“We live in a racist culture. It is very hard for people…not to express unconscious racism. It’s something that we have to guard against diligently, particularly if we’re white,” Don Carney, director of Marin County’s youth court, said.

Most people, especially in Marin, would say they are not explicitly racist. So, where is Carney’s claim coming from? He is referring to not our explicit but our implicit bias. Implicit bias results from the tendency to process information based on unconscious associations and feelings, even when these are contrary to one’s conscious or declared beliefs.

Not all implicit bias is harmful. In a benign example, if one was instructed to draw a lumberjack, their implicit bias would tell them to draw a man with a bushy beard, wearing a plaid, button-up shirt and suspenders, with an axe by his side. However, the implicit bias that creates the harmless lumberjack stereotype is the same that creates destructive stereotypes for race, sexuality, religion and gender.

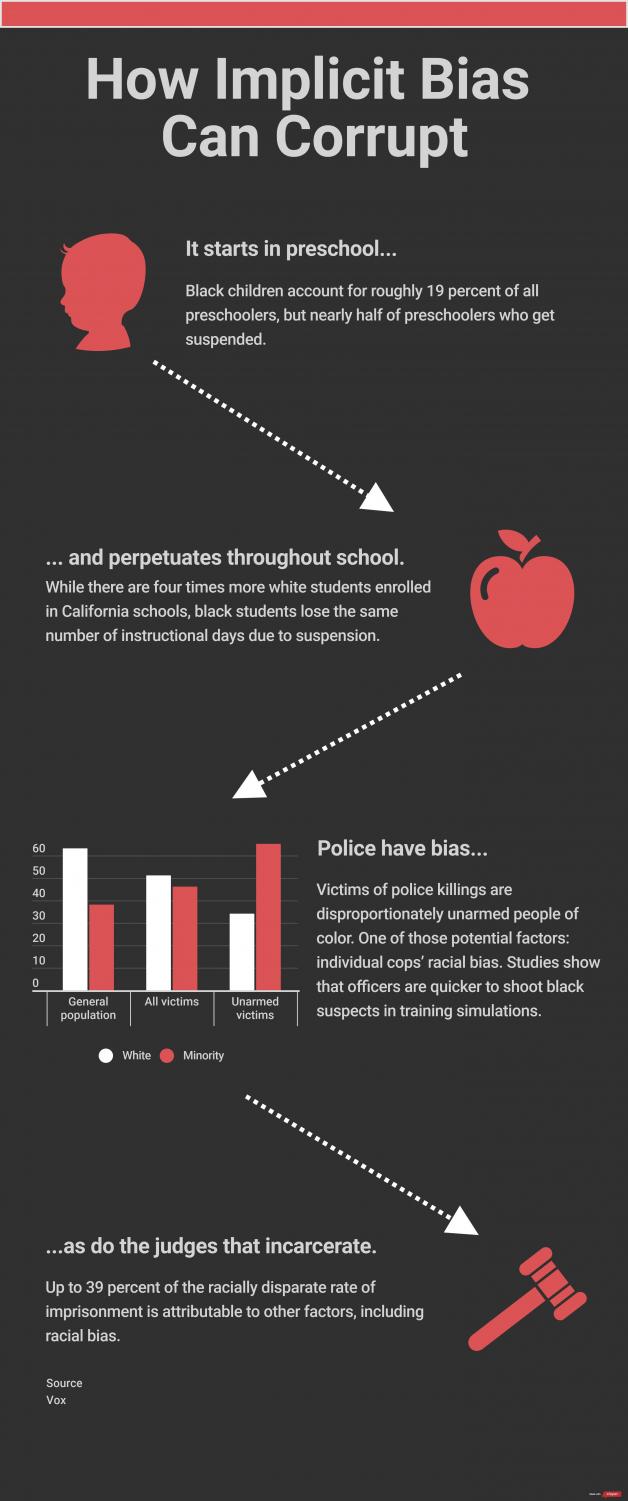

These stereotypes are dominating institutions that were built to provide equal opportunities and treatment for everyone, especially our justice and education systems. Because of this, Carney has made awareness of implicit bias a priority to prevent corruption from occurring in his court proceedings. According to Carney, minorities start feeling the harmful effects of implicit bias as soon as they begin their education.

“[Implicit bias] begins really early—in preschool. Black males are the biggest targets [of implicit bias],” Carney said. “They may not understand it, but they can feel it. Feeling [implicit bias] consistently leads to a young person feeling marginalized, picked on and angry. Then, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy because they’ve been picked on and labeled from such an early age. It creates real problems in the developmental capacities of the young black man.”

Senior Luigyna Parfait has expressed frustration at the level of implicit bias she faces in the school system based on the color of her skin.

“People judge people by the way they look, the way they talk and in their actions without actually getting to know that person,” Parfait said. “I feel like teachers judge me a little bit based on how I look before they get to know me and think I might not do well academically.”

According to recent data from the U.S. Department of Education, black children are 3.6 times more likely to be suspended from preschool than white children. Black children account for roughly 19 percent of all preschoolers, but make up nearly half of all preschoolers who get suspended. As researcher Walter Gilliam suggested for NPR, teachers, both white and black, spend more time focused on their black students, expecting bad behavior.

