The target is in sight. Tentatively looking over each shoulder before nearing the victim, timer in hand, the assassin closes in on the gap between defeat and victory. Suddenly, another player approaches, and without hesitation the assassin jumps head first into a nearby bush fearful for their life. The target, alert, swiftly turns around to scan the area for any nearby assassins. Before a complete analysis of their surroundings, the timer beeps loudly and victoriously; the target has been assassinated.

Although this may sound like a violent video game play-by-play, this is just another day at Drake High School.

The closing of the spring semester yields numerous academic tensions for many high school students. However, for the upperclassmen at Drake, the end of the school year generates a different stressor to occupy the final months: Assassin.

As the title suggests, each year Drake upperclassmen engage in a game of kill or be killed, named Assassin. The game, unaffiliated with Drake High School for liability purposes, is an ongoing tradition upheld by the upperclassmen at the school with the intention of enhancing school spirit and pride, according to the current game leaders, seniors Will Sibbett and Case Delst. This year, 68 teams, or 204 students, participated in the game, making up just above one quarter of the upperclassmen.

According to Sibbett, Assassin at its core is a game of strategy and caution.

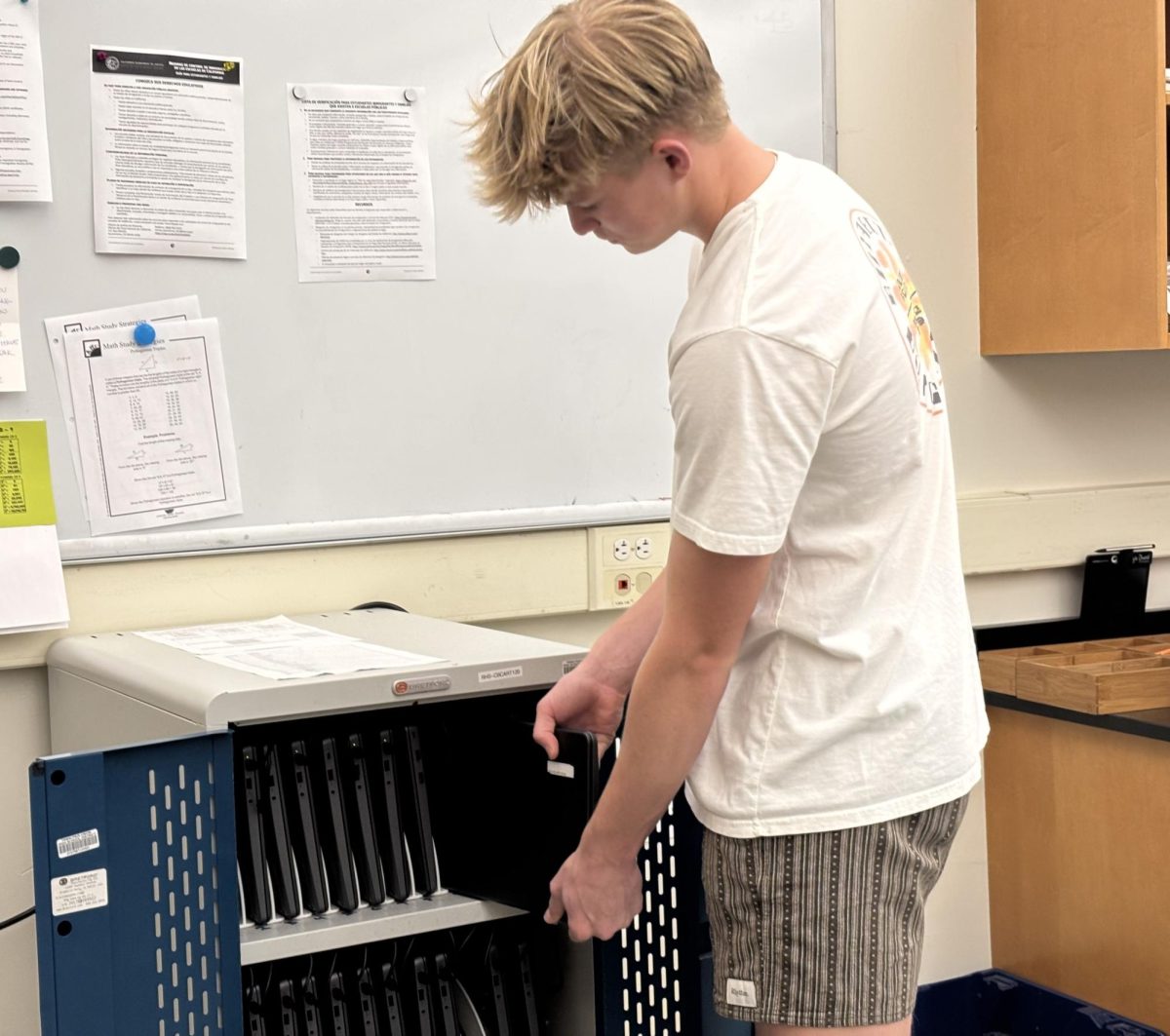

“The objective of the game is to be the last team standing. You have to kill other teams and not be killed by your assassin. You can kill people through water guns, water balloons, hoses, [rubber] snakes under desks and time bombs,” Sibbett said.

