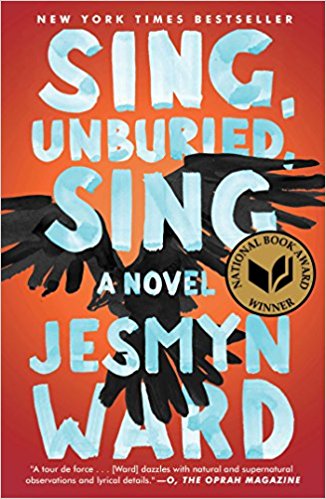

“The branches are full. They are full with ghosts, two or three, all the way up to the top, to the feathered leaves,” thinks Jojo, a biracial 13-year-old boy, standing in his grandparents’ yard. This image is emblematic of perhaps the most human aspect of the Jesmyn Ward novel, “Sing, Unburied, Sing:” that which haunts us.

The novel follows Jojo as he and his four-year-old sister, Kayla, embark on a mission with their drug-addicted Black mother, Leonie, to recover their White father, Michael, who is about to be released from Parchman, a Mississippi state penitentiary. Ward simultaneously delivers a heartbreakingly poignant portrayal of a fractured family, haunted by Leonie’s addiction—both to drugs and to her tumultuous relationship with Michael—and a fractured America, beset by the systematic racism woven so intricately and heavily into its history.

Set in Bois Sauvage (which translates from French to “Wild Wood”), a fictional town in Mississippi, “Sing, Unburied, Sing” alternates in perspective between Leonie and Jojo as they make the arduous trek upstate. Cramped, irritable and hot, this road trip is full of misadventures. From stopping so Leonie can buy and sell drugs to Jojo nearly getting shot by a police officer, it serves to juxtapose the literal proximity of Leonie and her children with the emotional chasm separating them.

This tension is amplified as the narrative passes back and forth between the two. Jojo rarely offers Leonie any sympathy, believing her to be, pretty accurately, selfish and reckless. He hardly acknowledges her as his mother, and the cynical insight with which he sees the world is a product of his disenchantment by Leonie’s missteps.

Through Leonie’s melancholy, brutally honest confessions, we can understand her shame and disappointment past what her teenage son can perceive. As the novel progresses, we learn that Leonie’s brother, Given, was killed by one of Michael’s cousins, and she has several conversations with him as an apparition—which she can only see when she’s high.

Ward paints a beautifully complex image of Leonie’s psyche: a woman who, at times, is jealous and even resentful of her children’s fierce bond, yet still craves their affection and tenderness, who understands the destructiveness of her negligent behavior yet routinely lets her responsibility fall victim to her addiction. Leonie has been trapped and dejected by grief and the racist culture characteristic to rural southern America that offers Black citizens neither opportunity nor justice, and has lived so restricted by oppression that it has become the defining quality of her life.

In one of the many ironies of the novel, as they return, Jojo begins to see Richie, an apparition of a child who was once incarcerated at Parchman. He tells Jojo of the horrific realities of Parchman.The stunning parallels between the prison and a plantation make Parchman an explicit parable of the American criminal justice system’s role in perpetuating racist control. This can is illustrated in Richie’s description of the prison, saying it felt like he was standing “in a field of endless rows of cotton [and] men bent and scuttling along like hermit crabs, bending and picking.” The history of Parchman—a successor to the convict lease system which, after the Civil War, disproportionately imprisoned black men—demonstrates both the hold that history has over the present, and the persistence of racial inequality in America.

Ward’s writing is beautiful in its lyricism, yet blunt and honest in its description of the ugly truths of the South and the hardships that threaten to overcome familial bond. Yet at points, Ward’s language becomes too flowery, and certain metaphors she uses begin to drag and feel misplaced. Especially prevalent in depictions of the scenery, the excessive flowerieness becomes tiring, and can be seen when Jojo says, “Eyes blink as the sun blazes and winks below the forest line so that the ghosts catch the color, reflect the red.” While picturesque, it slows the progression of the narrative. It also blurs the distinct tones between the two narrators and confuse their separate perspectives, sacrificing some of the plot development to the poeticism.

While reading this novel, the ghosts in it did not feel like fantastical superstitions: rather profound memories, ever-present, ever-ignored individuals. The restlessness of these spirits illuminate the lack of closure in American history—and the lack of acknowledgement of it—and remind us that there are still stories that beg to be told, and songs that beg to be sung.