When environmentalism meets affordability

May 29, 2019

Open space is 83 percent of land in Marin

Marin attracts people worldwide to come and enjoy all it has to offer. Being just across the Golden Gate Bridge, Marin draws in tourists to come see its view of the Bay, Redwood trees and expanse of open vistas. Though these spectacular natural features attract both visitors and long-term residents, legal provisions in place diminish the demand for land by preserving open space. Marin’s open space results in high property values, lack of affordable housing and prices of over $1 million for a single-family home. However, home owners aren’t just paying for a plot of land with a house on it. They are paying millions of dollars to own real estate with views of and proximity to some of the world’s most valuable features. This was made possible starting in the 1970s when residents began to understand the importance of the land around them and preserving it.

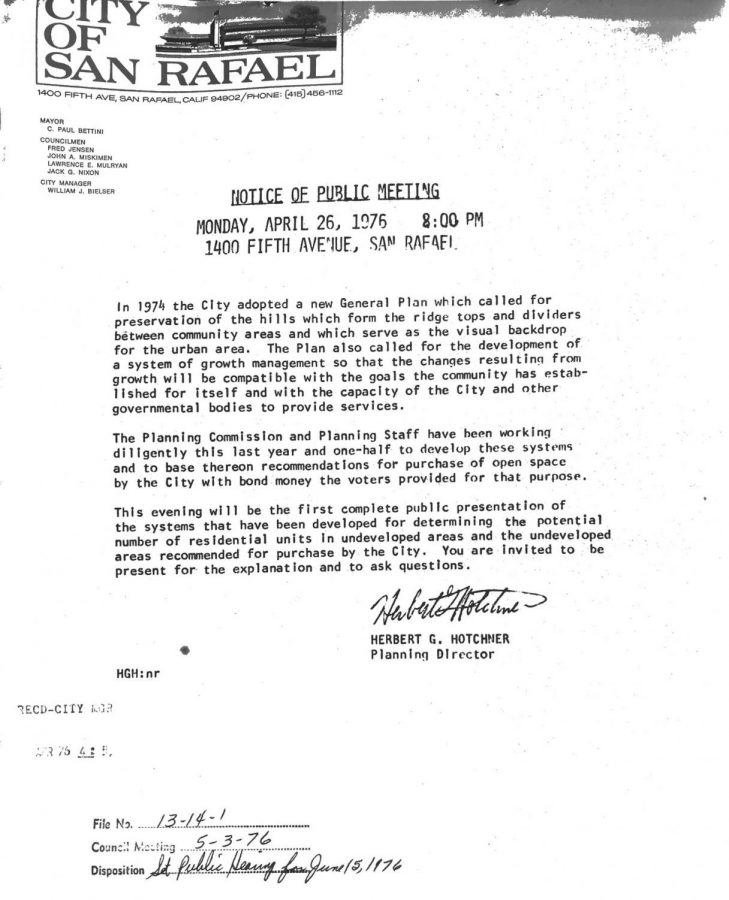

“In 1974, the City [of San Rafael] adopted a new General Plan which called for the preservation of the hills which form the ridgetops and dividers between community areas and which serves as a visual backdrop for the urban area.” This announcement was made in a San Rafael public meeting in 1976, when the adoption of open space began.

In the early 1970s, Marin policy makers began working to protect one of the most precious, and possibly overlooked, parts of the county. The open space of West Marin, according to the Marin County Parks Website, accounts for approximately 249 miles of road and trails, nearly 16,000 acres of lands and many thousands of additional acres, totaling 83 percent of land in Marin.

