Standing on the South Lawn, holding the sweet, delicate cookie, my mind conjures up images of my mother and me in a kitchen, cramped with three generations of Chinese women, folding succulent pork dumplings and gossiping in Mandarin—our native tongue. The Fortune Cookie, bearing a small piece of parchment commonly engraved with the words of Confucius, is a traditional and age-old sign of good luck and prosperity in China.

I’m kidding, of course. Unlike my mother, I don’t speak either Mandarin or Fujianese. I don’t eat meat. Many of my Chinese relatives live in places like New York, Alabama and England. And the brand of fortune cookie we know today was largely the invention of Japanese-Americans living on California’s coast, not some traditional, foreign practice.

Maybe it’s time to introduce myself.

My name is China. No, I wasn’t born there. Yes, I am half Chinese.

And yes, race has to do with it.

A few weeks ago, Redwood’s Leadership class decided to celebrate the Chinese New Year, advertising the sale of Panda Express at lunch. Later, on the morning of Feb. 14 and in a rather startling Valentine’s-Day-Chinese-New-Year fusion, I walked into school and was enthusiastically handed a fortune cookie while simultaneously wished a very happy Valentine’s Day.

Panda Express and fortune cookies did not serve as a celebration of Chinese New Year, but as a listless attempt to introduce something “exotic” into the everyday routine of school that ultimately promoted widespread cultural misunderstanding.

To the average reader, I’m not sure if my ethnicity qualifies me to comment on the use, and misuse, of minority culture. Or, if perhaps it simply paints me the archetype of a cavilling upper-middle class minority, demanding excessive recognition from a place of already healthy personal privilege. Maybe I sound like a young, technology-addicted “snowflake,” launching another self-righteous, politically correct crusade from behind a screen.

But, in an increasingly globalized society, it is only by speaking up about insensitivities that they can actually serve a greater purpose: to act as learning opportunities in the present and models of what to avoid in the future. Sending the message to the entire student body that egg rolls and broccoli beef are all you need to experience Chinese New Year is misleading… and, might I add, offensive.

Throughout my life, there have been moments when I’ve felt like Chinese culture was widely misunderstood. And it’s never more irritating than when I get to be a witness, up close and personal.

For example, few times have I been more painfully aware of my ethnicity than during a middle school field trip to Chinatown, a supposed supplement to our social studies unit on ancient Chinese history. The field trip didn’t feel like a celebration of culture. It felt like the manic dissection of a tourist attraction—one Americanized enough to be palatable, but still exotic enough to draw a crowd.

As we strode past pagoda-style buildings and open air vendors selling plastic Buddha figures, San Francisco keychains and license plate name tchotchkes, I was unimpressed with our tour. I felt that the commercialized nature of Chinatown, along with its complex immigrant background, wasn’t being distinguished from the traditional Chinese culture it seemed we were supposed to be observing. Take the New Year Parade: an NBC article released earlier this year was titled “A Chinatown tradition, San Francisco’s Chinese New Year Parade is ‘American like chop suey.’” The article cites the fact that the parade was at one point an attempt to improve relations with the rest of the city during WWII out of fears of encampment. Chinatown is largely the result of Chinese immigrants altering and commercializing their culture in an attempt to be accepted and make ends meet in a hostile city during an era of Chinese-only schools, housing discrimination and the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Somewhat paradoxically, after the tour it felt like my responsibility to remind my peers that, no, most Chinese dinner tables don’t feature turtle soup or puppy stir-fry. Or that, actually, fortune cookies originated in San Francisco, not China. (In the early 1990’s, the New York-based Wonton Food Company actually began selling the treats in China, advertised as “Genuine American Fortune Cookies.”)

The erroneous interpretation of culture is irritating on a small scale, but the real danger comes when this ignorance is sponsored by a dominant or representative group of people. Whether that be the leadership of a school, a workplace or simply a group of the racial majority, the result is large scale misunderstanding.

And while there is nothing wrong with cultural exchange—the conscientious and mutually-enriching process of sharing cultures that makes much of America diverse and inclusive—it can be more harmful than enlightening when botched.

