Okay, I’ll admit it—I’m a complete and total art nerd. I geek out in museums; I take Art History; I slip obscure art jokes into daily conversation and I laugh a little too much at art memes. If I could, I’d visit museums for days, purely because there’s so much phenomenal art! Yes, I wasn’t always like this—who didn’t dread being dragged to galleries as a kid—but as I’ve matured (well, okay, maybe that’s not quite the word for it), I’ve been able to appreciate the vast multitude of human knowledge, achievement and creativity that is curated in museums around the world.

From the Legion of Honor field trips I took in elementary school to visiting the Musée D’Orsay on a family vacation and everything in between, my life has been chock full of ugly medieval babies, vivid abstract canvases and portraits of old important white men. I’m being facetious, but seriously, you name it, I’ve probably seen a version of it.

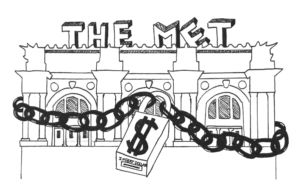

The Met, one of the largest and most prestigious institutions in the world, is ending its pay-as-you-wish policy this year, a unique and treasured program in place since 1970. From March 1 on, it will charge a mandatory $25 fee to out-of-state visitors.

Just as I grew up exploring galleries, I believe that museums should be accessible to all, regardless of one’s economic situation. Everyone should be able to experience these visual libraries, rich or poor, knowledgable or not about the works beyond the front doors.

It is understandable that the Met wants to raise revenue to keep themselves running. After all, shutting down a museum is exceedingly worse than charging a simple entrance fee. However, by burdening the general public with increasing revenue, the Met is discouraging out-of-state tourists from visiting. They are detering a whole population from cultural exploration and enrichment.

The Met is not alone in charging visitors. In fact, hundreds of museums across the country and around the world demand an entry fee. According to the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), arts and cultural production constitute 4.32 percent of the entire U.S. economy as a $704 billion industry.

Unfortunately, more than two-thirds of museums reported economic stress in 2012, according to the AAM. As of 2012, the average U.S. museum received just over 24 percent of operating revenue from government resources, a decline from the 38 percent in 1989, according to a 2012 pamphlet by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of International Information Programs.

Additionally, museums like the Met mainly sustain themselves on donations, endowments and wealthy patrons. Getting donors to back less glamorous projects such as admission revenue is a tough job. Many prefer to support more tangible projects. A recent example is the Met’s Koch Plaza, completed in 2014 and fully funded by Museum Trustee David H. Koch, who covered the $65 million bill. The money spent on this project would have covered admission income for almost a decade!

Patrons aren’t necessarily the answer to a museum’s upkeep problem, as they often want to showcase specific art pieces or put their names on fancy and sometimes superfluous ventures. Museums, like traditional libraries, should receive government funding to fulfill the costs of running such an institution, instead of relying on rich donors or admission fees.

Take England as a successful example. In December of 2001, they instituted a government policy to fund free admission to national museums. According to the U.K.’s National Museum Directors’ Council (NMDC), in 2010/2011 nearly 60 percent of visitors to the U.K. visit the free Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS)-sponsored museums. And, the visitor economy contributes £114 billion, or 8.2 percent of the U.K.’s GDP.

According to the New York Times, attendance of the Met has steeply increased in the last 13 years, from 4.7 million to seven million visitors. On the other hand, the proportion of visitors who pay the full “suggested” amount of $25 has declined from 63 percent to a mere 17 percent. Clearly, this is an issue, as the Met struggles to fund itself, especially when competing with the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim, among others.

However, the Met is focusing on the wrong side of the problem. A long-term solution would be to focus on marketing paying the “suggested” price. New York Times chief art critic Roberta Smith suggests that the Met form a humorous campaign urging those who can to pay the full price.

“So hire a really good design firm to formulate some kind of counter campaign. Like ‘If you’re wearing mink, or a bespoke suit, or if your entire outfit totals out at more than $3,500, think about dropping $25 to visit the greatest museum in the world. You’ll be helping others who can’t afford your wardrobe,’” Smith wrote.

I am not trying to diminish the fact that many museums offer student or youth discounts, including the newly-renovated SF Museum of Modern Art. Some museums also designate admission-free days, when anyone can enter without paying. In fact, I applaud these measures; I just don’t think they’re enough.

AAM states that museums are considered the most trustworthy source of information in America, higher than local papers, nonprofits researchers, the U.S. government or academic researchers and are considered to be a more reliable source of historical information than books, teachers or personal accounts. So why are we building a wall between the people and (in their eyes) the most credible sources in the country?

I want a young girl visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) in New York City from a small town to find her drive for painting because she couldn’t tear her eyes away from Claude Monet’s “The Water Lily Pond,” just as I did gazing up at Monet’s “Les Coquelicots” in the Musée D’Orsay. And if her family can’t afford to bring her face-to-face with that beautiful work of art, how will she discover that new pursuit?

The Met’s pay-as-you-wish legacy is being toppled by challenging economic times and a growing attitude that charging for museums is inescapable. I believe that it should be the opposite; the pay-as-you-wish policy is a universal and impressive principle that should be upheld and replicated across the globe, starting with our own country’s industry. No one should be denied access to something as vital as cultural history, knowledge and growth.