Breast Cancer Awareness: the pink marketing ploy

November 12, 2019

Mammogram after mammogram, blood test after blood test, chemo round after chemo round–the treatment of breast cancer can be an excruciating process. Unfortunately, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among Greater Bay Area females. A predicted 27,700 cases of breast cancer will change the lives of people living in California in 2019, according to the American Cancer Society.

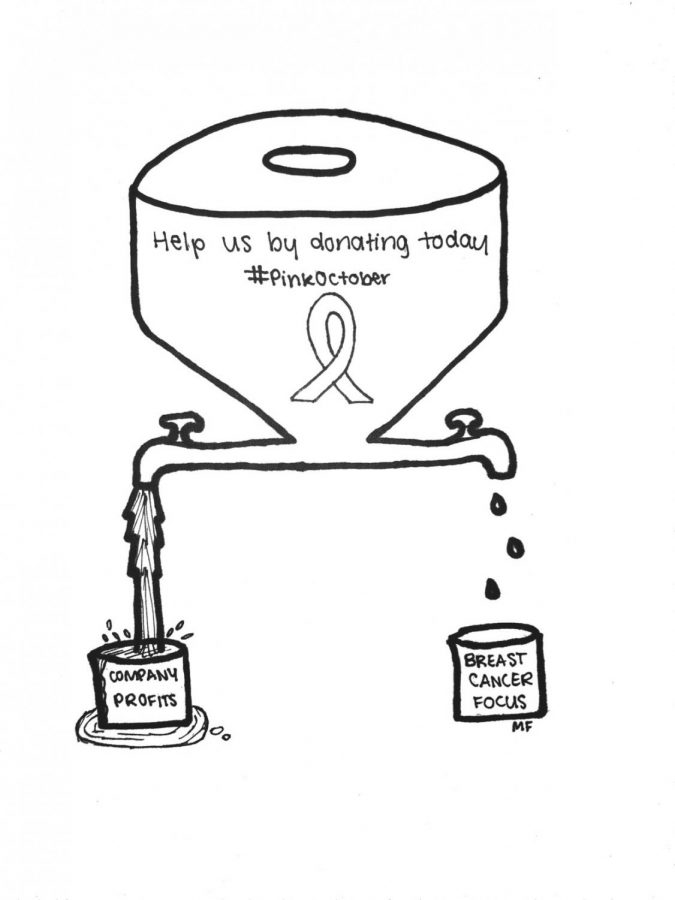

Throughout the month, we see a national support of breast cancer awareness for the annual “Pink October.” While individuals and organizations use the renowned pink ribbon for a good cause, companies and large corporations leverage its “halo effect.” In business terms, the halo effect is a cognitive bias produced to enforce a positive image on a company, which becomes more of an issue when companies have little to no intention of helping the issue.

Organizations like Zero Breast Cancer, a nonprofit organization stationed in San Rafael that promotes breast cancer risk reduction, have to face this conflict year after year. Program director Lianna Hartmour thinks that local community members can advance the actions we take to support the issue.

“A lot of organizations are focused on awareness this month, and we try not to do that, and instead highlight things that are actionable steps that people can do,” Hartmour said.

Every October, I am bombarded by pink shirts, pink pins, Redwood’s mini pink ribbons and posters on storefronts raising awareness for breast cancer, which raises the question: As breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer in the bay area, what is all this awareness really doing?

Jennifer Ginsburg, a local breast cancer survivor, has also brought up the same point. After being incorporated into the breast cancer community, she now views campaigns with a more educated perspective.

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month is a wonderful thing because it encourages women to get tested and early detection is key when it comes to breast cancer,” Ginsburg said. “Unfortunately, the Breast Cancer Awareness campaign has put a little bit too much emphasis on consumption and consumerism.”

Ginsburg has noticed an increasing misuse of the symbol for marketing purposes.

“In many cases, companies who put pink ribbons on their products or make a pink version of their product for October in some cases don’t donate any money to breast cancer research based on any sales of the units of those products,” Ginsburg said.

One of the most well-known examples is the annual National Football League (NFL) football game in support of Breast Cancer Awareness, which raises thousands of dollars in revenue from breast cancer awareness events. However, according to Sports Illustrated, they only donate 0.08% of their profits to cancer research. Still, the NFL’s viewers buy their supportive act, including those in our own community. Sophomore Maisie McPeek is a part of the student events committee on campus and through her planning of the breast cancer awareness day, she has recognized examples of marketing misuse in our local environment.

“I think I see it mostly with athletics, also like a lot of [televised NFL] players around the month of October will wear their pink shoes or their uniforms will be decked out in pink,” McPeek said.

A number of students agree. In a self-reported Bark survey, 75% of students agreed that companies take advantage of Breast Cancer Awareness Month when creating advertising campaigns.

The use of breast cancer awareness as a marketing ploy has become so common that it has developed its own term. Pinkwashing, the exploitation of breast cancer to improve profit or public relations, has become an arduous issue ever since the commercialization of the pink ribbon symbol in the 1990’s. Corporations like the NFL that use this symbol often give next to nothing in donation to charities and organizations associated with the breast cancer movement. In some more extreme cases, companies have ironically worsened the breast cancer problem while marketing the spread of awareness.

Ginsburg has reflected on her increase of consciousness of which companies are benefiting from this advertising strategy.

“I also found out that there were companies who were promoting products as ‘pink ribbon products’ and some of these products were actually carcinogens, meaning they had links to cancer,” Ginsburg said. “Putting a pink ribbon on a personal product, such as a lotion or soap or perfume, that had petrochemicals in it, that had links to cancer was unthinkable to me.”

Though spreading awareness can be helpful to the breast cancer community, it shouldn’t stop there. Hartmour and the rest of the organization have a mission for this year.

“We [at Zero Breast Cancer] hope that people learn actual items they can implement in their own life or in their own communities because actions are all something that individuals can do, but a lot of issues are more systemic,” Hartmour said. “We try to focus on ways that we can make a difference rather than just noticing or caring about breast cancer.”