Because of this, sharing cultures (especially not your own) comes with an incredible amount of responsibility.

When a dominant culture or group publicizes a narrative, whether or not accurate, it will be listened to. That, in many ways, is the essence of privilege. And if the privilege of one group is being utilized to tell the story of another group, regardless of good intentions, it is important to recognize the damage that can come from telling an incorrect or incomplete story.

Cultural exchange is not serving Panda Express on the South Lawn. It is not handing out fortune cookies and tactlessly meshing Chinese New Year with the overtly commercial holiday that is Valentine’s Day. It is not diluting an ancient celebration into trite and palatable components in order to squeeze it into a 40-minute lunch period.

The broader Lunar New Year celebration is the most important holiday in China as well as Korea, Vietnam, Singapore and a number of other countries.

During two weeks of celebration, many businesses close their doors, allowing people to travel to spend time with their families. Family is a central theme; the holiday allows different generations to connect and traditions to be passed down. For example, it’s taboo to give clocks as gifts but customary to give red envelopes (hóng bāo) containing money. It’s unlucky to clean during the celebration because it’s said that luck can be swept out of the house and it’s impolite to stick chopsticks upright in a bowl of rice because it’s reminiscent of incense at a funeral. During a holiday steeped in traditional values and driven by auspicious practices, telling the entire student body that the Americanized Chinese food of a multinational fast food chain is an appropriate way to celebrate a 5,000-year-old holiday condones widespread ignorance.

The Lunar New Year is a complex holiday. It is difficult to understand without cultural context. But if it is to be truly celebrated, a complete narrative must be told. Include the input of the voices being represented. Include the perhaps confusing practices. Include the archaic values.

Certainly as students, we aren’t perfect. But Redwood can do better.

Whether students are enjoying fortune cookies in San Francisco under the pretense that they represent Chinese culture or Panda Express under the pretense that it counts as a celebration of Chinese New Year, the fact is that if any form of a leadership body attempts to bring another culture into the mainstream in order to celebrate it, they should strive to get it right.

In a liberal pocket of liberal California, and in a school district that talks of acceptance and the celebration of diversity, I would hope Redwood’s Leadership could get it right.

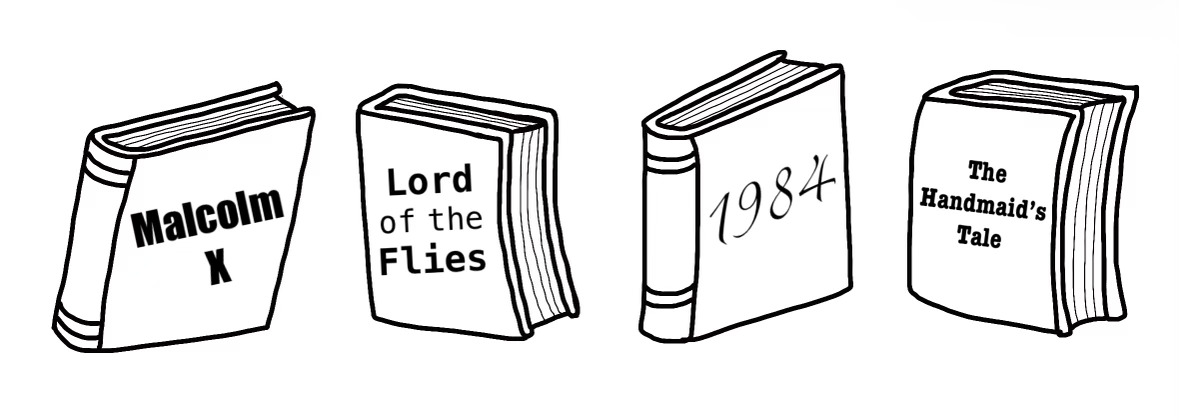

In an institution of learning that warns about the dangers of telling a single, stereotypical story, our leadership body has an obligation to get it right. Please, let this serve as a lesson, a future call to action against the institutionalized complacency of cultural ignorance.