Understanding the identity struggle of minority transfer students

June 11, 2018

Vietnamese senior Dana Nguyen picks up her remote control to turn on the television. Immediately, a cast of white actors fills her screen. She changes the channel; still, not a single minority is represented. Frustrated, she shuts off the TV and focuses her attention on the cover of the magazine next to her, which shows a Caucasian model and stories about white celebrities.

The lack of cultural and ethnic representation across social media and television platforms affects more people than just Nguyen. Over 25 percent of Redwood’s population was comprised of minorities in the 2016-2017 school year according to Redwood’s School Accountability Report Card. Similarly to Nguyen’s experience of underrepresentation in the media, other Redwood minority transfer students say they have trouble finding their identity in American society, in large part because of the white culture that surrounds them. For many students, adjusting to a new culture and language can be difficult, contributing to the identity struggle.

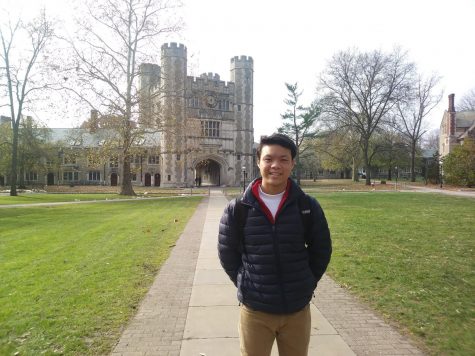

Nguyen came to Redwood in 2015 as a sophomore from Boston. She speaks Vietnamese and has been bilingual her whole life. While growing up, she often wanted to distance herself from her culture and heritage.

“My parents sent me to school on Sundays, when I was in first grade, with all of these other Vietnamese kids in Boston. I hated [Vietnamese school] so much that I didn’t try and I got held back for five years in a row,” Nguyen said.

She didn’t make an effort in Vietnamese school because she wanted to assimilate to American culture and the predominantly white population in America. This desire to assimilate has continued long after she discontinued Vietnamese school, and is especially strong at Redwood.

“I feel like my identity has been skewed and really detached. Growing up, it was hard because I wanted to be this white kid and I wanted to be like my other friends. I wanted to have nothing to do with my cultural identity,” Nguyen said. “That was a huge struggle for me growing up, feeling like I was different from these people. The fact that I was bilingual added something else since I just wanted to be a white kid who spoke English.”

As she grew up, she began to realize the importance of her cultural values and the way they shaped her as an individual.

“It was a huge identity struggle for me, but I’ve gotten to the point where I have started to embrace [my Vietnamese identity] and reclaim part of what I can. There’s some parts of me that I can’t reclaim back because of the environment that I grew up in and the world we live in today,” Nguyen said.

Even though Nguyen has become accepting of her heritage, transitioning to Redwood made it difficult to foster this new-found acceptance.

“I transfered [to Redwood] from a school in Boston, called Boston Latin Academy, [which was] one of the most diverse schools in the country. If I was still in that school environment with the mindset I have now I would be more connected to my culture,” Nguyen said. “At [Redwood] it’s hard because there aren’t that many Asians to surround myself with, especially Asians who are in tune with their cultural side and really embrace it.”

Senior Diego Kroell has also struggled with finding his identity. Originally from Guatemala, Kroell transferred to Redwood during his freshman year in 2015.

“I was a crazy kid, acting weird and telling everyone how I was feeling. That was a part of who I was. When I came here, people would always tell me to stop acting weird. I learned that I have to keep things to myself,” Kroell said.

When he came to Redwood, Kroell had a difficult time retaining who he was because he could not act the same way he had been accustomed to in Guatemala.

Nguyen and Kroell are not alone in this identity struggle. Roughly 70 percent of teenagers have experienced impostor syndrome, where they feel like they have a fraudulent identity, according to NBC News. The rate is even higher among minority transfer students, according to the American Psychological Association.

However, some students do not experience this identity crisis because their families want them to maintain a certain ethnic identity. This is the case for freshman Alec Sha, who moved to the United States from China in 2016, when he was in eighth grade.

“My family would not like it if I became Americanized because they value the Chinese tradition, and most of my family lives in China,” Sha said.

For students having a difficult time adjusting to Redwood, there are classes that can help with the transition, including the English Language Development class (ELD) and Spanish for Spanish Speakers class. The Spanish for Spanish Speakers teacher, Anna Alsina, believes that offering this class is extremely important to students, especially considering that 1.8 percent of Redwood students are not fluent in English.

“It’s valuable [for students] to use their native language in a school setting. They can use the language they speak at home in a different manner at school in a more academic way. They can expand [their language abilities] a little bit more by learning more academic vocabulary and being exposed to newspaper articles and all kinds of poetry,” Alsina said.

Offering these courses can help minority transfer students establish themselves and embrace their cultural background, according to Alsina.

“Having this class is a great start because it creates a sense of community. They can use their native language and talk about their culture in a comfortable setting. I think that is a great thing that Redwood does,” Alsina said.

Kroell is currently enrolled in the ELD class and believes that it builds a sense of community as well.

“I like the class because it makes you feel like you’re part of a group,” Kroell said. “We all have something in common.”

By offering these classes, Redwood is helping address the identity struggle that some minority transfer students experience, according to Kroell. There are also ways that other parts of the community can help as well, Nguyen believes.

In Nguyen’s opinion, people simply need to stand up for minorities who are struggling with their identities.

“When you see something that isn’t right, or microaggressive, or racist, then you should call it out. You can’t think that someone else will deal with it. When people talk about their problems and their problems are addressed, that’s when things get done,” Nguyen said.