Looking at TUHSD sexual misconduct policies “case-by-case”

June 2, 2020

When Jane was a freshman, a rumor spread around multiple Tamalpais Union High School District (TUHSD) schools that she was involved in a threesome with a male student she had been hooking up with and another female student. When she was a sophomore, a boy in her grade tried to kiss her multiple times at a kickback, and she felt the need to resort to physical methods to defend herself. Last year, a male friend masturbated while giving her what she thought was a casual shoulder massage. Jane, now a current senior in the TUHSD whose name has been changed for anonymity, has no shortage of non consensual and uncomfortable sexual stories. Although these experiences have caused strained relationships between friends, subsequent uncomfortable encounters with the other parties involved and emotional stress, Jane has never considered reporting the incidents to a school official.

“I’m a very low-key person and I don’t think [school officials] would have handled it in a good manner,” Jane said. “Imagine if everyone in my school found out about [the sexual encounters].”

“I’m a very low-key person and I don’t think [school officials] would have handled it in a good manner,” Jane said. “Imagine if everyone in my school found out about [the sexual encounters].”

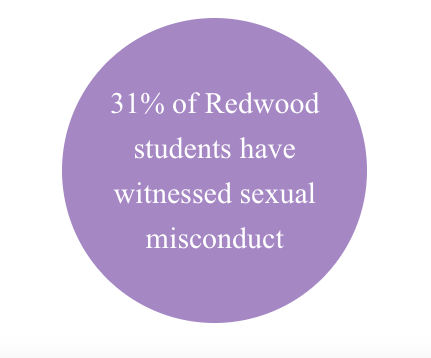

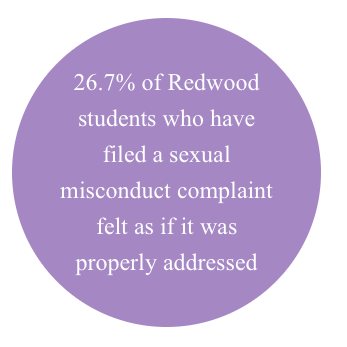

Sexual harassment and assault are a daily occurence in American high schools, with 48 percent of students experiencing some instance of harassment each school year, according to the American Association of University Women (AAUW). According to a self-reported Bark survey, 31 percent of Redwood students have witnessed sexual harassment or assault. Yet only 15 percent have filed a complaint to the school’s administration. Out of the surveyed individuals who filed a complaint, only 26.7 percent felt that their situations were adequately addressed. While it is difficult to determine specific causes of the disconnect between sexual harassment complaints and an appropriate response from school administration, under Title IX, schools are legally liable when they know of sexual harassment but do not address it.

It is no secret that a minority of incidents involving sexual harassment or assault are reported to school administrations, a fact recognized by TUHSD principals.

“Absolutely not [are all incidents of sexual misconduct reported]. And as a woman, I can tell you it’s not,” said Liz Seabury, Principal of Drake High School. “Imagine if everyone in my school found out about [the sexual encounters].” — Jane

Begining in the spring of 2018 following “a public outcry and pleas for help from teachers about sexual harassment,” according to the Marin Independent Journal, TUHSD implemented standardized teacher training and class presentations across schools in the district in an effort to prevent sexual harassment. However, besides these resources and a vague list of procedures provided by the Marin County Office of Education (MCOE), not much is standard about how school administrators respond to sexual harassment and assault allegations. Instead, administrators and district coordinators rely on a “case-by-case” basis to determine the course of action and appropriate punishment following a sexual harassment or assault claim, according to TUHSD principals Seabury, JC Farr (Tamalpais High School Principal) and David Sondheim (Redwood High School Principal). With no strict policy in place, are victims assured that their concerns will be adequately addressed and is there room for inappropriate actions to fall through the cracks?

How administrations enforce rigid steps in a flexible way

According to Seabury, Farr and Sondheim, sexual harassment and assault complaints are addressed on a “case-by-case” basis, meaning there is limited standardization between the way different cases are addressed.

Drake High School receives approximately seven to 10 sexual harassment complaints each school year, according to Seabury. Once a complaint is received, the administration’s following actions are determined in accordance to the severity of the incident basis.

“It really depends, case-by-case, on all the different steps we take,” Seabury said.

Similarly, Sondheim has a specific list of steps taken to address a sexual misconduct complaint, but the resulting consequences are more fluid.

“When we get a complaint, we investigate it. After we’ve investigated, we report it. We determine the consequences if there are any [repeat incidents]. That’s a little more case-by-case,” Sondheim said in November 2019.