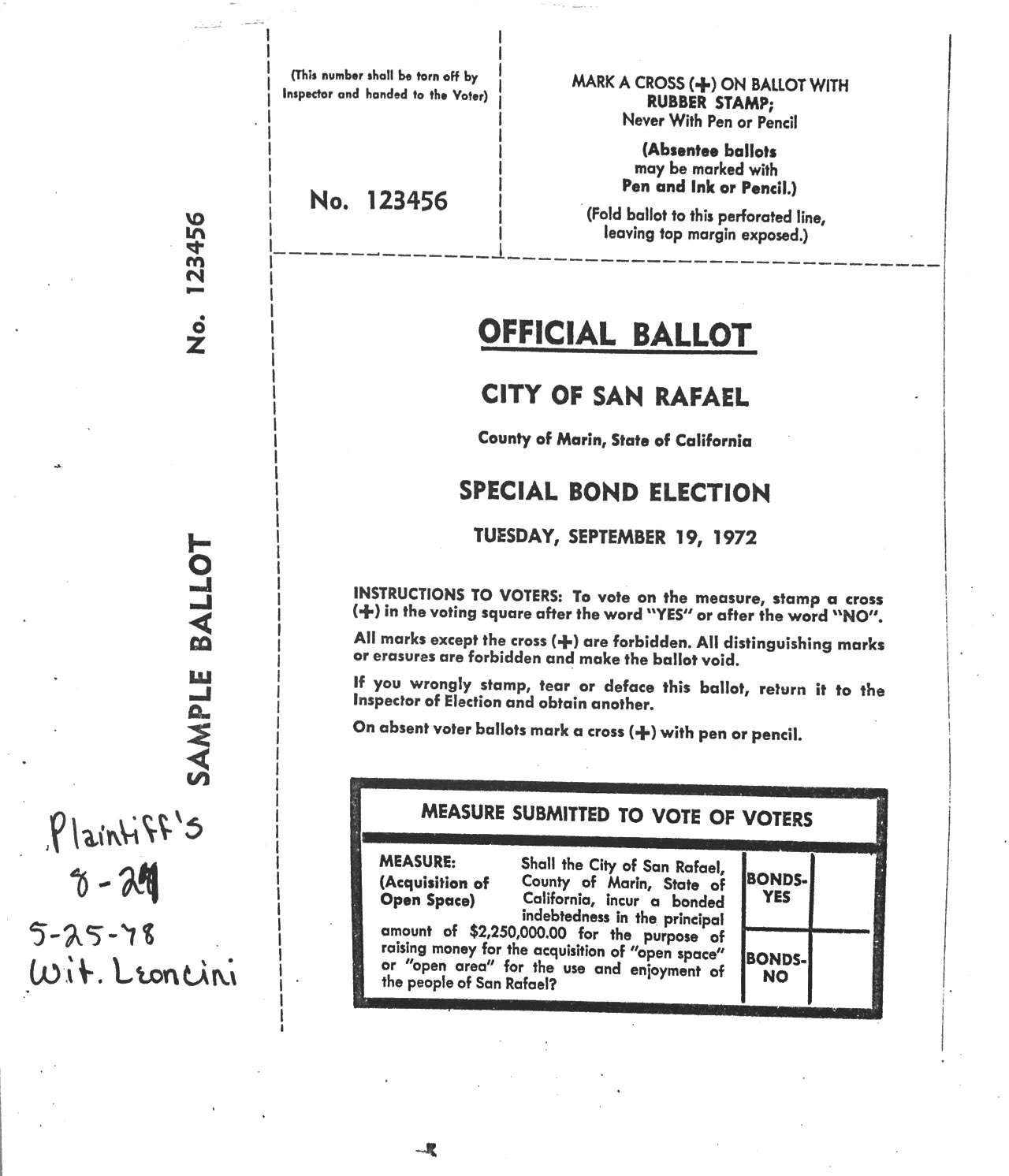

In the late ‘60s, the first movement to preserve valuable land in the Bay Area came about and eventually sparked an interest in protecting land all over the county. At this time, the federal government was looking for a private owner to purchase the land that occupied both Alcatraz and what now makes up the Marin Headlands. When word of this got out, more than 60 organizations came together to create a coalition called People for a Golden Gate National Recreation Area. At the same time, the National Park Service was in search of expanding outdoor public recreational areas. Then, in 1970 the first Earth Day was celebrated, bringing together both major political parties. President Richard Nixon signed a 1972 bill officially establishing the Golden Gate National Recreation area which since has grown to be over 750,000 acres of land. Later in 1972, Marin County voters passed a bill that created the Marin County Regional Park and Open Space district, which was later renamed as Marin County Open Space District. The Marin Countywide Plan ensures that no development is constructed along the 25-mile stretch of land that borders the U.S. Route-101 from Sausalito out through Novato.

