La justicia se deja sin cumplir a medida que aumentan los feminicidios en México

March 16, 2020

Scroll down for English version.

Desplácese hacia abajo para la versión en inglés.

Todos los días, 10 mujeres son asesinadas en México en crímenes de género, y sólo el cinco por ciento de estos casos pasan por el proceso judicial, según el Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Más recientemente, dos casos específicos han provocado mujeres mexicanas a salir en las calles y protestar contra estas injusticias. La primera mujer, Ingrid Escamilla, de 25 años, fue asesinada por su compañero el 14 de febrero. El autor tomó fotos de las partes de su cuerpo después de que las mutilara y las publicó en Twitter. Cinco días después, Fátima Cecilia Aldriguett Antón, de siete años, fue asesinada, y su cadáver mostró que había sido torturada antes de su asesinato. Estos casos se definen como feminicidios en México; el asesinato de mujeres o niñas simplemente por su género.

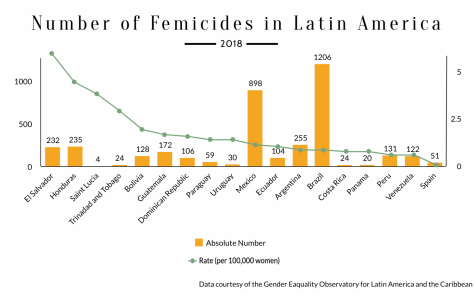

Estas poderosas historias han provocado protestas recientes en México, incluida una huelga nacional el 9 de marzo, el día después del Día Internacional de la Mujer, para demostrar cómo sería México si todas las mujeres y niñas fueran asesinadas. Desafortunadamente, muchas historias de feminicidio rara vez se publican en los medios, lo que significa que innumerables niñas y mujeres muertas nunca recibirán justicia. El gobierno mexicano debería estar haciendo más para prevenir el feminicidio y establecer un ejemplo para el resto de América Latina.

México ha distinguido el feminicidio del homicidio regular desde 2012, según la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito, y otros 17 países latinoamericanos han hecho lo mismo desde entonces. A pesar de que México fue el primero de estos países en establecer el feminicidio como un delito separado, el gobierno debatió eliminar la distinción en febrero, según El País. Estas medidas tendrían sentido si los feminicidios hubieran disminuido en los últimos años, pero sucedió lo contrario. Alejandro Gertz Manero, el fiscal general mexicano, informó un aumento del 137 por ciento en los feminicidios en los últimos ocho años, según BBC Mundo. Aunque los funcionarios mexicanos creen que tratar los feminicidios como homicidios regulares disminuirá su prevalencia, en última instancia hará lo contrario, ya que incluso menos casos se someterán al sistema judicial. Si los feminicidios son tratados de la misma manera que los homicidios según la ley, hace que los delitos de género sean insignificantes en los tribunales, a pesar de que la Corte Penal Internacional los consideró crímenes de lesa humanidad hasta 2016.

Lo más importante que puede hacer el gobierno para ayudar a las mujeres a buscar justicia y erradicar el feminicidio es llevar los casos de feminicidio a los tribunales. Según The Economist, en los primeros 16 meses de criminalización del feminicidio en El Salvador, solo 16 del total de 63 casos fueron resueltos, el resto quedó sin resolver debido a la falta de investigación policial. Este patrón se refleja en toda América Latina, y hay que hacer algo. Una sugerencia sería tratar el feminicidio con más sensibilidad estableciendo tribunales específicos en México que se ocupen de tales casos. Por ejemplo, el derecho de familia no se juzga en el mismo tribunal que los homicidios, y dado que el feminicidio es un crimen increíblemente sensible que implica discriminación, también deben separarse.

También debe haber un consenso legal para el feminicidio en todo el mundo. Si bien existe una definición internacional de feminicidio—“asesinato intencional de mujeres porque son mujeres”—establecida por la Organización Mundial de la Salud, cada uno de los países latinoamericanos que definen el feminicidio en su código legal tienen estándares diferentes. Por ejemplo, para que un asesinato se constituya como feminicidio en México, la víctima debe mostrar evidencia de agresión sexual o mutilación y debe tener una relación cercana con el autor, según la Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos de México. En Chile, los requisitos son aún más estrictos para ser considerado un feminicidio, y la víctima debe ser el cónyuge o el cohabitante del autor, según la Biblioteca Nacional del Congreso de Chile. Estos crímenes atroces contra las mujeres pueden ser cometidos por personas que no tienen una relación con la mujer, y limitar los castigos a estos casos específicos limita el acceso a la justicia.

México debería ser un líder en la lucha por la justicia para estas mujeres en América Latina. Según datos del Órgano Administrativo Descentralizado de la Secretaría de Gobernación en México, ha habido 2,304 casos de femicidio documentado en México en los últimos cinco años, aunque otras cifras de una activista llamada Frida Guerra muestran que 3,142 mujeres y niñas fueron asesinadas solo en el año 2019. Claramente, esos números no se suman. Según el National Catholic Reporter, el gobierno mexicano no considera muchas cosas como los feminicidios, incluso cuando obviamente lo son, y también descarta los casos si no tienen suficientes pruebas para ser considerados feminicidios. Para hacer que los datos sean más precisos, el gobierno mexicano puede trabajar con organizaciones y activistas, como Guerra, para ayudar a definir y contar mejor el número real de casos de feminicidio.

