The durability of rape culture on college campuses

March 20, 2020

On the early morning of Sunday, Jan. 18, 2015, Chanel Miller was sexually assaulted just a few hundred feet from the fraternity Kappa Alpha on Stanford’s campus. One year, two months and 12 days later, her assaulter, Stanford swimmer Brock Turner, was found guilty on three felonies: assault with intent to commit rape, sexually penetrating an intoxicated person with a foreign object and sexually penetrating an unconscious person with a foreign object. Just 50 miles away, Redwood students were reacting to this news with a unique perspective; the geographical proximity and closeness in age to the perpetrator and victim almost made it feel like a local issue. At the same time, the whole world watched as Emily Doe—Miller’s pseudonym during the trial—confronted her assaulter and published a powerful victim statement that connected fellow victims across the country and globe.

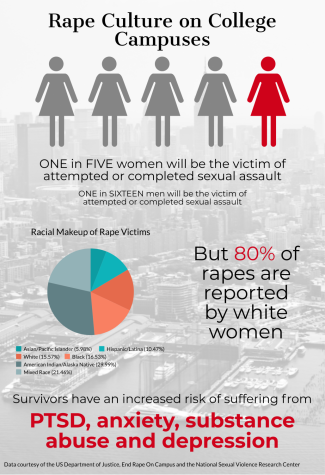

The dangers of sexual harassment and assault are no secret. Many teenagers, girls in particular, are sent off to college with warnings from their parents to never accept drinks from strangers and to always be aware of their surroundings. A study by the University of Mississippi Psychology Department found that 27 percent of college women have experienced some form of unwanted sexual contact. According to the United States Department of Justice, one in five women and one in 16 men will be a victim of completed or attempted sexual assault while in college.

Sharon Inkelas, specialty faculty advisor to the Chancellor of University of California (UC) Berkeley, reports that the administration is aware of the prevalence of sexual violence on college campuses.

Sharon Inkelas, specialty faculty advisor to the Chancellor of University of California (UC) Berkeley, reports that the administration is aware of the prevalence of sexual violence on college campuses.

“I think the main difference [between colleges and the rest of society] is that on college campuses people are living and working together. In a workplace, you can go home at night, but on a college campus, the interactions are just more numerous, and there are many more connections between people,” Inkelas said.

In 2018, dozens of Cal students gathered outside of the iconic and prominent Phi Gamma Delta fraternity house, “Fiji,” holding posters that read “Boycott Frats” and “Frat Brothers Are 300 Percent More Likely To Commit Sexual Assault.” The frat brothers responded by posing with the protestors and posting the photos. Former fraternity brother Walker Spence, a senior at Cal who had abandoned the brotherhood because he was tired of making “excuses for [his] own complicity,” posted one of the photos of the fraternity members and protestors with the caption, “Men in our society have, especially recently, shown that they couldn’t give a shit about victims of sexual assault.”

With intense reputations of hazing and partying, fraternities are often found in the spotlight for sexual assaults on campuses.

“For undergraduates, a lot of the harm that [was reported] took place in housing. That could be Greek life, it could be a dorm, it could be an off campus apartment,” Inkelas said. “We don’t have data on whether more harm occurs [in Greek life] than elsewhere. Alcohol is a risk factor for harm. And to the extent that there are parties with a lot of alcohol—whether they’re in Greek life or elsewhere—that is a risk factor.”

In accordance with Inkelas’ claim, a Clemson University study found that 75 percent of self-reported perpetrators of sexual violence had ingested alcohol prior to commiting the crime.

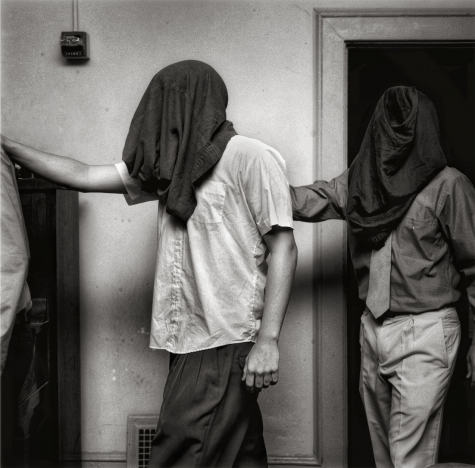

However, it would be inaccurate to state that campus sexual assault is only prevalent in Greek life or that it is only caused by fraternity brothers. According to Greg Barge, former district attorney of San Francisco and former member of the sexual assault task force, one of the many contributing factors to the perpetuation of sexual assault is the culture surrounding victim-shaming and blaming as well as the difficult process of recovery.

“[Victims] constantly search for the reasons why they put themselves in the puzzle. Why was it their fault? They put themselves in the position, or they weren’t aware enough of their surroundings. They were rude to the cashier or didn’t tip enough. [Victims believe] there’s some karmic reason for why they got raped,” Barge said. “It’s not their fault, but they look for reasons [for] why it’s their fault. Those are the things that motivate people to keep things inside. And it’s super, super healthy to have an environment where it has become okay not to keep it inside.”