After a few years of work, these organizations were able to stop the proposed development of a second bridge to ease congestion on the Golden Gate Bridge, a freeway running through West Marin, a highway along the Pacific Coast and a city of 125,000 residents in Tomales Bay. Several acts were passed post-1972 that continued to protect Marin’s untouched land. This set in motion the changes Marin was about to experience. Around the same period, in 1969, a law was passed that required every county in California to have a ‘general plan’ that includes a housing element. Part of this law mandates in the housing portion of the plan, each state must acknowledge affordable housing. Under this law, the government recognizes that requiring affordable housing means that there needs to be an adequate amount of land available to build upon. Plan Bay Area (PBA) coordinates land use and transportation policies, projects and public investment to stay consistent with the Marin Countywide Plan that protects the much-fought-for open space.

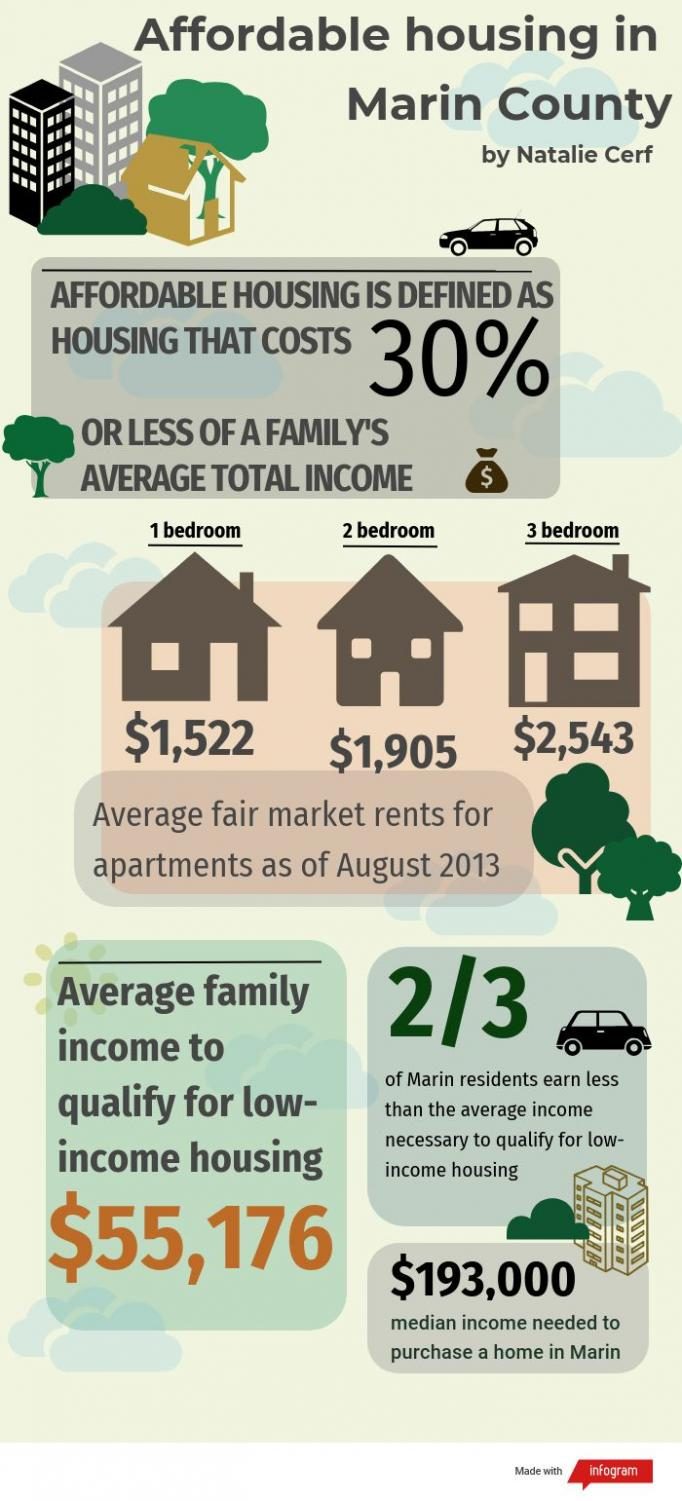

The affordable housing that the state requires counties to address, according to marincounty.org, is defined as housing that costs 30 percent or less of the family’s total income. As of August 2013, fair market rents were considered $1,522 for a one bedroom apartment, $1,905 for a two bedroom and $2,543 for a three bedroom. Two-thirds of Marin residents earn less than $55,176, the annual income necessary to qualify for low-income housing. Furthermore, the median average annual income required to be able to purchase a Marin County home is $193,000—more than half of Marin residents don’t make even half that amount.

Marin’s open space and its accompanying lack of low income housing are dependent on each other. When open space increases it means there is less land available to build upon, creating a subsequential void of affordable housing. According to the same 2013 report from marincounty.org, Marin’s ‘high-density’ population would be considered low-density elsewhere in the region’s urban areas. The 83 percent of land that is designated open space and agriculture creates an artificially high lack of construction-ready land, which has resulted in the inability to develop the necessary housing that would be able to support the majority of Marin’s residents.

When environmentalism collides with affordability

To what extent is MALT preventing more housing from being built?

Marin County residents entrust different organizations to protect the land that was promised to be preserved almost 60 years ago. Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT)—a nonprofit that works to permanently protect working farms in Marin County by purchasing agricultural conservation easements on the farmland—is one of those organizations. MALT is one of the leading operations that works to maintain the laws passed in the 1970s requiring protection of Marin’s open space. They work with landowners by making agreements that legally prohibit any non-agricultural use of the land. These agreements remain in effect even if the owner of the land changes.