TUHSD Superintendent Dr. Tara Taupier affirms that flexible protocols should not be confused with a lack of standards.

“I think there’s a difference between not having standards and following up on a case-by-case [basis]. Everything is case-by-case because no two instances are alike, but we have policies and practices in place that we follow every time a complaint is filed… The evidence comes forward in a way that is unique to each case, then how you respond is predicated on what evidence unfolds,” Taupier said.

According to Taupier, different staff members have different responsibilities when it comes to enforcing sexual misconduct policies.

“The enforcement is on everyone, basically. If you look at it, teachers are mandated reporters, every adult is required to report anything they hear or see, admin is required to follow up and ask them of any report or instance that they see and make sure the policies are being followed. It is up to district administration and the board to ensure that we have up to date policies,” Taupier said.

According to Farr, it is difficult to have a standard protocol for implementing consequences because there are unique elements to every case, such as the severity or if it is a repeated offense, which administrators need to consider.

Generally, the admin will work with district officials to gather information from the parties involved as well as adults who might have witnessed the situation. If they feel like the case is more serious and may be an example of sexual assault rather than harassment, they get the police involved.

With a focus on restoration rather than punishment, the admin and district official will enforce a solution that ranges from conversations between the parties involved to suspension.

“I think it’s important that we provide opportunities for the perpetrator to receive the support needed and also determine a path back into the community and re-establish themselves as a trusted member of our school,” Farr said.

According to Seabury, suspension is only used when a student cannot be trusted to behave appropriately at school.

“We expect you to come to school and behave and treat people with the utmost respect. And if you are sexually harassing another student, we can’t trust you to be at school. So that’s when we really [turn to] suspension,” Seabury said.

However, in Seabury’s experience, most cases of sexual harassment have an underlying cause which encouraged the perpatrator to act inappropriatly. Because of this, Seabury handles sexual harassment with rehabilitation in mind.

“We’re building restorative justice measures. So we always try to take that approach,” Seabury said.

Jane’s fear became Anna’s reality––sexual misconduct is not handled how victims want

“He got on top of me and was trying to hook up with me. I said ‘No, no, I don’t want to.’ He’s feeling me up and I said ‘No, you can’t put your hands in my pants. Stop.’ He put my hands down his pants and tried to make me give him a hand job and tried to make me suck his dick,” Anna, a TUHSD senior whose name has been changed for anonymity, said.

When Anna was a freshman, she was sexually assaulted by a family friend while on a Labor Day beach trip. Her parents found out the next morning and decided not to press charges but severed ties with their friends. All Anna wanted to do was forget the incident and move on. However, psychologically changed from the incident, Anna fell into a rocky pattern that led to skipping classes, panic attacks and anorexia. She dealt with these issues personally, refraining from telling her friends and parents what she was going through. Eventually, one of her teachers noticed she rarely attended class and her grade was suffering as a result. Out of concern, they notified her school counselor who sat down with Anna to find out what was going on.

“I don’t think they were expecting what I was going to say. I told my counselor what happened and she was like, ‘Okay, we’re going to have to call the police,’” Anna said.

Before talking to her counselor, Anna was unaware of the district policy that requires staff to notify authorities if a student was harmed or is planning to harm themselves or another individual.

“It makes sense that they had to call the cops, but if I had known that that was going to happen I wouldn’t have talked to [my counselor],” Anna said. “if I had known that that was going to happen I wouldn’t have talked to [my counselor], — Anna

From there, the investigation escalated and Anna was required to be interviewed by a private investigator in a conference room at school. Later, her and her parents had to be questioned in an interrogation room at a local police station. Simultaneously, her parents encouraged her to go to therapy, and she had weekly weigh-ins with her doctor to address her eating disorder. Anna was disappointed that she could no longer deal with her long-term issues on her own and was uncomfortable with the involvement of other people. Although she was going through the motions of mentally healing from her attack, she was motivated by the prospect of therapy and weigh-ins being over rather than recovery.

While some victims of sexual assault may want to involve their school administrators for a variety of reasons, including ensuring their own safety, others like Anna and Jane prefer to put the incident behind them and work within themselves to avoid dramatic life changes. The possibility of escalating the situation beyond what she felt comfortable with and the fear that she may be worse-off prevented Jane from reporting her experiences with sexual misconduct.

