The persistence of segregation despite the decades

March 29, 2019

Some of the most dramatic examples of stark racial segregation stem from our educational system. There’s Ruby Bridges entering the steps to her new all-white elementary school or the Little Rock Nine, the black students who were physically barricaded from entering their new high school by the Arkansas National Guard. Whatever imagery is derived from segregation, it is usually a concept of the past. However, segregation is more prevalent and common in the modern day than it might seem on the surface, and it even occurs quite close to home.

David Minhondo, a history teacher at Redwood and administrator of the Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) club on campus, is adamant that segregation in schools should not be overlooked in the modern age.

“We are actually, as schools in America, more segregated now than we were before Brown v. Board of Education,” Minhondo said.

A study done by the University of California Los Angeles’s Civil Rights Project supports Minhondo’s claim; researchers have found that students are just as segregated today as they were in the 1960s.

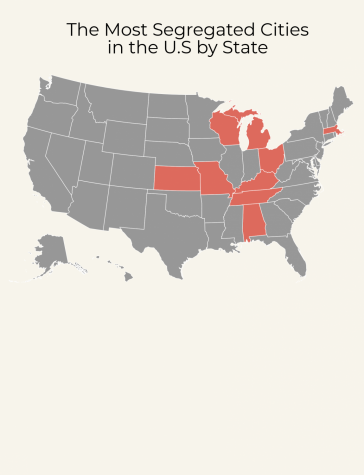

Racial division in education, geography and society has persisted despite legislative efforts to integrate. Most major cities remain greatly segregated––areas such as Southside Chicago, Brooklyn and Oakland have long maintained their status as majority African American neighborhoods. Although the Fair Housing Act of 1968 bans discrimination of all kinds regarding property sale and neighborhoods, the segregation in these communities goes much deeper: the school systems. In fact, the geographic segregation can be a direct result of school district zoning, according to University of Southern California Associate Sociology professor Ann Owens.

To test her theory, Owens overlaid school district boundaries across maps of the largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. Her study found that in 2010, 56 percent of residential segregation between white and minority families directly correlated with the perimeter of school districts in the area. Minhondo says that a history of racial inequality is to blame for these stark lines being drawn geographically.

“Schools become very insular; counties put up barriers that make it hard for people of color to move into them, and there are historic inequities that have caught up many people of color in the cycle of poverty,” Minhondo said.

In urban residential areas, many neighborhoods tend to be racially divided and less diverse. In cities like Detroit, the line can be drawn as dramatically as the city border, where black residents were practically barricaded from entering the suburbs as white families blocked the roadways with Christmas trees. Racial divides can also be only visible to locals, such as the Canal District in San Rafael.

Adam Gamoran, Sociology professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison, believes social tendencies are to blame.

“The segregation of American cities and suburbs is largely due to policies that enable segregation,” Gamoran said. “It occurs through a climate of hostility that makes it uncomfortable for people of different racial and ethnic groups to move into predominantly white neighborhoods. It’s done through white families departing residential areas if they become largely minority areas.”

The history of segregation and its relation to school districts has long been investigated by the courts of law with mixed responses. The Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954 was the first time that racial segregation in schools was addressed in a judicial setting. The justices agreed unanimously that the segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. However, in 1991, the Oklahoma City v. Dowell case was brought to the Supreme Court, with the Oklahoma City Board of Education arguing that it should not be required by the federal government to desegregate their schools. The case effectively ended required desegregation efforts, which have since been discontinued across the country, leading to a resulting atavism, a tendency to return to old customs of the past.

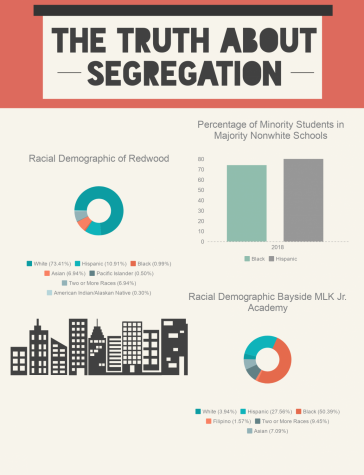

Despite holding seemingly progressive views, Marin is not exempt from the segregation that exists across the nation. In November of 2018, the Sausalito Marin City School District (SMCSD) was charged by the Attorney General’s office of violating anti-discrimination laws, specifically concerning the Bayside Martin Luther King Jr. Academy (BMLK), one of the two kindergarten through eighth-grade schools in the district.

Currently, an investigation headed by the Attorney General’s office is taking place to examine the extent of the charges. The ongoing case means that the board of trustees and superintendent of the district, along with other administrators, are unable to speak publicly on the litigation matters. According to Terena Mares, the superintendent of the SMCSD, the board’s silence is unavoidable although not ideal.

“I am very sympathetic and committed to sharing publicly what we can and when we can,” Mares said. “It’s in large part out of our hands, so the district at this point can only say that we are working diligently towards the time that the information can be shared.”

On an academic level, BMLK has also had lower test scores and comprehension levels than Willow Creek, their neighboring charter school with a white majority. According to Principal David Finnane of BMLK, the average eighth-grade student at BMLK is three and a half grade levels behind in math state standards, and two levels behind in English. Laura Cox, executive director of local community tutoring center Bridge the Gap College Prep, adds that there is also a discrepancy in available programs at BMLK compared to Willow Creek (WC) Charter.

“Funding controversy between the WC Charter School and the district school, BMLK, resulted in severe budget cuts at BMLK, resulting in the loss of a credentialed science, math and social studies teacher for three years in the middle school,” Cox said in an advisory council meeting.

Disagreement oversensitive racial topics is not new to Marin in light of the recent conflict regarding the name of the Dixie School District. Though the name has been in place since the district’s creation in 1864, many individuals and families are beginning to believe that it represents racist ideals reminiscent of the Civil War, while others argue it is meaningful to history.

Gamoran offers a brighter point of view for all schools struggling with racial segregation, saying that both residential and educational segregation, doesn’t have to be a permanent issue that we face.

“There are still things today that schools can do to advance diversity, starting with providing a welcoming environment to students of all racial and ethnic groups, continuing with abandoning practices of racial exclusion. School districts can also draw boundaries that are intentionally bringing students from different racial and ethnic groups together,” Gamoran said.

As it stands, however, most of Marin is almost entirely racially secular. According to KQED, white students make up 60 percent of all students in Marin, and 88 percent of those students attend a school that has a white majority. Minhondo believes that spreading awareness and having meaningful, understanding discussions will lead to better to integration and get the conversation flowing to instigate change.

“I think that there is a level of avoidance but it more has to do with unconsciousness, this idea that we don’t need to talk about it because it’s not a problem in our area or we don’t need to talk about it because race isn’t something we interact with on a daily basis,” Minhondo said. “Being white is the default. [Race] isn’t something that students don’t care about, it’s something that they don’t know to care about.”