In the 1960s, MALT was founded when Ellen Straus and Phyllis Faber, a rancher and an environmentalist, came together. Ranchers and environmentalists were thought to be working against each other at the time, as ranchers tend to want to use the land for all its worth and environmentalists work to preserve that land. However, when they became aware of the plans of coastal development, which included the 125,000-resident city along Tomales Bay and saw a need for land security at that time. Straus and Faber created an organization that ensures land protection, the first of its kind in all of America.”

In the 1960s, MALT was founded when Ellen Straus and Phyllis Faber, a rancher and an environmentalist, came together. Ranchers and environmentalists were thought to be working against each other at the time, as ranchers tend to want to use the land for all its worth and environmentalists work to preserve that land. However, when they became aware of the plans of coastal development, which included the 125,000-resident city along Tomales Bay and saw a need for land security at that time. Straus and Faber created an organization that ensures land protection, the first of its kind in all of America.”

MALT aids their partners in order to maintain the valuable open space as well-kept as possible. This includes a stewardship program that maintains and enhances the land’s economical value. According to Jonathan Wachter, MALT’s conservation project planner, the Stewardship Assistance Program helps farmers pay to implement more conservationally friendly aspects onto their farms.

“If a ranch has a need that is benefiting the environment, soil quality or water quality, then MALT can come in and help pay for those projects. It’s a really powerful program. It’s donor-supported so Marin residents and beyond are supporting this program,” Wachter said.

However, MALT wasn’t founded to support only ranchers. Their efforts work to enhance the living conditions of homeowners all over Marin, not just those living and working directly on farms, according to Wachter.

“MALT is protecting agriculture and open space in the county. MALT was founded to prevent large scale development in these agricultural areas. In that respect, it is preserving the environmental and aesthetic value for you, as a resident in Marin, of these areas that are in your ‘backyard,’” Wachter said.

Nevertheless, aesthetics may not always trump the importance of the availability of housing. Wachter acknowledges that MALT’s efforts may result in unintended collateral damage on housing availability or lack thereof.

“[There] is a bit of a tension. Because housing is such a shortage, there is so much need for affordable housing. To what extent is MALT preventing more housing from being built? It’s a tough question,” Wachter said. “As soon as you protect any natural land, in a way you are restricting something [else].”

Balancing preserving land and providing affordable housing

The City of San Rafael has specifically emphasized the importance of open space in its community. Paul Jensen, Community Development Department Director for the city of San Rafael, has worked for the city as director since 2008 and previously also worked there as a planner in the 1980s.