“I don’t think I would have told admin because getting the school involved is a whole different story. It comes with a lot of drama and embarrassment and telling someone that you don’t know is probably really hard,” Jane said. “And then [the perpetrator] gets in trouble, not only with their family…but if they’re in trouble at school, they receive an in-school suspension or it goes on their record, then I’d feel responsible for a lot more than I should feel responsible for. I’d feel worse.”

Unsatisfactory prevention methods leave teachers and students uncomfortable

Although there are limited standards to how TUHSD administrators address sexual misconduct complaints after the fact, there is a rigidly established method for preventing sexual harassment. However, according to teachers and administrators, these methods need to be improved.

TUHSD’s primary method for preventing sexual misconduct is by providing informational presentations and instructing teachers on how to deliver them to students of all grades. According to Redwood English teacher Kendall DeAndreis, the objective of this instruction is for students to understand basic information regarding definitions of highly utilized terms related to sexual misconduct, state laws and the district’s policies.

“I think that the goal [of the presentations] is just for students to understand the state law around sexual harassment, sexual assault and the district’s policy too. And for them to know how to get help and how to access the district policy if they do need to access it, in any way,” DeAndreis said.

However, the district mandated presentations have several shortcomings that have been recognized by both teachers and administrators. In Farr’s opinion, the presentations are outdated and do not reflect student feedback.

“As with any educational resource, it’s subject to review and revision based on student feedback. We’ve implemented the information, and I’m hearing from students that there are gaps in ways that we need to streamline and improve [the presentation],” Farr said.

According to DeAndreis, there is limited to no follow up for students on the presented material after the presentation is delivered or confirmation that the presentation was delivered in the first place. This allows for students to not fully absorb the material and for some students to not receive the required material at all if a teacher forgets to present it.

Additionally, DeAndreis emphasised that sexual misconduct is an extremely sensitive subject matter for both teachers and students. With teachers receiving limited training, it can be uncomfortable to deliver the presentation and foster an emotional connection between students.

“I don’t feel like I’m an expert by any means, and I know that. Sexual harassment and sexual assault goes on at Redwood and in our community and in our country, so I can’t say that

I really feel comfortable. I’ve talked to some other English teachers and they sort of feel the same way,” DeAndreis said.

In addition to the district-mandated presentations, TUHSD schools partner with campus resources to continue sexual misconduct education and foster a comfortable community. At Drake, the Student’s Organized for Antiracism (SOAR) program wears glow sticks during school dances so students can easily find a resource if they feel as if they have been sexually violated and their Peer Resource hosts a workshop around safe sex, harassment and consent, according to Seabury. I think especially now, we need to ramp it up a little bit, — Lyle Belger

Lyle Belger, a senior at Redwood High School and a member of its Peer Resource, says that activities such as condom certification and the “safe is sexy” campaign focus on sexual health but also emphasize the importance of consent.

“Consent has to be given, and it has to be received throughout the entire process. And so while the condom education program is focused on having students know how to put on condoms, it’s also about teaching them that consent has to be there throughout the entire thing. This is more of an underlying theme that students don’t really get,” Belger said.

While Peer Resource programs educate students on the importance of consent during sex, Belger said students learn about what consists of sexual harassment through presentations in freshmen social issues classes as well as the annual presentations in English classes. Personally, Belger does not think the presentations are effective and there’s more that the administration could do to educate students on sexual misconduct.

“I feel like once a year in an hour-and-a-half block period isn’t really going to do it for most students. I honestly can’t remember 95 percent of the presentation…I understand that [admin is] trying [to educate students on sexual misconduct], but I think especially now, we need to ramp it up a little bit,” Belger siad.

Although he recognizes improvement is needed, Farr hopes that educating students about sexual misconduct and consent at school will translate into their social lives.

“We try to do a lot of education because I feel that education is an important piece of prevention and getting the information about affirmative consent and appropriate interactions between students. We try to educate and get the information out into the hands of our student body so that they can make appropriate social decisions,” Farr said.

The national sexual misconduct disaster and Betsy DeVos’s new rule

Sexual misconduct in high schools is a massive national issue, and the ability of school administrators to handle it is an even larger one. As reported by local and national news organizations, a rape victim attended school with her rapist for months in New York, a teacher groped his students for 20 years in Illinois, a 10-year-old boy’s claim that his teacher had molested him were ignored in Michigan. It does not end there. An endless number of instances involving sexual misconduct are unreported across the country. In the past few years, extensive efforts have been taken to prevent and punish sexual assault incidents on college campuses, but not all high school halls have received the same attention.

