The Tamalpais Union High School District (TUHSD) science curriculum will undergo significant changes starting this fall due to the new California-mandated implementation of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). The new standards will impact students’ science education requirements beginning with the class of 2022 and are already posing a challenge to Redwood science teachers.

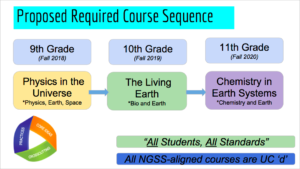

Redwood will begin implementing these standards in August 2018, when Integrated Science 1-2 will be replaced by a year-long Physics of the Universe course. In the following year, the 10th grade Integrated Science 3-4 course will be replaced by a new biology course, The Living Earth. Then, in August 2020, a new chemistry course, Chemistry in Earth Systems, will be offered for 11th grade students. The rest of Redwood’s science curriculum is expected to remain the same.

Multiple science teachers support the new research-based approach to teaching science, including AP Environmental Science and Sustainable Agriculture teacher Joe Stewart, Physiology and Honors Integrated Science teacher Todd Samet and Physics teacher David Nash.

“I’ve been teaching for 34 years and this change is potentially a game-changer in a positive way in terms of how science will get taught,” Samet said.

Samet believes that reducing the number of concepts taught allows for more depth learning in each area, which will enhance how well students understand science. Stewart said that the new science standards emphasize how science is taught and learned instead of focusing on content.

TUHSD is not alone in applying NGSS for K-12 students; 19 states have adopted the new standards. The updated science curriculum was made necessary by the tremendous scientific advances in biology, space exploration, artificial intelligence and robotics in the last 20 years, according to the NGSS website.

The last time science teaching standards were revamped was in 1996, when the National Science Education Standards were adopted. These standards emphasized content-dependent critical thinking skills over knowledge of disconnected facts.

TUHSD’s Senior Director of Curriculum and Instruction, Kim Stiffler, explained that a core concept of the new standards is that teaching of content is integrated with scientific and engineering practices.

TUHSD has facilitated the transition to the new standards by setting up a task force led by teachers, administrators and district office representatives to develop the sequence of the new courses as well as for the topics within each course. A group of four science teachers from Drake, Tam and Redwood are putting together most of the curriculum, according to Nash.

However, Nash explained that teachers are struggling with the transition. Biology and earth science concepts will be woven into the new curriculum but will not be the main focus as they were in the Integrated Science courses. As a result, not only do teachers need to learn the new standards, but they also have to develop new teaching plans and become recertified in different science subjects.

Approximately seven science teachers must become re-credentialed to teach the new courses, according to Stewart. To be able to legally teach the new classes, science teachers have to pass a qualifying exam at the state level. The teachers and Stiffler agree that the test is challenging.

“I’ve looked at the physics sample test they publish on the web, and it’s not easy,” Nash said.

Science teachers will need training to teach subjects they haven’t taught before, such as chemistry and engineering.

“If you’re a biology background teacher and you’ve been teaching Integrated Science—mostly a biology course—for 25 years here, you don’t know how to problem-solve in physics at a pretty high level,” Nash said.

The physics qualification test is not appropriately designed to measure the instructors’ abilities to teach the new science course, according to Nash, who compared the teacher’s test to an AP Physics test from 30 or 40 years ago. Because teachers must pass this exam, their focus could be diverted from preparing for the new course, he explained.

“The part that’s a shame is that if [the teacher is] going to teach this new course, isn’t getting ready to teach the new course the primary concern? Not trying to take a 1980s style AP test in physics?” Nash said.

To address the difficulty of the exam, TUHSD is providing professional development for teachers, which includes bringing in physics professors from College of Marin to run workshops and tutoring sessions. However, retraining is a time-consuming process.

According to Stewart, the teachers have been undergoing training for two hours once a month throughout the school year. Additionally, they were offered training for 10 full days during the past two summers. Stewart estimated that teachers have undergone approximately 180 hours of training in addition to the time they might put in on their own.

Another challenge in implementing the new standards is the increased costs caused by the hands-on engineering practices. Funding additional classroom projects and field trips may be difficult.

“The science department at Redwood has requested around $10,000 for materials at Redwood specifically,” Stewart said, although he anticipates that additional funding will be required.

Stewart explained that there is some district money allocated for these expenses, and the science department hopes that the Redwood Foundation will assist with funding too. However, the department is worried about funding, according to Nash.

Nash also expressed concern that there are no honors versions of these courses being planned. Integrated Science 3-4 has had an honors version offered at Redwood for at least 20 years.

While it’s likely that sophomores will be able to address this shortcoming by doubling up on their science courses, Nash feels that there should be an honors science option for students by 11th grade, such as a chemistry class based upon more sophisticated math concepts.

Like teachers, students will be impacted in various ways. The most significant change is that Redwood graduation requirements will become more onerous. Redwood students will now have to take three years of science to graduate as opposed to two years.

On the other hand, students will be able to earn University of California lab science “D” credit more quickly. It previously took two years of Integrated Science to earn one year of UC credit. If all three courses are approved, students will earn a year of UC credit for each year of the new science courses.

To date, only the new freshman course has earned University of California lab “D” science approval, according to Stewart. Approval has not yet been sought for the new 10th and 11th grade courses, but it is expected to occur over the next two years as course planning for each class is finalized.

![There are six lockers located in the gender-neutral bathroom in the small gym. “We really want [students] to have somewhere else [where] they feel safe and have a real changing [room],” Graydon said.](https://redwoodbark.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pcJSAwmgWmNzPSBmtkk8SO2goGbkm5e2TvgxGpTr-1200x800.jpg)