“There’s always been a passion by the people in this country to preserve land for open space. We’ve actually done a really, really good job,” Jensen said. “Every city and town in the state of California has to have a master plan or a general plan.”

In the 1963 general plan for the City of San Rafael, the goals of the community were focused on encouraging urban sprawl. There was emphasis on getting people to move into the suburbs and to build in the residential areas, according to Jensen. Jensen also explained that there were plans to fill in the San Francisco Bay all along Highway 101, Lucas Valley Road, Freitas Parkway, Terra Linda and downtown San Rafael and make a additional Bayfront freeway.

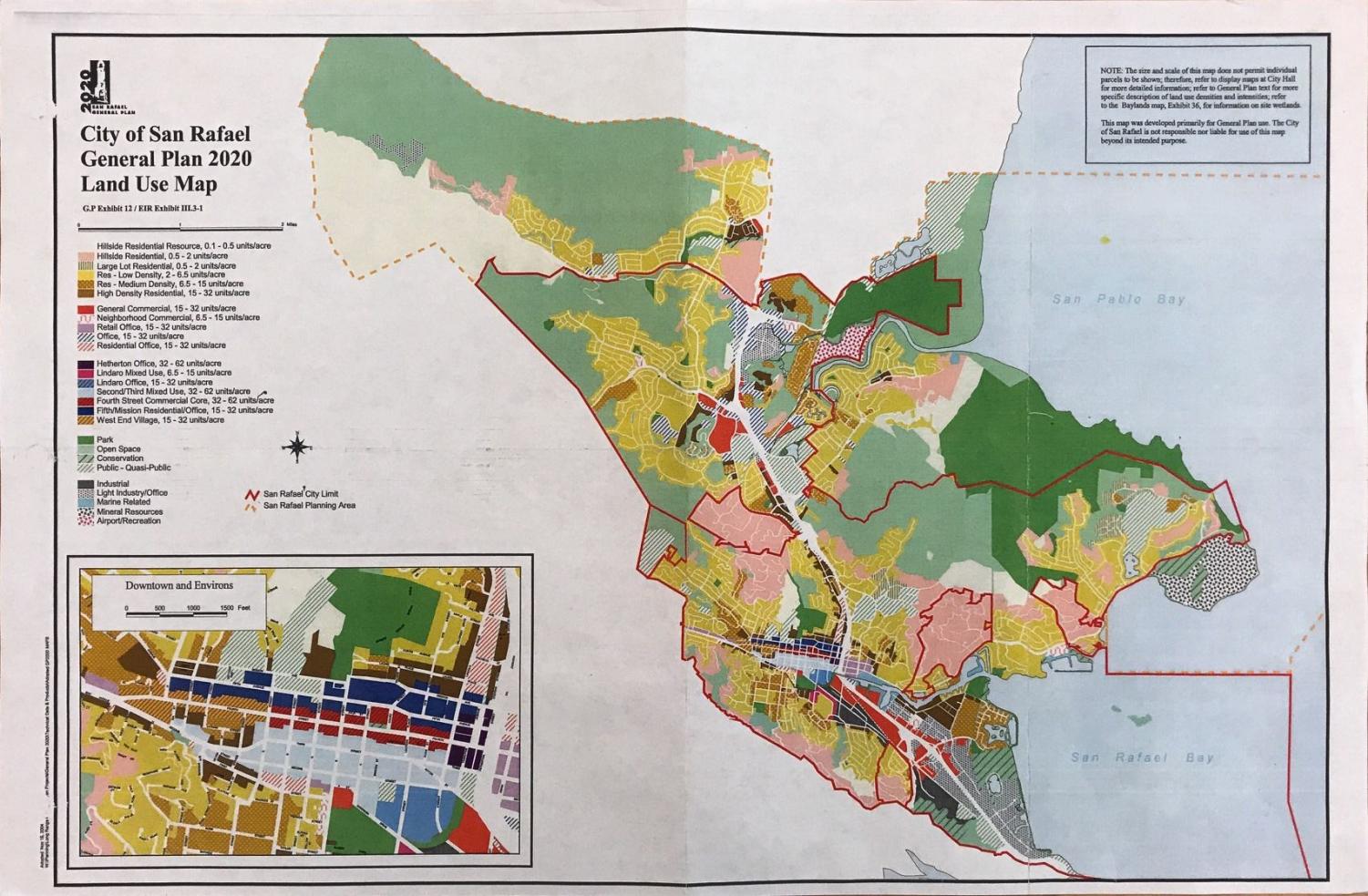

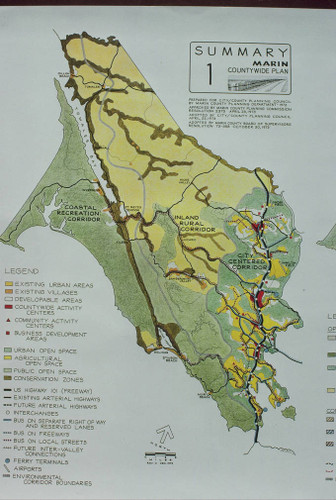

“Fast forward after 1973, everyone wanted to save the Bay and save open space,” Jensen said. “What happened was the county of Marin adopted the Marin Countywide Plan of 1972 and it put Marin County into three different zones: the Bayfront area where highway 101 is, the city center corridor where all land development was to be concentrated and the inland rural corridor. They took all of the property zoning for this area and made it agriculture only, so it could not be subdivided, and preserved this area for ‘ag’ land and open space. Then there was the coastal area which is called coastal recreation, most of which is GGNRA (Golden Gate Recreation Area). This was the first generation of protecting open space for ag land and for recreational use.”

Two years later, in 1975, the City of San Rafael followed suit and adopted their own general plan that worked to protect open space specifically in their city. Even though San Rafael doesn’t have any agricultural land, there is a lot of open space to be preserved. Even more steps were pursued in 1986 when citizens voted in a bond that taxed themselves and provided money for the city to purchase open space that was at the time currently owned by developers. The bond brought in $250,000 for open space acquisition.

“If you go to Northgate Mall and look at all the open space around it, that was all purchased with [bond money] and money from the city,” Jensen said. “This money has gone a long way by […] securing 3,285 acres of open space within the city limits and 7,300 acres within the planning area, the area around the city that is outside the city limits.”