Likewise, similar bias exists within the judicial system. A study conducted by the University of California, Davis in 2015 revealed that an unarmed black individual is 3.49 times more likely to be shot by police than their white counterparts. In some counties across California, that number can reach a ratio of 20:1, meaning black individuals face a risk factor 20 times greater than the average white individual.

In an effort to combat this behavior, many courts mandate implicit bias education and prevention training for jurors, judges and advocates. Senior Jake Blum volunteers for Marin County’s youth court, a restorative justice program for minors. He has led several implicit bias trainings for youth court volunteers and can attest to the importance of acknowledging one’s own biases.

“Race differences, age differences and class differences all have their own implicit biases—people can’t really apologize for it. That’s why it’s so important to recognize your implicit bias, especially important in youth court, because people come from all different walks of life into the program, and you really have to treat everyone the same,” Blum said.

Specifically, youth court participants have been trained through in-depth conversations on how their unprocessed judgments may affect respondents in court. Furthermore, they have learned how to avoid situations in which these judgments may be unfairly propagated.

“Implicit bias can definitely be dangerous, especially in a situation where someone’s fate is being decided by a group of people. If they’re thought of in a negative light by one of the jurors, then it can really derail the whole situation,” Blum said. “It’s much better for someone to either remove themselves from a situation where they know that they can’t be unbiased or for them to realize what their biases are and try to limit their thoughts against it.”

In recent years, David Minhondo, teacher and advisor of the Students Organized For Anti-Racism (SOAR) club at Redwood High School, has observed how implicit biases can form in Marin.

“Because people are often wrapped up in their own homogenous bubbles, whether that’s your family, community or a place like Marin County—which is around 80 percent white—you don’t often have anything that pushes back on those messages or conveys more positive messages,” Minhondo said.

While recognizing implicit bias is important, it is also necessary to realize that everyone has it; it is inevitable. Seeing a stereotype or commonality perpetuated through music, media or community ideals is guaranteed to manifest into the subconscious—something that Minhondo wants to bring to people’s attention.

“It’s a human condition to be prejudiced, it’s an animalistic thing. You walk into a room, you see a person, you judge them within a millisecond. That is built into our DNA for survival—to see somebody big or weak or strong or small,” Minhondo said. “There are so many things we interpret about people that are built-in anthropologically to us. One of the worst things people can do is see implicit biases [and think] ‘something is wrong with me.’”

The importance in learning about implicit bias does not take root in abolishing the occurrence but instead in acknowledging one’s own inclinations and recognizing how they might affect others. Though judgment is ingrained in human nature, the deriving actions remain fully under an individual’s conscious control and are aspects that can be improved after confronting the subject.

The first steps in recognizing and combating unjust bias can stem from an educational platform. Classes and clubs such as SOAR help dedicated students delve deeper into learning about the effects of racism; however, when such conversations are integrated into a typical classroom setting, these learnings reach an audience that may be severely lacking in such knowledge. English teacher Joe Gonzalez is a strong supporter of allowing students to learn this way.

“Ostensibly anything can lead to a conversation about race. But I find that students can intuit when it feels like this is being forced into a topic or a unit. I try to incorporate talk about race as it fits most appropriately into the unit. One way [to do this] is to be as personal as possible,” Gonzalez said. “For example, in my Language of Humor class, we talked about race as an experience that one has and so that’s a personalized way of thinking about how your race or an experience [because] it can affect what you find funny.”

According to Gonzalez, allowing a situation in which biases are recognized and talked about in an area that lacks diversity such as Marin allows students to begin to understand why these judgments appear in the first place.

“I might be the only middle-class Hispanic person with a professional degree that [students] interact with on a daily basis, whereas most of their interactions with people of color are on the receiving end of some service. I go to Rustic Bakery: the people who are taking the money are white, the people who are working in the back are brown,” Gonzalez said. “That’s not a phenomenon that’s necessarily unique. What that means is that students have limited interaction with people who are different from them, and I try and have them think about that.”

Gonzalez’s tactic of facing bias head-on is not an isolated occurrence but can be used when any member of society wishes to recognize their own biases. Minhondo encourages such individuals in these situations to face hard truths about themselves.

“You have to actually internally view yourself and ask, ‘What do you believe and why do you believe it?’ That frightens many liberals because it forces them to recognize that, yes, although you may do these things that are good, you still have aspects about yourself that need improvement,” Minhondo said.

In the past decade, there has been a large increase in societal attention toward recognizing where disparities exist, exemplified through major movements such as Black Lives Matter. According to a HuffPost/YouGov study, members of the younger generations participate in more protests than any individual above the age of 30. Thus, the ways in which implicit biases are proliferated by the media are beginning to change. Because of this, Minhondo expresses hope for the younger generations and their desire to relieve these disparities.

“I have a three-year-old daughter, and she is now growing up with shows that have people of color. She’s seeing people of color in powerful positions. She’s seeing people of color in a way that I never saw people of color growing up,” Minhondo said. “The implicit biases that she has growing up—I don’t know what those are going to be, but they will be vastly different from [mine].”