Ten miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge with perfectly temperate weather, beautiful landscapes and an economy on the rise, Marin appears to be the idyllic place to live. However, the workforce of educators that enhance Marin’s desirability often lack the privilege to enjoy it. Oftentimes, Bay Area teachers can only appreciate it from nine to five, after which they must commute back to their more affordable homes outside of the county in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

Redwood AP Economics teacher Paul Ippolito is well-versed in Bay Area housing trends, especially those that affect him as an educator.

“You have two groups of teachers here, generally speaking,” Ippolito said. “[There are] teachers who bought a pretty small house a while ago and, given the pretty high salaries at Redwood High School, if you bought your house a long time ago, you can live in Marin and be okay … But at today’s prices, there’s no chance of a young teacher buying a house in Marin without help.”

Ippolito lives in Petaluma, and attributes his ability to live there solely to his previous job on Wall Street.

“I can only live a nice economic life because I brought my money from New York. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be here,” Ippolito said.

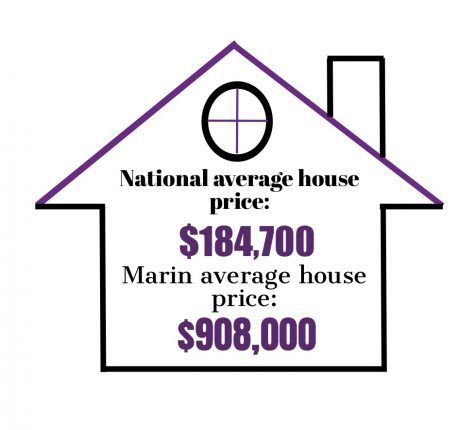

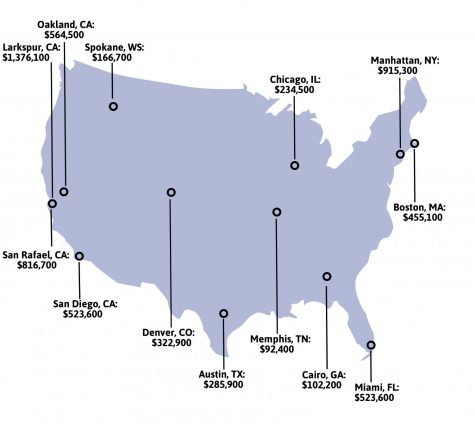

According to Transparent California, a website containing teacher salaries for districts across the state, the starting annual wage at Redwood for less experienced teachers often starts at $60,000 and can extend upwards of $100,000. The average salary for teachers around the rest of the country often levels off at $60,000. However, with a median home price of $908,800 in Marin according to community ranking website Niche, Marin’s higher wages barely make a dent.

Redwood graphic design teacher Nicole Mortham understands this struggle all too well as the majority of housing available in Marin well exceeds her budget. Mortham moved from Sacramento, where she worked at her local school district without any financial issues.

“In Sacramento, I was able to live comfortably. I had a three-bedroom, one-bath house that I owned by myself and then when I chose to move to Marin, at first I was very excited because it was actually a pretty significant pay increase but when it came to the comparison of living expenses, it wasn’t enough to live,” Mortham said. “I went from being in Sacramento, owning a three-bedroom house to living in an apartment in San Francisco with four roommates … And that costs about the same as my [current] mortgage.”

Mortham says her five years spent teaching in the district along with taking on more classes has helped her to sustain her current lifestyle in Fairfax. However, her housing situation is still not optimal for her.

“I’m much more comfortable now that I’m much farther over and down on the payscale, but I still spend half of my paycheck on my mortgage,” Mortham said.

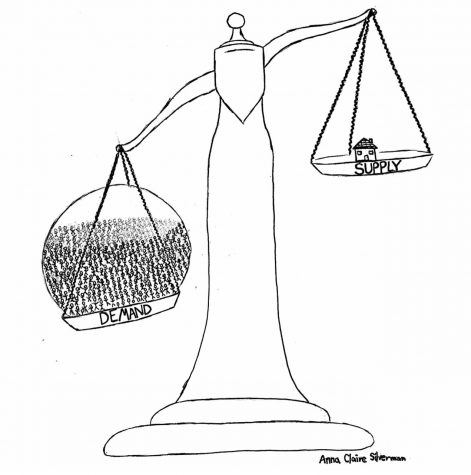

Marin’s housing crisis is due to the lack of housing paired with the attraction of living in the area, raising prices as the number of homes on the market falls. And, according to Robert Eyler, an economics professor at Sonoma State University, that number will continue to decrease due to demand not being met by supply.

