Senior in good standing stunts students success

February 14, 2020

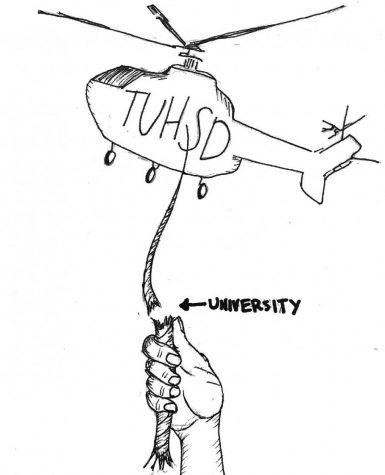

Most seniors leave the structured halls of their high school excited for the perks of college: starting class late, making new friends and feeling the overall freedom of leaving home. However, with the current senior in good standing policy, which closely monitors and controls senior attendance, many students will enter college without the skills needed to harness that freedom and will instead be left drowning in the overwhelming choices that accompany independence.

According to a recent email sent out by administration, seniors can’t have more than four unexcused absences in any class in order to walk at graduation. Though holding students to a high moral standard is a central part of molding teenagers into honest adults, policies that target student attendance stunt the equally important development of decision making skills. This process in turn creates a graduating class filled with many who have based their decisions on consequences set by adults rather than on their own priorities. So what happens to the kid who enters a world where adults are no longer there to set short term consequences?

According to College Atlas, each year 30 percent of college freshmen drop out, while two thirds of the 70 percent of Americans who attend a four-year college will not finish their degree. Though a range of factors from financial restraints to mental health may explain this dropout figure, the helicopter culture of high school also contributes.

The alarm blares in a senior student’s ear as they force themselves out of bed and chug a Yerba Mate. They do this not because of a sense of the long term ramifications that accompany missing class; instead, they are only motivated by the external consequence of not walking at graduation. The senior physically attends all of their classes, checking off all of the administration’s requirements, but they are rarely mentally present, more interested in next weekend’s party than the foreign exchange market or any other topic they encounter in class. Six months later, when a new college student cringes at the blaring sound of their alarm, they won’t feel any pressure to make the right decision, and won’t have developed their own sense of long term decision making that will push them to go to class. This principle, however, goes beyond just school.

According to the National Public Radio, kids with parents who are “so strict that no decision was left to the teenager’s own judgment” were twice as likely to binge drink because they “tend not to internalize the values and understand why they shouldn’t drink.”

If you swap binge drinking for absences and parents for administrators, the concept is the same. Students who are simply told rather than taught to understand the values and rationale behind things–whether it be drinking or ditching class–are less likely to successfully navigate these issues once they enter environments where they must make their own decisions. It is therefore a high school’s responsibility to harness students with self-sufficiency skills even if they allow some students to fail early on, rather than forcibly guiding them to meet arbitrary check marks throughout high school and then sending them off with an inability to achieve those goals on their own.

This pattern of controlling policies in high school is a large part of what causes 25 percent of college students, many of whom once met their high school attendance policy, to skip class in college and in turn become part of the 66 percent of college students who never graduate, according to Spaces for Learning.

According to a meta study by Crede, attendance in college is the most accurate known predictor of academic performance in college, superior to scores on standardized admissions tests such as the SAT, high school GPA, study habits and study skills.

With this in mind, shouldn’t high schools be allowing kids to fail and learn from the real life consequences of truancy within the safer halls of high school, as opposed to keeping them afloat their whole childhood and then abruptly throwing them into the deep end when they graduate?

This doesn’t mean administration shouldn’t have a role in students attendance and that all seniors should be able to ditch as much as they desire. If a student’s GPA is slipping below a 3.0 and their attendance is dwindling, counsellors should meet and discuss how this student can learn from their mistakes and move forward more productively at their own volition, not because of a threat made by adults. However, the current policy is tailored toward short term quotas as opposed to long term understanding and will in turn be detrimental to student’s development beyond the four walls of Redwood.