But what about the boys?

How societal stigmas have contributed to a national emotional epidemic

March 18, 2020

“[My brother] was three years older than me and was a pretty typical example of somebody who on the outside is really well adjusted and really successful. This is somebody who was near the top of his class in high school and went to Wesleyan and then Columbia Law School. He went to work for a big corporate law firm in New York city afterwards. By lots of conventional measures of success, he was really flying high,” English teacher John Blaber said. “But he was not a happy person and, like me, he was raised at a time when you didn’t seek help for depression and anxiety. So he self-medicated with alcohol and struggled and struggled and then eventually got to the point where he took his own life before the age of 40.”

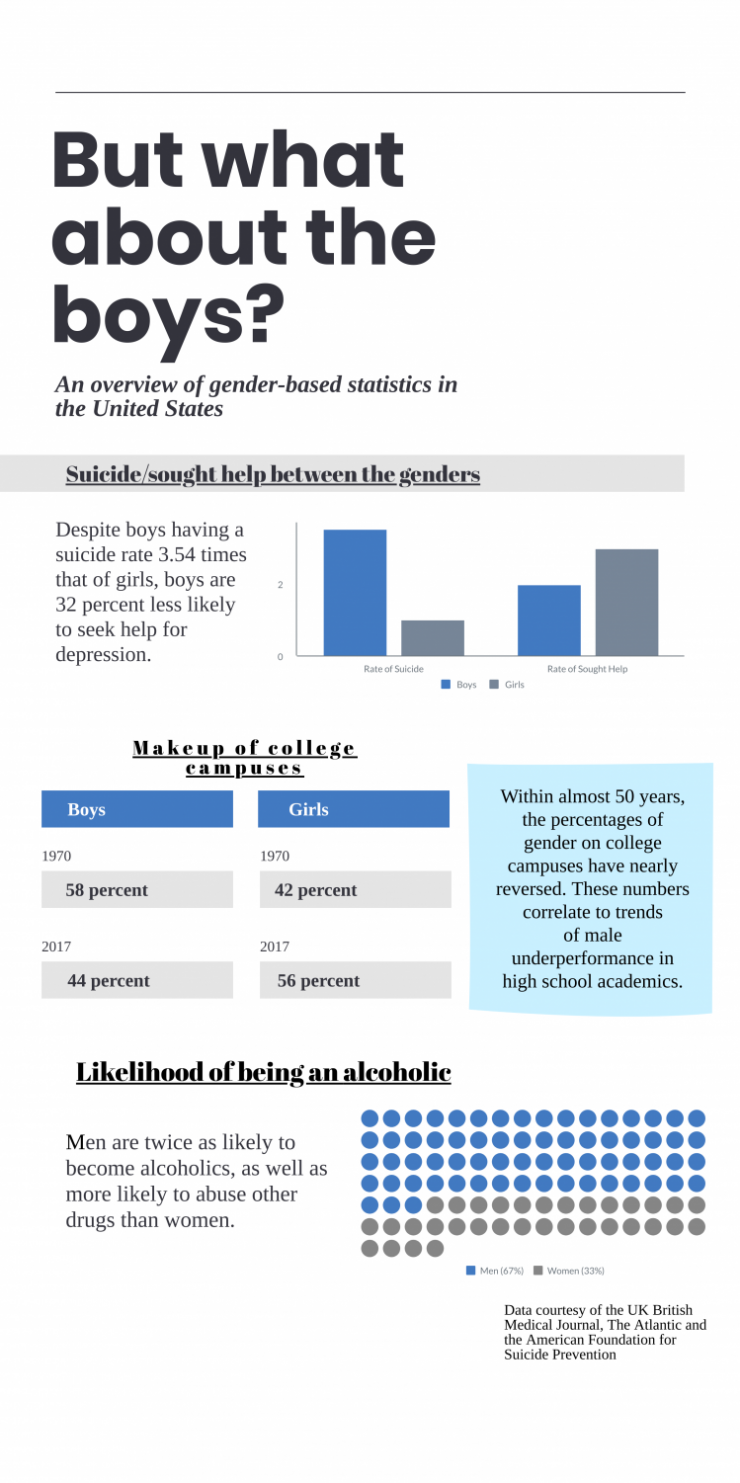

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, men committed suicide 3.54 times more often than women in 2017. This figure receives much of its weight from low tendencies among males to report mental health issues; in 2010, the British Medical Journal found that general primary care consultation was 32 percent lower in men than in women. Societal stigmas regarding male vulnerability often limit willingness to seek help. Though he lost his brother 18 years ago, Blaber says boys are still too often conditioned to suppress emotion.

