“There’s a lot of people that would say, ‘Oh my gosh, you smell like Kentucky Fried Chicken.’ I get a lot of comments like that, because biodiesel really smells. It has that smell of, like, you’re going by a burger joint,” biodiesel consumer Michael Willin said.

Michael Willin drives his biodiesel Ford F350, which happens to smell like Kentucky Fried Chicken due to the used frying oil element found in most biodiesels.

According to Biodiesel, the fuel is made from a broad range of feedstocks including used cooking oil, crop oils, animal fats and algae. Biodiesel Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions are on average 80 percent below petroleum diesel, giving millions of individuals an environmental incentive to use the alternative fuel source. Willin started using biodiesel back in 2006 when the California Air Resource Board (CARB) changed the quality of their diesel by removing the sulfur, which was the main component used in order to lubricate the injectors of a diesel vehicle. In turn, this revision required alternative lubricant additives. Biodiesel is not only used as a lubricant additive, but is also a main component of fuel mixtures for sustainable reasons.

“I was looking all around for what’s the best [diesel] additive, and I found out that biodiesel was. It has good lubrication qualities,” Willin said.

Willin then became a loyal customer at what was once LC Biofuels in San Anselmo prior to their closure in 2010. Now, Willin commutes to Biofuel Oasis in Berkeley or uses the unattended pump at Dogpatch Biofuels in San Francisco.

Founded in 2003 by a group of women, Biofuel Oasis has four fuel pumps with a blend of 20 percent biodiesel and 80 percent renewable diesel.

Biofuel Oasis is a biodiesel station and urban farm store. Employee Tess Dufrechou has been working at the cooperative for about three years and proudly drives a biofuel powered Volkswagen. According to Dufrechou, biodiesel is usually $1 more than petroleum diesel, but it is possible for old cars to run on it.

According to Diesel Technology Forum, in 2018, California’s use of biodiesel and renewable diesel fuels eliminated 4.3 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2). Since the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) program began in 2011, biodiesel and renewable diesel fuel have eliminated more than 18 million tons of CO2.