“With a thousand people who want to live in a hundred [homes], prices are going to rise,” Eyler said.

The issue of supply and demand is one very familiar to the Bay Area. According to the Wall Street Journal, the number of jobs in California increased by three million in the last decade. In spite of this, the number of new housing permits issued fell to a quantity of 635,000, creating an abundance of workers but a lack of places to house them. This leads to the need to buy a home outside of the county and commute in daily, a lifestyle common among Redwood teachers.

“I know more teachers that live in cities 45 minutes to an hour and a half away than I know that live in and around Marin,” Mortham said.

William Carney, president of Sustainable San Rafael, works to promote practices of economic and environmental sustainability. One of the main issues they prioritize is housing affordability for the general public.

“We are, locally and regionally, in a housing crisis and particularly for housing that is affordable at a wide range of income levels. That has a very deleterious effect on the economic and human community because it means that we’re losing diversity in our community widely,” Carney said. “Using the ecological model, we don’t believe that systems survive very long or sustain themselves into the future without diversity.”

The cost of living in the Bay Area is a pressing issue without a clear solution, and its effects upon the community are already evident. Sustainable Marin is one of the organizations pushing for lower-cost housing, but its mission is being derailed by the direction of the economy. With prices expected to continue rising, affordable housing is not something that is necessarily in Marin’s future.

Rachel Percival, a realtor at Vanguard Properties, attests to the county’s sustainability but notices issues growing beneath Marin’s façade of wealth.

“They can’t build enough new houses to meet the demand that would be required … I think it’s always going to be a case of demand outstripping supply,” Percival said. “It’s just basic economics that the house prices are going to stay high.”

According to Carney, this means Marin will continue to drive out any semblance of a local workforce, something that is vital to sustainability and diversity within a community.

Diversity is necessary for the natural world, but its absence in modern society has an equally detrimental effect; declining representation of people other than those who can afford to live in Marin significantly affects the county’s cultural and economic environment.

Economic sustainability depends on the ratio of supply to demand and whether they are balanced enough to enable further economic growth. In Marin, the demand to work in the county is almost as high as the demand to live in it, and paired with employer desirability, this creates a very stable economy. However, its high appeal raises prices and raises the question of for whom is Marin actually sustainable.

In Marin, the economy is continuing to grow, but the diversity of the population and its culture are being lost in its wake as more and more are driven out.

“The increase in pay that the district offers, while I’m very grateful for it, doesn’t keep up with the cost of living in the area,” Mortham said. “Cost of living and salary make a huge impact on where I’m willing to work because I want to be able to spend money on things like trips and activities, and if all of my money is constantly just going to a space to stay it’s not sustainable and it’s not enjoyable. Although Marin has so much to offer, if you don’t have any money to go out andenjoy it, what’s the point?”

Economists agree that the only way to lower housing costs in Marin is to build more apartment complexes, increasing the number of living spaces and decreasing the demand. However, many current residents are opposed to this idea, partly due to the effect that it would have on local traffic. More housing guarantees more people, and more people guarantee more cars on the road. Inherently, this poses the question of where residents want their traffic: congesting the streets of Marin or congesting the freeways headed out of it. It also raises the question of how much the community actually cares about retaining their teachers.

One effort being made toward localizing educators is in the Mountain View Whisman school district in Santa Clara, which has median home prices of close to $1.5 million—even higher than those of Marin, according to their website. The district is commencing a $56 million project to construct a 144-unit extension on a current apartment complex for teacher rentals at $1,500 a month, which is over $1,300 less than the median one-bedroom rent for the county.

“Considering that living expenses are cited as the number one reason why we lose staff members, this partnership will ultimately benefit our students, families and the greater community,” superintendent Dr. Ayindé Rudolph said on the district website.

Developments like these throughout the Bay Area could help to stop the phenomenon of teachers not being able to afford housing local to schools, which will help to maintain teachers in the long run, something Redwood

struggles with.

“They might come here for a while if they’re willing to rent and live in a communal setting because it’s an exciting area, but they’re not going to stay here and raise kids. I don’t think it’s possible. I don’t think the school could pay enough to make that happen,” Ippolito said.

To lower Marin’s housing cost, mass building of apartment complexes in cheaper regions of the county is necessary. However, a partnership with the county and real estate developers similar to that of MountainView may help to retain a community of local teachers. This project has other future applications as well, such as the possibility for extension towards other lower-wage community workers.

In order to keep our teachers and rebuild a diverse community of local workers, its up to marin Marin to decide where to place their priorities: the residents or their educators.