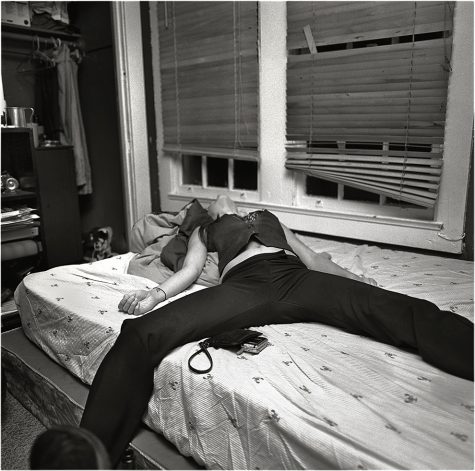

Barge brings up an integral part of the journey of sexual assault: whether victims choose to report the crime or not. Rape is the most under-reported crime with only 37 percent of sexual assaults reported to the police, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. And while the decision of whether or not to report the crime is one of the most difficult, there are also many traumatic decisions to make later during the process of a criminal trial. One of the most difficult parts of this process is what happens right after the crime: the rape kit procedure. This part of the process is important because it is one of the key parts of the investigation and possible evidence. It also largely determines whether or not victims choose to go forward with the process.

“[During a rape kit examination], based on the history that the [victim] gives, swabs will be taken, and they’ll use a black light to go over and illuminate things. But then the [victim] will be asked if [he or] she wants to have it forwarded to the forensics unit for examination,” Barge said. “Some women don’t, and that’s why there will be some rape kits that are not tested because the [victim] will want to be examined, but will not want it to go any farther. And that’s a very, very personal choice, but nobody gets strong armed into doing one thing or another.”

Another obstacle victims face after the crime is the bureaucratic side to law-enforcement and university administration. According to a 2014 study conducted by the United States Senate, 40 percent of colleges and universities reported not investigating a single sexual assault in the previous five years. The same study found that 30 percent of universities offered no training on sexual violence to students or university law enforcement, and 70 percent of universities did not have a protocol for working with local law enforcement.

According to Inkelas, UC Berkeley is working to improve the effectiveness of sexual assault investigations by combining the effort of both the UC Police Department and local law enforcement.

“All of the UC campuses are governed by the UC policy on sexual violence and sexual harassment. If an allegation is made to the Title IX office, they investigate whether [the] behavior violated that policy,” Inkelas said. “And if they do a fact-finding investigation and determine that there was a policy violation, then the case is handed off—according to whether the [offender] is a student or an employee—to the disciplinary process.”

Despite developed policies and procedures on campuses, Dr. Elizabeth Jeglic, professor at the John Jay School of Criminal Justice, believes that there is still much to be improved upon.

“We have to do more to prevent abuse from happening to begin with—such as bystander intervention programs and teaching everyone about affirmative consent and how to practice it,”. Jeglic said in an email interview. “We should provide more resources for those that have been abused so that they can come forward and feel supported through the process.”

Prevention would seem the best solution to sexual violence, as the cost to society is both monetary and psychological. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, rape costs the government more than any other crime at $127 billion every year. This is most likely due to the special resources that victims receive while going through trial, such as an “advocate” that helps speak on the victim’s behalf. On an individual level, the lifetime cost per rape victim is $122,461, according to the American Journal of Preventative Medicine, due to costs such as therapy and other services necessary for mental wellbeing, or lost salary due to court appearances.

UC Berkeley recognizes the benefits of a prevention technique and is developing many programs to achieve this goal.

“The social norms campaign that we’re running is aimed at getting people to understand that others actually hold the same positive values [toward sexual violence prevention] and when you do that you give people the courage to actually act on those values because they seem normal, not unusual,” Inkelas said. “So that’s a way of shifting culture, which is really how we hope to prevent harassment in the future.”

In addition to the multitude of immediate psychological effects, the trauma resulting from sexual assault is long-lasting, according to Dr. Jeglic. A 2007 study from the U.S. Department of Justice stated that survivors experience an increased risk for posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse and depression.

“There is no standard process–each person has their own experience–but many struggle their entire lives after experiencing sexual abuse,” Dr. Jeglic said.

Moving forward, institutions, universities in particular, are moving toward creating programs that help victims recover beyond the initial few months.

“The Path-to-Care Center [at UC Berkeley] also offers healing activities because the trauma of sexual violence can last a very long time even if the case is investigated and the offender is punished,” Inkelas said. “It doesn’t mean that the person who suffered from the harm has healed. So, this Path-to-Care Center devotes a lot of time and energy to that as well.”

Though universities are currently combating the issue, Jeglic, Inkelas and Barge all expressed a similar sentiment on the positive impacts of open communication and discussion of topics that were previously avoided.

“I think that we should teach everyone similarly to respect one another. Teach consent starting from an early age and teach healthy sexuality. Learn that there are adults in their lives who will believe them if they feel uncomfortable and support them if they report abuse,” Dr. Jeglic said.