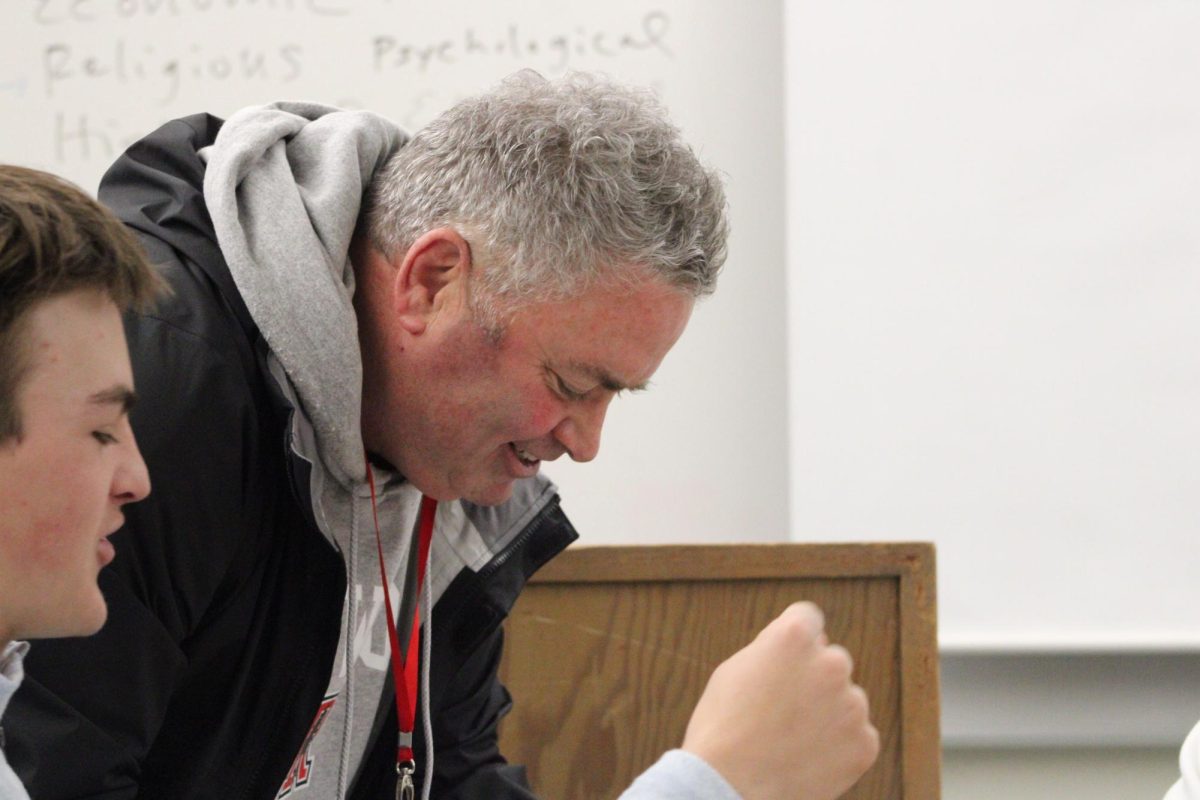

Although biodiesel may seem like an ideal alternative solution to climate change, controversies surround the ethics of the fuel source. For example, if farmers start producing massive crop yields for the sole purpose of creating biofuel (soy and corn are the main crops used to make certain biofuel), that produce is not being used to feed people, and the lack of crop diversity will ultimately deplete the soil. Even if biofuel companies shifted to gathering their product from cooking oil previously used in restaurants, that process isn’t significant enough to sustain entire cities like San Francisco. There’s only so many restaurants that produce enough grease for a biofuel company to collect. AP Environmental Science teacher Mitch Cohen elaborated on the problematic factors of using biodiesel.

“The big problem that I see with biofuels is what plants are you going to use to make that fuel? If you’re taking your best agricultural land and you’re using it to grow food, then you’re putting that food into your gas tank, all you’re doing is mining your soils for your gas tank, and you’re not feeding people,” Cohen said. “If we’re using plants like corn or soy that could otherwise be used to feed people, is that a worthy trade off?”

Clearly there are negative aspects in using biofuel. Though the emissions are significantly cleaner, the source of the fuel may lead to greater environmental damage if it’s not gathered from leftover cooking oil. So what types of solutions do we face?

ExxonMobil, the American multinational oil and gas corporation, is the largest direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil (by 1880, Standard Oil owned or controlled 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining business). They now produce advanced biofuels and algae research, targeting the technical capability to produce 10,000 barrels per day by 2025.

Tess Dufrehou converted to a diesel car and biodiesel fuel since she started working at Biofuel Oasis about three years ago.

According to ExxonMobil, algae can yield more biofuel per acre than plant-based biofuels—currently at about 1,500 gallons of fuel per acre per year. That’s almost five times more fuel per acre than from sugar cane or corn. Additionally, because algae can be produced in brackish and salt water, its production will not strain freshwater resources the way ethanol, a diesel lubricant, does.

The future of biodiesel is slightly ambiguous due to its questionable scalability, affordability and ethical dilemmas. But as individuals like Dufrechou know, the solution to climate change isn’t black and white—there are many actions that must be taken.

“Climate change needs a multiplicity of solutions, and biodiesel isn’t the catch all, but it is a good part of it. It keeps old cars on the road with cleaner fuel. It’s less waste in general, and it takes [cooking] oil waste and makes it into fuel. It’s a pretty sustainable tool and practice…I think it’s part of the [climate] solution, and we should keep going with it,” Dufrechou said.

!["I knew I wanted to be a writer. I wasn't a good student [at Redwood], but I wanted to be a writer, and I wanted to paint. I'm self-taught in all of it, which gave me an original voice," Paige Peterson said. (Photo courtesy of Paige Peterson’s website).](https://redwoodbark.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/ppeterson.png)