The reality of methamphetamine use in San Francisco

March 24, 2019

Speed, ice, crank, chalk: meth. Over the past decade, the number of methamphetamine deaths has doubled in San Francisco, and as a result, Mayor London Breed and District 8 Supervisor Rafael Mandelman will co-chair a methamphetamine task force that will start meeting in the spring, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Methamphetamine (meth) is a synthetic stimulant drug that impacts the central nervous system, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Methamphetamine is either injected, snorted, inhaled or swallowed and causes the dopamine levels in the brain to increase rapidly, which can cause addiction. This addiction often leads to an overdose death, typically occurring from either a brain hemorrhage or sudden heart failure, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Although the methamphetamine epidemic is omnipresent in San Francisco, Marin has also fallen victim to drug addiction. Within the last 15 years, drug-related emergency room visits and deaths in Marin have more than tripled, according to the Marin Magazine.

Meth Epidemic

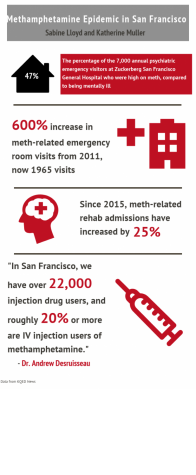

Over the course of eight years, there has been a 1,200 percent increase in meth-related emergency room visits in San Francisco, from about 150 visits in 2008 to almost 2,000 in 2016, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Marin County Public Health Officer Dr. Matthew Willis attributes this epidemic to the drug’s accessibility and addictive quality.

“Methamphetamine is, from a public health standpoint, a very concerning problem because the supply is difficult to control. It’s something that can be manufactured relatively easily in laboratories that can pop up in any community––it’s cheap, accessible, highly addictive and creates tremendous social harm,” Willis said.

San Francisco infectious disease physician Dr. Andrew Desruisseau also recognizes how drastic the problem is. He works in a clinic assisting many patients who are HIV positive and struggle with drug addiction in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, an area notorious for drug deals, according to Vice News. Roughly 20 percent or more of San Francisco’s 22,000 injection drug users use methamphetamine, according to Desruisseau.

The current primary concern regarding the use of methamphetamine is the absence of legitimate treatment. According to Willis, there is no established treatment for methamphetamine addiction like there is for opioid addiction, which can be treated with Naloxone, a medication used to block the effects of opioids.

Another key difficulty in addressing methamphetamine overdoses is the drug’s ambiguous symptoms.

“One of the difficulties is that people who use methamphetamine chronically can appear almost like a schizophrenic or psychotic for talking to themselves,” Desruisseau said.

Fighting the methamphetamine epidemic in San Francisco remains a problem, but is not the only area struggling with the drug epidemic. On a more local scope, Marin is also fighting a meth problem.

“Marin County kids actually misuse stimulants at higher rates than kids across the state, which says something about our community,” Willis said. “It’s an affluent community with a very high proportion of people with higher levels of educational attainment and goals for themselves and for their kids. That’s combined with higher rates of potentially performance-enhancing stimulants. [This puts] us at risk for higher rates of methamphetamine use.”

In Marin, the total number of drug poisonings has increased from 17 in 2015 to 37 in 2017, according to the California Department of Public Health and RxSafe Marin, a community coalition working to mitigate the dangers presented by prescription drug abuse.

Timi Leslie, Redwood parent and co-chair of RxSafe Marin, hopes to call attention to the problem in Marin and work as a community to combat it.

“I think it’s going to take all of us [to solve the drug problem]. It’s not just an individual problem, it’s not a family problem, it’s not a health system problem––it is a community problem,” Leslie said.

Solutions

One way to solve the problem using prevention is by providing people with opportunities to obtain housing and a job, according to Desruisseau.

“As one of my homeless patients always tells me, ‘Doing homelessness sober sucks.’ I understand that if you need to stay up all night and be really alert so people don’t steal all of your belongings, methamphetamine is a good option. So we need to improve people’s opportunities in life so we can help them overcome the addiction,” Desruisseau said.

Aside from providing more opportunities and resources, another solution stems from the origin of the issue, according to Willis.

“Why are people choosing to use illegal mind-altering substances in the first place?” Willis said. “Do we just accept that that is sort of an inborn characteristic of young people or people of a certain life stage where they will just experiment, or is there something that we can actually do that can affect that?”

However, Willis believes there are more direct approaches to solving the methamphetamine issue, such as working with law enforcement and opening safe injection facilities (SIFs), locations where people can inject pre-obtained drugs under supervision, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. Due to scientific evidence, Willis is in favor of safe injection facilities.

“If we’re taking a scientific approach, based on the public health evidence, safe injection sites are effective as a public health intervention for reducing the harm associated with injection drug use,” Willis said.

Desruisseau also believes safe injection facilities have the potential to solve the drug problem and has worked with the state government and legislature for many years to advocate for their operation. He even hopes to work with Gavin Newsom in the future after the last governor, Jerry Brown vetoed the bill.

“It’s cost effective and I’ve visited these facilities in Canada to have a look firsthand. We actually have a new bill that’s being introduced right now back in the legislature for approval,” Desruisseau said.

Support

According to Willis, support stems from understanding when the appropriate time is to offer help to individuals.

“A lot of people who are struggling with drug addiction aren’t ready for help, but there are moments in their lives when they are more ready for help than others and one of them is after they’ve had an overdose or some sort of bad event,” Willis said. “So we want to match our outreach to those windows of openness and that’s a strategy that we use with the opioids that we could also apply to meth, [which] is reaching out after a few days after an overdose event.”

On a high school level, Leslie believes that Wellness Centers serve as a tool to support students’ mental health and can be a safe space for those struggling with drug addiction or related problems.

“I’m a huge fan of our Wellness Center, and I think every school should have [one] or something [where] they can expand health and wellness,” Leslie said. “I think mental health is a huge issue and I think it plays a huge [part] in meth use.”

With students’ busy schedules, Leslie thinks that having a safe place readily available for students is an addition more schools should possess.

“You think about a typical high school schedule: for most of you, you’re in school from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. every day, especially if you’re involved with sports or the paper or Redwood TV. I know these things with [my daughter], you just don’t have time…So finding access points on campus is an area I hope to see happen in the next few years,” Leslie said.

Cera Arthur, Redwood’s Wellness Outreach Specialist, believes that the Wellness Center is able to provide for students with mental health illnesses and those experimenting with drugs and alcohol.

“[We are] making sure that the [Wellness Center] is approaching every student in a very non-judgemental and gentle way to make sure they feel comfortable coming,” Arthur said.

Arthur believes that many turn to the Wellness Center for support because of the resources it provides and its promise of confidentiality.

“I think a lot of people don’t feel comfortable talking to their family or friends; I think there’s a lot of shame around addiction. People fear consequences, and instead of punishing someone for using, you want to help and support them. I feel that people don’t think they will get that from home,” Arthur said. “It’s important for them to have a place here, and everything here is very confidential and I think that’s very important too.”