Marin commits to reducing suicides with county-specific plan

March 16, 2020

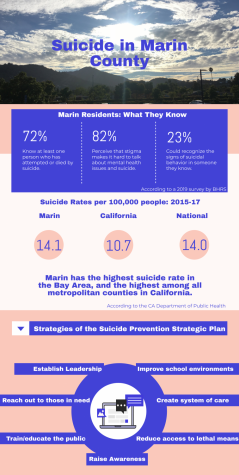

Marin County is widely perceived as a haven for the wealthy, boasting high-quality schools, fantastic weather and beautiful surroundings. But underneath its glamor lies a lesser-known dark side: the county has the highest suicide rate among all metropolitan counties in California. Between 2015 and 2017, 14.1 people per every 100,000 died by suicide in Marin County, significantly higher than the state average of 10.7 over the same period, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Marin County is widely perceived as a haven for the wealthy, boasting high-quality schools, fantastic weather and beautiful surroundings. But underneath its glamor lies a lesser-known dark side: the county has the highest suicide rate among all metropolitan counties in California. Between 2015 and 2017, 14.1 people per every 100,000 died by suicide in Marin County, significantly higher than the state average of 10.7 over the same period, according to the California Department of Public Health.

In the span of just one month in 2017, three Marin County high school students died from suicide. In response, the Marin County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services (BHRS) began the creation of a new Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan (SPSP). In January of 2020, the 124-page report was completed and released, described as “a roadmap for reducing suicide deaths and attempts in communities and neighborhoods countywide.”

Dr. Jei Africa, the Director of BHRS, had two primary objectives for the report.

“There were two basic goals. [We] wanted to relay the message that suicide is preventable…The other that suicide is a public health and community issue. If someone dies by suicide, the whole community is affected by it,” Africa said.

The plan employs seven core strategies, all of which are aimed at preventing suicides. According to Chandrika Zager, a senior program coordinator at BHRS and leader of the SPSP, they attempted to align the plan closely with the state suicide prevention initiative, Striving for Zero, which aims to eliminate all suicide deaths in California by 2025. However, according to Wellness Center Outreach specialist Cera Arthur, Marin poses a unique challenge for suicide prevention.

“The binge drinking rate in Marin is one of the highest in the state for teens and adults, and Marin has really high levels of stress, anxiety and depression,” Arthur said. “There’s a lot of different reasons [for that], but I think one of the main reasons is just the culture of Marin and specifically Redwood that you can’t make mistakes and you have to be the best and succeed.”

In order to address those unique factors, BHRS created a county-specific plan by gathering information about the needs and knowledge of Marin residents. Zager estimated that they conducted more than 1,000 community surveys and 300 school surveys over the course of seven months. One of the surveys’ most important findings was that Marin residents lacked knowledge of how to access support programs and seek help, another reason for the county’s unusually high suicide rate.

BHRS used survey data and worked with outside specialist groups, such as the Resource Developments Associates, to tailor suicide prevention strategies towards Marin. One example of how Marin’s plan will be different from others is the future implementation of a media campaign in order to address the lack of knowledge discovered in the survey.

Another key strategy of the SPSP involves organizing resources, most notably creating the new position of Suicide Prevention Coordinator. BHRS plans to hire someone for that role in the coming weeks or months.

“We’re not saying that the suicide prevention coordinator will solve the problem, but for the first time, we [will] have somebody who’s going to be really accountable and responsible to get the strategies off and running,” Africa said.

Other components of the SPSP include educating Marin County residents about suicide and mental health, reducing access to lethal means of suicide for those deemed at-risk and fostering healthy environments in schools.

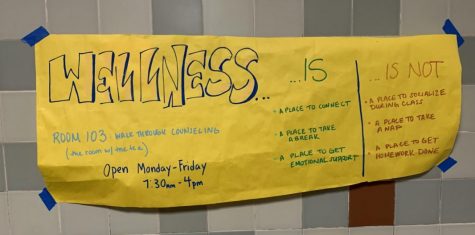

According to Arthur, the bulk of Redwood’s suicide prevention efforts focus on educating freshman classes about the issue, connecting people to therapy and reducing the stigma around mental health issues. Zager described the efforts to be made in schools in the coming months and years, and how Redwood students might see a change.

“We [will] support school connectedness, [which] can impact how people feel in terms of their stress and anxiety levels,” Zager said. “There are strategies around developing coordination of services so it’s more streamlined if a kid needs some support. Building on the crisis intervention supports that are in place and enhancing them, improving parent engagement. There’s a variety of things.”

Africa hopes that in the future, schools and communities will unite and better support those suffering.

“Young people need spaces and places where they can talk about these issues,” Africa said. “The whole community needs to come together and create a climate that is positive.”

If you or someone you know is struggling, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or the Marin Suicide Prevention Hotline at 415-499-1100.