As a result of the combined more than 10,000 acres of preserved open space in and around San Rafael, the land to the size of the population ratio is greater than most cities of comparable size.

“San Rafael covers a huge geographic area for the population that we have. Our population is about 60,000 but the geographic area is far larger than most other cities that have a population of 60,000 and a lot of it is because of the huge area that is open space,” Jensen said.

The land that the City of San Rafael acquired has served the city in many beneficial ways since the ‘60s and ‘70s when it became dedicated as open space. According to Jensen, a myriad of advantages to land preservation have surfaced.

“The open space has accomplished environmental protection, public access for recreation, visual backdrop,” Jensen said. “We are known nationally as this county that has beautiful conditions because we went through the extra step of preserving these areas from development. We are a draw in the Bay Area for people to come here, to cycle and to hike.”

Hand-in-hand with recreational advantages comes increased property value in Marin, and the subsequential desire to keep the population count low. According to The Bay Area Market Report done in 2018 on Marin County home prices, the median price of a home in central San Rafael is approximately $1,350,000. Jensen connected the abundance of open space to higher property value.

“I think it’s kept property value high. It’s a part of the quality of life that you have all this open space and ‘ag’ land in your backyard. It’s a benefit to your property value,” Jensen said.

High property values benefit some residents but they also restrict others, according to Jensen. Low-income individuals and families feel the effect of the county’s open space in a more adverse way.

“We did a good job of preserving all this land area, but what we did was we eliminated some areas of opportunity that could have been used for housing,” Jensen said.“Now we are essentially built out in our community. We have all of our built neighborhoods and our downtowns and then everything else is open space that you can’t touch. So we have to look within what we already have built to try to find areas for building the type of housing for the people who are having to live somewhere else.”

According to Jensen, had the open space been built upon, it wouldn’t create housing for low-income families, rather it would be more hillside homes, which are usually expensive as well.