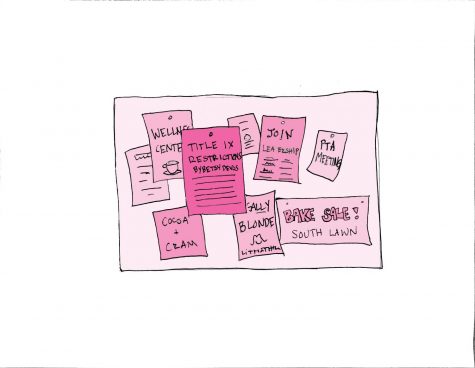

Title IX, a federal law protecting individuals from sex-based discrimination, may seem unfamiliar to some school districts with loose policies that make it easier for sexual misconduct to prevail. Unlike these districts, TUHSD is lucky to have a designated Title IX coordinator, Wes Cedros, who was unavailable to comment on this story. However, in extreme cases, the hands of administrators nationwide are tied by judicial requirements, such as having to comply with incompatible court regulations, and many fear that the new Title IX rule, finalized on May sixth, 2020 by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, would tighten this rope.

According to the AAUW study “Crossing the Line: Sexual Harassment at school,” only nine percent of instances involving sexual harassment in grades seven-12 were reported to an adult at school. The study suggests that this may be because victims did not realize the event’s significance, did not recognize it as inappropriate or did not feel comfortable reporting it. While it is up to schools to implement preventative measures and create an environment that encourages victims to come forwards, Title IX provides legal instructions for what to do after a complaint is made. Administrators should then work with the law to create specific steps that can be implemented and possibly adjusted to fit each individual case. Ideally, this would allow sexual misconduct to be addressed in a confidential manner that maximizes victim comfort and provides appropriate consequences.

Under Title IX, a school district must take immediate action to end, prevent and remediate the effects of harassment after it has been reported or they have been given reasonable belief that an instance of sexual misconduct has occurred. According to an investigation conducted by nonprofit educational news site The 74, there have been cases in which superintendents of school districts did not know they had to comply with Title IX and administrators knowingly did not investigate instances of sexual misconduct. Additionally, because districts are not required to report sexual misconduct, they face limited accountability for enforcing Title IX.

DeVos’s Title IX rule that would take “the important and historic step of defining sexual harassment under Title IX and what it means for a student to report it.” It would also require “schools to respond meaningfully to every report of sexual harassment, and ensures that due process protections are in place for all students,” according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Some significant points of the new Title IX regulation are that it requires schools to offer accessible options to report sexual assualt and “empowers surviviors” to control how a school responds to sexual assault. It also offers equal rights of appeal to both the victim and perpetrator, only considers complaints formally submitted by a teacher or Title IX coordinator and limit the types of allegations subject to Title IX regulations.

Some significant points of the new Title IX regulation are that it requires schools to offer accessible options to report sexual assualt and “empowers surviviors” to control how a school responds to sexual assault. It also offers equal rights of appeal to both the victim and perpetrator, only considers complaints formally submitted by a teacher or Title IX coordinator and limit the types of allegations subject to Title IX regulations.

The rule has been met by wide scale criticism from school administrators, parents and the media who think it would further restrict school districts when evaluating, investigating and resolving sexual misconduct complaints. There are also concerns from victim’s rights organizations such as the National Women’s Law Center that the rule would put too much focus on the rights of the accused rather than the accusers.

Regardless of the new regulations, which will be implemented on Aug. 14, Taupier says TUHSD will continue with its current system of acknowledging and addressing sexual misconduct.

“We’re going to keep doing what we’re doing and we’re going to do the right thing regardless of what the federal government guidelines are. They’ve been a little all over the place in the last couple of years, we’ve had to in some ways fend for ourselves,” Taupier said. “I think just making sure that we are setting policies that speak to the serious nature of it and that we’re going to continue down that path and not make adjustments.”

Although discussing sexual misconduct may be difficult at times, it is an important conversation to have in order to ensure victims have access to all necessary methods of support. TUHSD has a variety of resources, such as Wellness Center counselors and Peer Resource, along with victim support clubs at some schools, that work to uplift victims. Taupier encourages students to take advantage of these resources and is optimistic that the nation’s attitude towards sexual misconduct will improve as the topic becomes less taboo.

“[Sexual misconduct] is a hard conversation to have sometimes because it can be a very nuanced situation. But I think it’s very important and it’s great that we’re gaining greater clarity as a society around it,” Taupier said.