“I think [stigmas are] better now than they were when I was a teenager, certainly. But I still think that there are a lot of remnants of a culture that encourages young men to be strong. This strength looks like not admitting or showing when you are sad, frightened, lonely or those sorts of negative emotions. It seems to be tolerated for guys to show anger, but not negative emotions that have to do with vulnerability,” Blaber said.

For many men, their experience today is defined by numerous stereotypes that can limit the scope of true emotional expression. Some proponents of male emotional awareness and critics of other men’s issues identify themselves with masculism, a men’s movement that is comparable to feminism in its goals. Dr. Warren Farrell, a former leader of a second wave of feminism in the 1970s and now known as the “father of the men’s rights movement,” believes a cause of subduing male emotion lies in historical stereotypes designed to turn boys into soldiers. Given that many generations experienced war, Dr. Farrell says a type of “heroic intelligence” compelled men to play a role in masculinity’s image today.

“Historically speaking, there was this idea that your life was worth less than the country’s benefit. Your life was worth less than protecting your wife [and] family. But if you were disposable, you’d be a hero. And women fell in love with the heroes,” Dr. Farrell said.

Dr. Farrell, a Mill Valley local, was not always an outward champion of masculism. The only man to be elected three times to the board of directors for the National Organization for Women (NOW) in New York, he enjoyed international recognition for his feminist work in the early 1970s. As the decade continued, Dr. Farrell’s research of gender issues began to reveal a great significance in rising divorce rates and its effects on young women and, specifically, its negative repercussions on young men.

Dr. Farrell later departed from NOW as his findings divided him from many skeptical women on the board, but this newfound freedom prompted extensive writing. The college professor and leader went on to author seven books concerning family dynamics and what he describes as “the boy crisis.” He continues to write and conduct couples communication workshops to this day. Dr. Farrell became associated with the men’s rights movement following the release of his early publications, but maintains that he is no more an advocate for men’s rights than he is for women’s rights. Nonetheless, his current work is more focused on curtailing men’s stereotypical roles in society. One of Dr. Farrell’s primary aims is helping men receive some child custody after divorce, as he sees that male influence in a child’s life is integral to their upbringing.

“When I first met [these men], I would feel the energy of angry people who were bitter. Then I would ask them to pull out photos of their children, and they would invariably begin crying,” Dr. Farrell said. “I don’t mean just tearing [up], but crying all over the place once they saw that it was okay to cry in front of me. So what I saw was that behind the anger, or vulnerability’s mask, was sadness.”

Though many masculists work to combat the stereotypes associated with their gender, the movement is often misinterpreted. According to a Bark survey conducted in March, 51 percent of Redwood students who have heard of the men’s rights movement said it carries negative connotations. Much of this may stem from media reports of male violence and hatred.

In 2014, 22-year-old Elliot Rodger stormed through Isla Vista, Santa Barbara, killing six and injuring 14 before committing suicide in his car. What resided behind the anger that fueled the killing spree was perceived sexual and social rejection—the 141-page manifesto he left behind details his disdain for the jocks, “blonde-haired people” and women who dismissed him as unattractive and unpopular throughout high school and college. The document is filled with hateful slurs toward several groups, and media reports often detailed how Rodger became idealized by many misogynist groups because of his language and actions.

Rodger’s hate-filled act bears no excuse. However, his rampage through Santa Barbara sparked an online movement that unfairly portrayed the men’s movement as wholly prejudiced against women. Like Dr. Farrell, many nonextreme leaders of the movement aim to realign with traditional feminist ideas to promote true equality of the sexes and recognize the unique issues of both genders. To Dr. Farrell, the starting point is identifying attitudes and stereotypes regarding male “weakness” versus male “strength” and exploring how emotion ties into both.

At Redwood, societal stigmas around male emotion are clear. Wellness Center Outreach Specialist Cera Arthur sees disproportionate amounts of girls to boys in the center on a daily basis and knows there is no simple fix to male tendencies. However, Wellness works to address these patterns.

“[In general,] I think females just might feel more comfortable walking through the door. There’s this idea that it’s not okay for boys to express how they’re feeling because it makes them seem weak, which obviously isn’t true,” Arthur said.

