strikes 4:30 a.m., and Madan Rokaya, also 16, jumps out of bed. Though Nepal is on full lockdown and Rokaya cannot leave his living quarters, he continues to be productive by reading, taking optional classes via Zoom and spending time with the other kids in his group home.

Back in Calgary, Canada, senior Paige Jirka is in the middle of these two extremes. Her school is open, but there are many regulations for her to follow and several COVID-19 outbreaks have been reported.

Here in Marin, high school students are still participating in remote learning, and teachers continue to navigate how to best keep students connected and engaged online. Many sports and extracurriculars remain on hold and social distancing measures are still in place.

With all the changes and obstacles COVID-19 has created, high schools around the world are figuring out the best ways to address ever-evolving situations while still providing an education for their students.

Kathmandu, Nepal – Madan Rokaya

On the outskirts of Kathmandu, Nepal sits a colorful two-story building surrounded by dirt roads and farmland. Perched atop rolling hills, this sanctuary is called the Blind Children Education Center. Fourteen legally blind children live here, most of whom left their rural villages to receive more promising opportunities close to the city. Among these children is Rokaya, who moved from Mugu, a remote village, to Kathmandu and is now at the top of his class in school.

Unlike Marin residents, citizens of Nepal are not allowed to leave their houses to go on walks, take trips to the grocery store or participate in outdoor activities. In abiding by his country’s guidelines, Rokaya has not left the blind home in the last six months.

“At first, I used to be very frightened [about the pandemic]. Now it is simple for me. If we [follow the] proper guidelines given by our government, we will be safe,” Rokaya said.

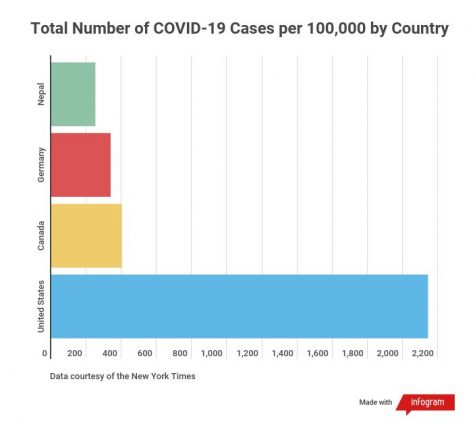

On Sept. 22, Nepal reported an average increase of over 1,100 COVID-19 cases per day, upwards of 65,000 cumulative cases, and a testing rate of 0.36 tests per every 1,000 people, according to Our World in Data, a nonprofit database out of the University of Oxford. In comparison, the U.S. tested 2.39 people per 1,000 as of Sept. 22. Even considering its limited testing opportunities, Nepal has reported significantly fewer cases than its neighboring countries, India and Bangladesh. However, Nepal has been under a strict lockdown since March 24.

While Rokaya has access to a few optional online classes through radio and Zoom, his formal schooling has not resumed since it abruptly halted in mid-March.

“I have been spending time reading various books [like] quiz books and taking online classes. I’m [also] participating in various extracurricular activities,” Rokaya said. “I’m 10 out of 10 bored…I miss my activities and friends. I’m missing school days and other activities.”

Considering how many students at the Blind Children Education Center had to return to their villages in the mountains before the lockdown began, Rokaya considers himself lucky. In a country where only 25 percent of the population has fixed broadband coverage, according to the Nepal Telecommunications Authority, many children cannot participate in online learning, which prompted the Nepali government to shut schools down indefinitely. If schools were to offer remote learning, Royaka says, the government worries that existing disparities between students who have resources to learn online and students who do not would expand.

“[They cannot give us grades on the] basis of power and who has proper access and money; they cannot do proper evaluations. That is very bad for us,” Rokaya said. “We will have passed six months of our school time, and it’s still closed.”

Rokaya currently anticipates the Nepali government’s plan to revise the academic calendar, which may allow schools to start the process of formally resuming. He hopes that 2021 will bring improvement, but does not foresee much change in regards to the lockdown and harsh restrictions.

“If a scientist can bring a vaccine against this disease, then [the lockdown] will be stopped. Otherwise, it will be breeding [for the] next two, three years,” Rokaya said.

