Starting school later may not be just a dream

September 12, 2019

The potential for change

“Most mornings I have to set five alarms in order to be remotely awake,” senior Chloe Swoiskin said on having to get up for her first period class. “Basically, every morning I’m just tired and don’t want to get out of bed when it’s before eight o’clock.”

California state officials have recently proposed Senate Bill No. 328, an act that would require California middle and high schools to begin after 8:30 a.m. each morning. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), adolescents would benefit from a school starting time of 8:30 a.m. or later to maximize the amount of sleep they receive.

Swoiskin opted out of a first period her junior year, allowing her to come closer to her natural sleep cycle during the school week. As a result, her cognitive abilities improved while at school, and because of this, she strongly supports the bill passing.

“I know a lot of teenagers have a lot of homework, and they have to stay up late… schools assign so much homework, and I do know a lot of teenagers are night people. So I think that the decision to pass that law would be really great,” Swoiskin said.

However, this year Swoiskin is taking a first period, and she is getting less sleep as a result.

“I probably have the same workload, but I’m just so used to going to bed late, I don’t know how to change my schedule,” Swoiskin said.

Because of this, Swoiskin is feeling the consequential results at school, forcing her to drink coffee, which she rarely drank when she had no first period. According to the AAP, a greater use of stimulants such as caffeine and prescription medications are often used to make up for sleep deprivation.

“I love my schedule but having a first period is definitely affecting how much I can focus,” Swoiskin said. “I definitely feel more tired, and I’ll have to nap in my car between classes because I’m just so tired now. I can’t focus.”

The problem

A recent National Sleep Foundation poll found that 28 percent of students admitted to falling asleep in school at least once a week, and over 20 percent fall asleep while doing homework about once a week. Deborah Meshel, the school nurse for the Tamalpais Union School District (TUHSD), can see why it is difficult for students to stay caught up on sleep.

“Most teenagers have after-school activities, and, especially in this district, they have a lot of homework. They could have up to two or three hours of homework or more a night,” Meshel said.  “Between their after-school activities, eating dinner, doing their homework and their sleep cycles not being ready to go to sleep until later, it’s hard for a teenager to get eight to ten hours of sleep when they have to be at school by 8 a.m.”

“Between their after-school activities, eating dinner, doing their homework and their sleep cycles not being ready to go to sleep until later, it’s hard for a teenager to get eight to ten hours of sleep when they have to be at school by 8 a.m.”

In addition, teenagers have further difficulty wake up early because according to the American Psychological Association, homeostatic drive for sleep and the circadian rhythm both influence the sleep cycle. During waking hours, the homeostatic sleep drive develops, eliciting a feeling of tiredness. However, this drive decreases during adolescence. Additionally, the circadian rhythm allows the body to know when to fall asleep. During adolescence, Delayed Phase Preference occurs, in which the time the body feels as though it should fall asleep shifts to be later at night due to a later release of melatonin, a hormone that maintains the sleep-wake cycle.

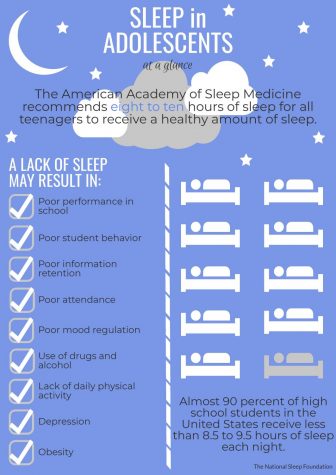

Because of this, according to the National Education Association, the later production of melatonin means that going to bed earlier would not actually benefit adolescents. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommends eight to ten hours of sleep each night for all teenagers to receive a healthy amount of sleep, but a recent National Sleep Foundation poll discovered that 87 percent of United States high schoolers received less than 8.5 to 9.5 hours of sleep, and seniors received an average amount of less than seven hours of sleep on school nights.

“I think it’s a combination of getting more sleep, but also not expecting teens to go to bed earlier but [instead] to have them wake up later,” Meshel said.

Sleep generally benefits learning abilities, emotional temperament, mental health and weight control while a lack of sleep harms information retention, student behavior and mood regulation, according to the American Psychological Association (APA). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine states that adolescents unable to get adequate sleep suffer from obesity, lack of daily physical activity, depression, the use of drugs and alcohol, and poor performance in school. Additionally, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, chronic sleep deprivation increases risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic dysfunction, one of which is type 2 diabetes mellitus.

According to Meshel, TUHSD has high levels of students with stress and anxiety who could benefit from more sleep. Meshel has also noticed a difference between students’ behavior in the morning compared to the afternoon.

“This is just a generalization because some students are morning people, but overall, [in] the classes in the morning, students don’t participate as much and they seem more sleepy at eight o’clock in the morning,” Meshel said. “By the afternoon, they’re more lively, and I think they are more ready to learn. They are able to sit in class and actually soak in the information.”

The benefits of a later start time

According to the APA, studies from a broad range of environments have revealed that schools with later start times have higher attendance, higher GPAs, higher state assessment scores, higher college admissions test scores, higher student attention and less students asleep in class. Additionally, students have less car accidents, less disciplinary action and higher-quality interactions with other students and their families.

Two schools in Seattle, Washington, Franklin High and Roosevelt High, implemented the later starting bells in order to study the outcomes. Researchers at the University of Washington found that the average student gained 34 minutes of sleep, were more actively involved in the classroom, had less absences and tardies and final grades rose by 4.5 percent.

However, some students, such as senior Caitlin Kulperger, consider themselves morning people. Kulperger has taken the zero period Leadership class throughout most of her time in high school, which starts at 7:05 a.m. According to Kulperger, there are few seniors in the Leadership class that have an issue with waking up early, but she admits there are days that are harder than others to get through.

“I don’t think it affects my morning as much, but weirdly enough, for me, it affects my afternoons more,” Kulperger said. “I get really, really tired in the afternoons. Coming home after my afternoon activities, it’s just hard to sit down and get homework done sometimes because I just feel so exhausted that staying awake is a little more difficult than it should be.”

Despite her preference for mornings, Kulperger thinks it would be nice to have everything, including zero period, start later to benefit student mental health and stability.

The drawbacks of a later start time

However, according to APA, logistical complications can arise due to later start times at school. School bus schedules would have to be rearranged, potentially leading to greater costs, congestion and road delays. Parents would be unable to rely on older children to care for younger children in the afternoons.

Though Meshel believes there could be some issues for parents having to find child care in the mornings, she does not think it would be as much as a problem for high school students.

“[In] high school, kids are more independent. They should be able to wake up and get to school on their own, especially if they go to a local high school and bike or walk to school… I guess the downside is that if they’re relying on a parent for a lift, and a parent works, it would be inconvenient for that parent,” Meshel said.

Another worry is that extracurricular activities could potentially interfere with school times in the afternoon and may have to be changed as well. However, Swoiskin believes that although school may have to end later as a result of a later start time, it would not affect the timing of her extracurriculars.

“I think that a half an hour more to sleep is more important than a half hour at the end of the [school day],” Swoiskin said.

Kulperger agrees that the later start time would be worth it, whether her extracurriculars are affected or not.

“I just think that it wouldn’t be as big of a problem if [school] was pushed back a little bit later because it would allow me to get home and still be awake enough [for homework],” Kulperger said. “I feel like it would allow me to sit down, get right to it and then get to bed at a reasonable time.”