There are possible solutions that could ease how impacted Marin has become by concentrated density levels. Jensen notices vertical vacancy in much of the buildings around the county.

“We are looking at places like downtown where we may be able to go up. Maybe that’s getting a little more metropolitan, but we’re kind of forced to do that to find places where we can put housing that is possibly affordable for people who are having to drive or take the bus from elsewhere because they can’t afford to live here,” Jensen said.

Jensen also knows the difficulty that comes with trying to preserve land while at the same time trying to provide available and affordable housing.

“It’s a two-edged sword. We’ve protected all this wonderful open space, we’ve protected the environment, we’ve created a recreation resource but we’ve forfeited some areas that could have been for housing for people who don’t [currently] live here,” Jensen said.

It feels like we’ve done one side of the deal

Affordable housing in Marin is rare, according to Leelee Thomas, the planning manager with the housing and federal grant division for the county of Marin. Thomas attributes the lack of housing to particular aspects of the county’s demographics.

“There’s a number of indicators. One is that most of the people who work in this county don’t live here. Over 60 percent of the folks that live in this county are commuting in, and they tend to be lower paid and more diverse than Marin’s population as a whole,” Thomas said. “Another is how high our rents are and how low our vacancy rates are, as well as how high the median housing cost is.”

This lack of housing available to families and individuals who don’t make enough money to buy into Marin’s housing market has a large effect on the community as a whole, according to Thomas. The people who work in Marin but have long commutes to get here aren’t able to participate in the community or economy as much, according to Thomas.

“Some of the impacts, in addition to traffic, are that those folks are not part of the community so they clear out and are not spending their dollars here. If you look at the county, the employees who live here are able to be involved with their community and if they are having to drive an hour or more, then they are not able to do that,” Thomas said.

People who have hopes of moving into Marin face the issue brought on by the lack of affordable housing as well. They have limited options of where they can buy or rent and it makes housing only available to the wealthiest, according to Thomas.

People who have hopes of moving into Marin face the issue brought on by the lack of affordable housing as well. They have limited options of where they can buy or rent and it makes housing only available to the wealthiest, according to Thomas.

“It limits who [is] going to live here. [Marin is] becoming more and more of an affluent-only community so we just don’t have diversity in income, as well as racial and ethnic diversity. Marin is the least diverse county in the Bay Area,” Thomas said. “We just have expensive single-family housing homes. We don’t have condos or apartments so that people can live at different affordability levels.”

While the amount of open space in the county affects the amount of available housing in the long run, it is not something that can be easily changed. According to Thomas, when it was determined that land would be made undevelopable, the county knew that meant they would have to compromise and build housing elsewhere.

“When the county decided that they were going to preserve that land […], the idea was that in exchange for that they were going to put more housing along the 101, along the freeway. We were going to build to some more dense housing, higher housing,” Thomas said. “There’s been a lot of community opposition to doing that. Unfortunately it feels like we’ve done one side of the deal, of making sure we’ve done a good job of protecting our open space but we haven’t done such a good job of building higher density housing so that only choice isn’t just a single family house.”

More housing can also be found by converting currently run-down buildings throughout Marin into livable homes and surrounding communities. Thomas sees potential in older commercial buildings that are currently underutilized.

“If we could develop those [buildings] and put housing above, a couple stories above, and then put retail or commercial space on the bottom, it would help support [the communities] and make them more vibrant. People want to have coffee shops and little markets in their community that they can walk to. You’d have more population and more people who could work in those shops and live locally that help support them,” Thomas said.

Nevertheless, some of the stigma around building high density housing in Marin that emerged when open space was first being proposed, remains today. According to Thomas, in order to be able to welcome a more diverse group of people into Marin while maintaining the open space that gives current residents high property values, people need to be willing to compromise and allow for the introduction of higher density housing.

“[Current residents need to be] open to developing a little higher density. People hear high density and they get a little nervous about it. People think they we’re going to turn into San Francisco, […] but nobody is proposing that,” Thomas said. “If you look at some of the older downtowns like Larkspur and Fairfax and San Anselmo, there are stores on the bottom and one story apartments up above. If we did that with maybe two stories above them, that could be a significant amount.”