Within the month, Wellness aims to create a group specifically for boys who wish to speak and connect with one another in a collaborative, benign space. Wellness oversees four such groups already, yet they are primarily occupied by girls. To change this, they have begun recruiting by talking with counselors and teachers to see who would be a willing, productive fit for the group. As Arthur said, however, many boys at Redwood and at large are uncomfortable seeking help.

Her advice for these boys is to find someone they are comfortable with—not necessarily a therapist—but perhaps a friend, teacher, adult or parent that they can express their thoughts with to any extent.

“My hope is that boys, and everyone, know that it’s all okay. Being vulnerable is really brave…[it’s important] to crush the myth that crying or talking about feelings makes you weak, because those things take a lot of strength,” Arthur said.

Senior Sam Abbott, a member of the Peer Resource class, observes the unwillingness to share male emotions on a daily basis as well. Though advocates for masculism can be portrayed in a negative light, Abbott sees that many significant male issues are overlooked.

“Obviously men have a lot of rights in the United States that we don’t have to fight for, but I think there are issues that men face at higher rates than women that aren’t talked about as much. The vast majority of homeless people are men, and academically, men perform lower than women in most cases,” Abbott said. “Even if you look at the makeup of our peer resource class, it’s vastly female; I think it’s two-thirds girls or something like that. I think part of that comes in the fact that boys are less willing to talk about their feelings.”

Blaber also found this to be true in his relationship with his brother.

“He was very, very careful to mask. Whenever we got together, anytime I talked to him on the phone, [at] any family gathering, he was always, I realize now in retrospect, overcompensating by making sure that he was the life of the party,” Blaber said.

According to Blaber, his brother had an easygoing character and would always be cracking a joke. Blaber never truly picked up external indicators that suggested his brother was struggling internally—he was shocked to learn that he completely misread the mental state of someone so close to him.

“That is a regret that I live with, that he was my brother and I didn’t know him as well as I thought,” Blaber said.

Though it may seem that boys inherently lack the ability to express themselves, the opposite, in fact, is true. In a 2016 article from the New York Times called “Teaching Men to be Emotionally Honest,” journalist Andrew Weiner debunks this misconception.

“From infancy through age four or five, boys are more emotive than girls. One study out of Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital in 1999 found that six-month-old boys were more likely to show ‘facial expressions of anger [and joy]’ and ‘tended to cry more than girls.’ ‘Boys were also more socially oriented than girls,’” Weiner wrote. “But we socialize this vulnerability out of them. Once they reach ages 15 or 16, they begin to sound like gender stereotypes.”

Weiner’s assertions reflect exactly what Dr. Farrell has observed in his research and firsthand. Young boys are not born lacking emotivity, but are raised to conform to society’s standards. According to Dr. Farrell’s findings, at the age of nine, boys and girls commit suicide very rarely and about equally. Between the ages of 10 and 14, boys commit suicide twice as often as girls do. Between 15 and 19, boys commit suicide four times as often and between 20 and 25, boys commit suicide five times as often.

“You get a sense that as adolescence happens, male and female norms begin to set in and pressures and stereotypes begin to set in. Girls manifest certain types of problems and boys manifest other problems,” Dr. Farrell said.

Some boys at Redwood look to flip the script. Through a new club called Men Against Gun Violence, vice president Michael Danne has been working alongside fellow junior and founder Jack Watson to discuss the origins of and prevent male gun violence. The issue hits a tender spot at Redwood, given the various bomb and shooting threats that occured just two years ago. By creating presentations for social issues classes, the club aims to combat mental illness and its relation to violence on and outside of campus.

“[Men] tend to act on violence in a different way than females do, and we’re trying to bring awareness to the fact that men commit over 80 percent of all homicidal shootings,” Danne said. “It is mostly a result of toxic masculinity that has been formed as a result of a societal perception of what it means to be a ‘man.’”

To discuss topics such as those brought up by Danne, attend the Men Against Gun Violence club that meets every other Tuesday in Room 237.

If you and/or a friend are experiencing loneliness, negative thoughts or anything internal or external that is bothersome, resources in and outside of Redwood are plentiful. If you do not feel comfortable walking into the Wellness Center or reaching out to students in Peer Resource, there are several assets independent of Redwood, such as the following:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

The Samaritans: (877) 870-4673 (HOPE)

Boys Town Hotline: 800-448-3000

To read more on topics discussed in this article, take a look at the following:

- “The Boy Crisis” by Dr. Warren Farrell and Dr. John Gray

- “The Red Pill” by Cassie Jaye

- “Teaching Men to be Emotionally Honest” by Andrew Weiner