Calgary, Canada – Paige Jirka

Six months into the pandemic, twelfth grader Jirka’s life somewhat resembles what it used to. Jirka lives in Calgary, Canada, and her school, Ernest Manning High School, reopened on Sept. 1 after closing on March 13, with its students opting for either online or in-person learning. Jirka, who chose to return to school, estimates about 70 percent of her peers returned to in-person learning as well, a choice all students are required to stick to until Feb. 1.

“I can see why a lot of people would have opted for the online learning option because being in school honestly seems a little bit disorganized,” Jirka said.

Jirka’s school has made several adjustments to prevent an outbreak, including staggering passing periods, during which students must walk outside, and removing lockers, which students have traditionally used to store their winter clothes. While Jirka recognizes her school’s effort to reduce the spread of the virus, she still worries about proper execution and foresight, especially considering the cold winters Canada experiences.

“Having no place to put your coat and boots and also having to walk outside [during passing periods] shows me that the province itself is not even expecting school to be in [session] that much longer. They weren’t thinking about what they were going to do when it’s minus 30 [degrees Celsius] outside,” Jirka said.

Overcrowding also poses a notable barrier. According to Jirka, Ernest Manning was built for around 1,800 students, but it is currently occupied by around 2,500. This overcrowding makes social distancing harder and increases the likelihood and potential severity of an outbreak.

“Each class we’re in has about 40 students, which is quite a bit more than they should. There’s

definitely no social distancing—the desks are way less than two meters [apart] and then you have the crowding in the halls between class changes,” Jirka said.

According to the Alberta province’s official website, nine schools in Calgary had reported an outbreak as of Sept. 23, two weeks after schools reopened. Eight of these schools had reported an outbreak of two to four cases, and one school had reported an outbreak of over five cases. The only time which students have the opportunity to switch between online and in-person learning is in Feb., at the end of the first semester. Otherwise, students must stick to the decision they made at the beginning of the year whether to attend school in person or continue learning remotely.

“They don’t want kids switching from online to in-person [learning in the middle of the school year]. They’ve done basically everything that they physically can to make that legitimately impossible,” Jirka said. “It seems like poor planning in my opinion…We all know this is a situation that changes literally every single day—even every single hour—so kids should be able to react accordingly and say, ‘No, I don’t feel safe anymore. I want to go to online learning.’ But that freedom has basically been eliminated.”

For now, like many seniors worldwide, Jirka just hopes that her school will remain open and safe for the graduation celebrations she has been looking forward to for so long.

“In Canada, we don’t have prom every year. We don’t have a homecoming. All we get is our one big [graduation] ceremony at the end of grade 12. That’s what everyone saves up for and really looks forward to, and [the graduates last year] all missed out on that,” Jirka said.

Appenheim, Germany – Kilian Kattenbeck

“I don’t miss anything [from before COVID-19] because my everyday life is back,” Kattenbeck said.

Kattenbeck lives an hour outside of Frankfurt, Germany, a country that saw success in combating the pandemic over the summer. Even though cases have been steadily rising in Germany recently, much of their country still remains open and their cases remain significantly lower than they were at their peak in late March.

Germany confirmed its first COVID-19 case on Jan. 27 and by March was seeing an average increase of 6,000 cases a day, according to Our World in Data. Following this outbreak, the German government put many practices into effect, including ample contact tracing and a focus on collecting accurate data that was openly communicated with its citizens.

“I’m happy to be in my country because I think Germany is a very good country for [fighting the] coronavirus,” Kattenbeck said.

Kattenbeck has now returned to full in-person schooling. According to regulations that went into effect on Sept. 16 for his district, the Rhineland-Palatinate, Kattenbeck is also allowed to gather in groups of 500 as long as participants adhere to safety measures, which include social distancing and wearing masks when necessary.

“I think [I was most excited] to see my friends [again]. Schoolwork is [also] important. The teachers can explain more to us [in person] than online,” Kattenbeck said.

These changes have not come without opposition, however. Kattenbeck recalls a time when he was worried about stores opening too soon and the virus beginning to spread again.

“The stores were open so early [in April]. Also, in Munich, people went to demonstrate against coronavirus [restrictions]; they didn’t want to wear a mask or social distance,” Kattenbeck said.

At the moment, Kattenbeck is just happy to spend time with his friends again, as he has been for the past few months, a privilege many teenagers around the globe do not have.

As the sun sets and darkness falls over Appenheim, Calgary and Kathmandu, Kattenbeck, Jirka and Rokaya settle in for the night, anticipating the start of a new day and the new normal that the pandemic has created.