Esta falta de datos sigue afectando a las mujeres mexicanas, incluso hoy en día. Fátima Cecilia Aldriguett Antón e Ingrid Escamilla no son los únicos casos este año; de hecho, según Organismo Administrativo Descentralizado de la Secretaría de Gobernación en México, en los primeros dos meses de 2020 ya se han reportado 384 casos de feminicidio, sin incluir los casos que quedan indocumentados. México puede cambiar este patrón de violencia. Nadie sabe realmente el alcance de este problema debido a la falta de datos precisos. Si el gobierno se enfoca en la educación y la concientización del el feminicidio, todos estos crímenes serían reportados y todas las niñas y mujeres asesinadas por su género podrían lograr justicia.

English: Justice is left unfulfilled as femicide rises in Mexico

Every day, 10 women are killed in Mexico because of gender-based crimes, and only five percent of these cases are ever taken through the judicial process, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Most recently, two specific cases have sparked Mexican women to take to the streets and protest against these injustices. The first victim, 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla, was killed by her partner on Feb. 14. The perpetrator took pictures of her body parts after he mutilated them and posted them on Twitter. Five days later, seven-year-old Fátima Cecilia Aldriguett Antón was killed, and her corpse showed that she had been tortured prior to her murder. These cases are defined as femicides in Mexico; the killing of women or girls simply because of their gender.

These powerful stories have sparked recent protests in Mexico, including a nationwide strike on Mar. 9, the day after International Women’s Day, in order to prove what Mexico would be like if all women and girls were killed. Unfortunately, many stories of femicide are rarely published in the media, meaning countless dead girls and women will never get justice. The Mexican government should be doing more to prevent femicide and set an example for the rest of Latin America.

Mexico has distinguished femicide from regular homicide since 2012, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and 17 other Latin American countries have done the same since. Despite Mexico being the first of these countries to establish femicide as a separate crime, the government debated eliminating the distinction this February, according to El País. These measures would make sense if femicides had gone down in recent years, but the opposite has occurred. Alejandro Gertz Manero, the Mexican attorney general, reported a 137 percent increase in femicides in the last eight years, according to BBC Mundo. Although Mexican officials believe that treating femicides like regular homicides will decrease their prevalence, it ultimately will do the opposite, as even fewer cases will be put through the judicial system. If femicides are treated the same as homicides under law, it renders gender-based crimes insignificant in the courts, even though they have been considered crimes against humanity as of 2016 by the International Criminal Court.

The most important thing the government can do to help women seek justice and eradicate femicide is to actually take cases to court. According to The Economist, in the first 16 months of El Salvador criminalizing femicide, only 16 of the total 63 cases were solved, the rest were left unsolved due to the lack of police investigation. This pattern is mirrored throughout Latin America, and something needs to be done. One suggestion would be to treat femicide with more sensitivity by establishing specific courts in Mexico that deal with such cases. Family law, for example, is not tried in the same court as homicides, and since femicides are an incredibly sensitive crime involving discrimination, they should similarly be separated.

There should also be a worldwide legal consensus for femicide. Although there is an international definition of femicide—“intentional murder of women because they are women”—established by the World Health Organization, each of the Latin American countries that define femicide in their legal code have different standards. For example, for a murder to be constituted a femicide in Mexico, the victim must show evidence of sexual assault or mutilation and must have a close relationship with the perpetrator, according to the Mexican National Human Rights Commission. In Chile, the requirements are even more meticulous to be considered femicide; the victim must be the spouse or cohabitant of the perpetrator, according to the Chilean National Library of Congress. These heinous crimes against women can be committed by people who do not have a relationship with the woman, and restricting the punishments to these specific cases limits access to justice.

Mexico should be a leader when fighting towards justice for these women in Latin America, as they were the first to acknowledge femicide as its own crime. According to data from the Decentralized Administrative Body of the Ministry of the Interior in Mexico, there have been 2,304 cases of documented femicide in Mexico in the last five years, although other figures from an activist named Frida Guerra show that 3,142 women and girls were killed in just 2019. Clearly, those numbers do not add up. According to the National Catholic Reporter, the Mexican government doesn’t consider a lot of things femicides even when they obviously are, and they also dismiss cases if they don’t have enough evidence to be considered femicide. To make data more accurate, the Mexican government should work with organizations and activists, like Guerra, to help better define and count the actual number of femicide cases.

This lack of data is still affecting Mexican women, even today. Fátima Cecilia Aldriguett Antón and Ingrid Escamilla are not the only cases this year; in fact, according to the Organismo Administrativo Descentralizado de la Secretaría de Gobernación en México, in the first two months of 2020, there were 384 reported cases of femicide, not including undocumented cases. Mexico can change this pattern of violence. If the government focuses on education and awareness about femicide, these crimes will not go unreported and all women and girls killed because of their gender can achieve justice.