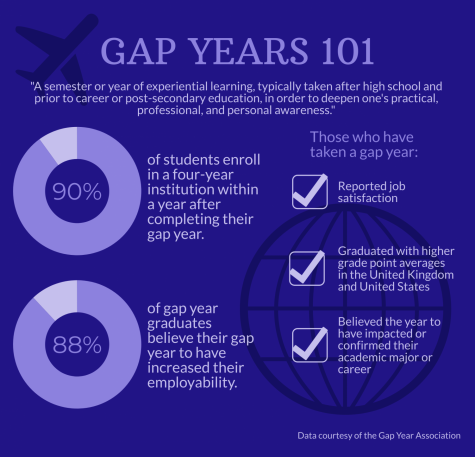

The Gap Year Association defines a gap year as “a semester or year of experiential learning, typically taken after high school and prior to career or post-secondary education, in order to deepen one’s practical, professional and personal awareness.” Historically, about 60,000 college undergraduates took a gap year each year in the U.S., and 90 percent of students enrolled in a four-year institution within a year of completing their gap year, according to the National Review. However, in light of the new coronavirus pandemic and the resulting uncertainty shrouding whether college campuses will reopen for the fall, this number is bound to change.

Senior Natalie Winger knew she wanted to take a gap year before the new coronavirus struck. Because of her dual citizenship in the United States and Norway, she needed to spend a specific amount of time in Norway. For Winger, taking a gap year was the ideal option; in addition to meeting the time requirement, she found there were many other benefits.

“My senior year was less [stressful] because I didn’t have to do college applications. I did work on them, but I wasn’t as stressed to get them done,” Winger said. “I think overall, [taking a gap year] is a better idea because [some seniors] don’t know what we want to do with our lives, especially me right now. Taking a year off to explore and find myself before I start is a good thing.”

Guidance counselor Ian Scott has helped a few students in the past plan their gap years and believes they are a helpful way to ease students who are not yet academically or emotionally ready for college into life beyond high school, allowing students to discover what they want to do with their lives.

Guidance counselor Ian Scott has helped a few students in the past plan their gap years and believes they are a helpful way to ease students who are not yet academically or emotionally ready for college into life beyond high school, allowing students to discover what they want to do with their lives.

“[A gap year] gives you an extra year to prepare either in terms of focus in your academics or just that maturity that comes along with age and a year outside of high school. It can also be beneficial for those students who aren’t exactly sure what they want to do and want to explore the world more,” Scott said.

Becky Bjursten, Redwood’s college and career specialist, has traditionally seen gap years appeal to students who want a new cultural experience or learning opportunity.

“There’s a lot of structured programs that help students, whether it’s to be involved in community service, travel-oriented [or] culturally-oriented,” Bjursten said. “[There are] even ones that focus on adulting, like life skills of learning how to balance finances and checkbooks and how to cook for yourself and live in a community of other students your age.”

For incoming college freshmen, gap years may seem increasingly appealing. A McKinsey & Company report stated that in-person campus life may not return until the fall of 2021, and due to the general uncertainty as to whether college campuses will reopen this coming fall, there has been an increased interest in gap years. Some prospective college students do not have a choice; many are forced into a gap year due to the inability to pay for tuition on account of lost incomes while others simply do not want to lose a part of their overall college experience.

A poll by the Baltimore-based Art & Science Group, a consulting and research firm that presents strategies to higher education, found that almost one in every six graduating seniors are likely to change their plans from attending a four-year college in the fall to taking a gap year. Furthermore, of the 63 percent of students who said they may not be able to attend their first-choice school this fall, 21 percent cited it was unaffordable and 12 percent had personal or familial health reasons. According to Ethan Knight, the executive director of the Gap Year Association, their website’s traffic was up by 150 percent in 2020 compared to the same date in 2019. Though Winger’s gap year has yet to be affected due to the anticipated lift of Norway’s lockdown, Bjursten believes that though the possibility of gap years being affected by the new coronavirus is likely, the virus will affect the activities in people’s gap years as well.

“I think gap years are going to surge in popularity, but they’re going to decrease in availability [a lot] because of the travel component,” Bjursten said. “Gap year programs are probably not going to be able to run if colleges aren’t able to run. So I think abroad travel is going to have a lot more restrictions if it’s even a possibility.”

Despite potential inabilities to afford tuition in light of new unemployment due to the coronavirus, whether gap years’ popularity will increase among lower-income students is questionable because lower-income students have low chances of making money through a gap year during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the National Review.

Consequently, gap years will most likely be more common among wealthier college students, and the financial ramifications for colleges could be drastic if wealthier students decide to defer. 72 percent of college undergraduates received some form of financial aid while 63 percent received grant aid, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s 2015-16 survey.

As a result, colleges are increasingly dependent on the students paying full tuition to not only bring in revenue but to help cover the costs of those receiving non-governmental aid. However, if wealthier students defer to take gap years, colleges’ financial situations could face negative impacts, especially because boarding and athletic programs are already out of operation.

University of California (UC) President Janet Napolitano announced that from mid-March to April, the UC systems’ financial losses related to the coronavirus pandemic already approximated $1.2 billion. Added to potential tuition losses, colleges’ fragile financial situations could create a perpetual cycle in which the lack of incoming full tuitions could result in the depletion of financial aid resources and the potential need to cut down administration workers, halt campus improvement projects or even close their doors forever.

The McKinsey & Company report also predicted the possibility of a decrease in international enrollment, resulting in, when added to those already opting to take a gap year, an overall decline in enrollment for the upcoming fall.

Nevertheless, enrollment may not decrease if past occurrences are any indicator. During recessions, higher-education enrollment has typically increased; the global financial crisis from 2008 to 2009 saw an increase of U.S. undergraduate and graduate enrollment of about 5 to 10 percent each year until 2011. Moreover, more affordable schools with effective virtual learning capacities may face an increase in enrollment, as nearly half of U.S. colleges and universities lacked any official online programs as of 2018, according to the McKinsey & Company report. Bjursten also predicts that due to the many seniors requesting to defer their enrollment, colleges may have to limit the number of deferrals. However, to make up for the increased number of students who decide not to attend college their freshman year, Bjursten guesses schools may over admit in future years.

“I think what you might see happen is [colleges] temporarily have a growth bubble to over admit to have bigger classes. So for some schools, [their] class size might be increasing in order to accommodate any budget deficits that they incur in the future,” Bjursten said. “Potentially, there could be a silver lining for the graduating class of 2021. Maybe schools start to over admit, and so a school that would normally admit 15 percent admits 20 percent, for example. We can guesstimate that those kinds of side effects could happen and pay for any [fiscal] losses that [colleges have] had prior.

Due to the novelty of the situation presented by the coronavirus, increasing uncertainty surrounds previously clear courses in high schoolers’ lives. Time will tell how colleges cope with these new circumstances.