To kill a team using a “time bomb,” the team’s assassin must place a timer in a 100- foot radius of the team, and if the timer goes off without the target noticing, the team is assassinated. Additionally, to kill someone with a sneaky snake, a team will place a small rubber snake under the desk of another player, and if the target does not notice or remove the snake from under their desk, they will also be assassinated. ‘Poison,’ another assassination method, can kill another team through “poisoning” another player’s water or drink with salt. If the target drinks their ‘poison’ and reacts with a distasteful expression, the player is dead. Both captains noted that the various assassination methods require teams to be cautious and dedicated at all times.

“One player camped out in front of their target’s house for a couple days just sleeping in their car. That’s just one example of the level of intensity people put into this game,” Sibbett said.

According to the team leaders, each week is one “round” of Assassin where Sibbett and Delst assign each three-player team a target. Each team receives a “target,” or a team they must assassin, while simultaneously teams are being hunted by another team. In order to move onto the next round, each team must “assassinate” their target, using one of five methods, while avoiding being killed themselves.

Although the leadership positions to organize the game are usually awarded to the seniors who win the game their junior year, this year, Delst and Sibbett stepped in to fill the empty spots when they heard the winning juniors were uninterested in the leadership position.

According to Sibbett, the chance to lead the game was the ideal opportunity to stay involved with Assassin while not participating directly as a team member. As captains, Sibbett and Delst are responsible for organizing teams, sending out reminders, informing and updating administration, organizing “who kills who,” making rulings on disqualifications and arranging payment distribution among sorting out various conflicts. As leaders, Sibbett and Delst jointly receive around $600.

“Case had been given the opportunity to lead the game and since we are such close friends he asked if I wanted to help. I said sure, because then I wouldn’t have to play which is stressful as heck. And I would get some money and be a super spirited leader of our school,” Sibbett said.

According to Delst and Sibbett, the organization of the game itself has proved an extremely daunting task. Each week, both team leaders contribute seven hours of their time or more to make sure the game runs smoothly and all complications are worked out in a timely matter. As Assassin is a five-year running Drake tradition, the guidelines of the game itself had been previously outlined for them in a 13-page Google doc describing the game rules.

“[Assassin] goes from 7 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. almost every day. You always have to be on your phone making calls and settling arguments. At the end of this Will and I will have probably put in 30 to 40 hours each,” Delst said.

To participate, groups of three must enter a contribution of $45 per team, or $15 per person, to create a pool of money that is distributed once the game is finished after four to six weeks. At the end, the final team standing walks away with around $2,000 and the team leaders take a portion of the money themselves as reward for their dedication to the game’s success.

This year, as a result of increasing competitiveness surrounding the game, the remaining two senior teams split the money, with each player walking away with around $390. Although awarding the money to a single winning team would have increased the cash award per team member, both teams wanted to walk away with a portion of the money instead of an “all or nothing” result, according to the game leaders.

According to Delst, the money awarded to the final team provides incentive for players to take the game seriously while heightening competition for the final spot. In the past, according to Sibbett, teams have formulated creative ways to draw in their opponents in order to kill their targets and progress to the following rounds.

“My favorite part about the game is the creativity that people get to kill people. This year we had one team set up a fake Craigslist ad for a surfboard to lure their target in and kill them that way. Creativity like that is so funny and fun to watch,” Sibbett said.

Although the game is not officially connected with Drake, both team captains have made apparent efforts to inform the administration of the game’s progress. According to Drake Assistant Principal Chad Stuart, aside from necessary intervention in previous classroom disturbances, administration remains fairly equitable to the game itself.

“Administration is impartial. We know our students enjoy it. We like to see them having fun. That said, the name of the game and the fact it involves lookalike weapons is not something we support. We have made it clear that this is not a Drake-sanctioned game and it cannot occur on our campus,” Stuart said.

According to Stuart, although multiple behavioral issues occured when the game was first developed, he believes the team captains over the past two years have been effective in limiting classroom disruption by emphasising that possession of a water gun on campus will result in immediate disqualification among other on-campus limitations.

To restrict liability issues, Delst and Sibbett have disqualified teams who break the game rules in order to prevent further administration or police intervention. Although both team captains remain stringent on grounds of disqualification, issues with misconduct have been minimal as most teams try to stay in the game as long as possible.

“This year [Case and I] have had to disqualify a team for reckless driving. We usually try not to look over the team’s shoulder so much, but they were videoed passing nine stop signs and at least one red light. We looked at that and said, ‘This is illegal and could get our game compromised,’ which is why we disqualified them,” Sibbett said.

According to Sibbett and Delst, certain teams have gone to extensive limits to progress onto further rounds for a chance to win the large sum of money awarded to the final team. Sibbett has noticed this steadfast dedication prominently in some of the senior players.

“Most of the time it has been seniors that win because they are more dedicated to the game. For example in the past, some seniors even camped out on campus to make sure that they are in a safe zone all the time. Since the seniors are kind of more carefree they will blow off anything just to play the game,” Sibbett said.

Although the game itself requires extensive hours of commitment for both the game leaders and individual teams, Delst and Sibbett both believe the game will continue to serve as an essential tradition for the upperclassmen and an important symbol of Drake pride.

“We have senior ditch days, spirit days, walkouts, but I wouldn’t say there is a whole lot specific to Drake that we do other than Assassin,” Delst said. “Getting the rite of passage to play is a big honor and it was very exciting for me. Competing is one of the purest forms of bonding in my opinion. I think it is great for [the upperclassmen] to have an actual competition which doesn’t happen very much in high school As long as it is run correctly and fairly I think the game will continue to exist for a long time.”