In a county such as Marin, known for its progressive and liberal character, it may be easy to believe that issues of racism and inequity barely exist here. The atmosphere in Marin leads its citizens to buy into the idea that everyone around them is successful, happy and looking out for the well-being of the others in the community. However, to believe in this concept of near perfection is to be ignorant of the fact that there is an underlying system of racism, racial inequity and socioeconomic inequality that permeates the walls of Marin, directly affecting the school system.

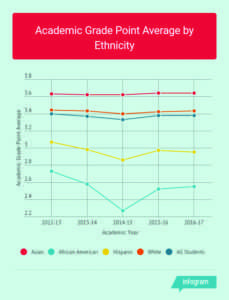

Across Marin, Latino and African American students, as well as students of lower socioeconomic backgrounds, perform at staggeringly lower levels in school than those of their White, Asian and wealthy counterparts. According to the T.U.H.S.D. school district’s data, in the 2016-2017 academic year, the average GPA of African American students at Redwood was 2.55, while Asian students’ average was 3.64 and White students’ average was 3.43.

Wendy Pacheco, the coordinator at the Youth Leadership Institute (YLI), an organization that promotes a partnership between Marin adults and youth that work to address social, educational and political issues in the community, states there are subtle racial inequities in schools that deeply affect minority students. Among those injustices is the lack of ethnically diverse teachers and counselors at schools.

“Research suggests that if you have folks who reflect your experiences in positions of power, then that is more likely to influence how you feel about yourself and what you feel your trajectory can be in securing a position of power, whatever that may look like,” Pacheco said.

Pacheco explained how this can translate into high school, where students are looking up to their teachers as authority figures.

“In a school setting, the teacher is that position of power. They are the ones that stand in front of the classroom and hold the authority of that space,” Pacheco said.

This lack of diversity can lead to a situation where minority students do not feel supported by their school community because few individuals in those positions of power share similar life experiences, according to Pacheco. This can result in difficult situations in which staff have issues understanding where the root causes of the inequity lies, and what they need to do to provide for their minority students in order for them to share the same potential for success as the majority of their peers.

“Part of that is not just that there are not as many teachers of color, but also that there is a cultural competency piece that’s missing,” Pacheco said. “Even if the prerogative is not to hire more teachers of color, how can we ensure that the teachers that are at these schools are culturally competent and that they understand what the impact might be of being the only black student in your class?”

According to Pacheco, racism in areas like Marin is often times implicit and can be the result of that lack of recognition.

“What happens with privilege—white privilege—is that you are often blind to everyone else’s experiences because you only see it from your own experiences. I don’t think it’s intentional—that folks are coming and saying ‘I’m going to be racist,’” Pacheco said. “I think a lot of it is a lack of space to dig deep on how race, class, socioeconomic status and gender are really interwoven into our systems.”

Principal David Sondheim echoed these sentiments and said Redwood is working towards creating a space where issues such as race can be openly discussed. To do so, Redwood’s staff has been teaming up with the non-profit organizations Pacific Education Group, and the Anti-Defamation League in an effort to train teachers on how to be more cognizant of the challenges minority students face.

“It’s incumbent on us to try and adjust our system to work better for students of color so that they are being more successful, attending [school] more, and there are fewer behavior challenges,” Sondheim said. “And so what we’re trying to do is a bit multi-pronged. We’re trying to raise the awareness of equity and racial conscience of our school community with our staff, students and parents.”

The goal of this initiative is to create an environment that encourages a dialogue about privilege and race, so that all members of the community have a better understanding of how they contribute to the fabric of this society, which in turn should make them more aware of the position of others as well, according to Sondheim.

“We’re trying to raise the level of inclusivity and respect for each other among all the people that are at school together, so that we get closer to everyone feeling that this is their school. Hopefully those changes will manifest themselves through adjustments in how we treat each other, support each other and learn from each other,” Sondheim said.

Students will play a specific role in the movement towards a more tolerant school environment according to Sondheim. Staff members are in the process of being trained by the Pacific Education Group, and they will then pass this information along to a specific cohort of students. These students, who will be part of the Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) group on campus, will then be trained on their own and with staff over the course of a year to gain the skills they need to be leaders at Redwood, fighting for racial equity.

According to Sondheim, once the students have these skills and leadership tools, it will be up to them to decide how they will use the abilities to benefit the community.

“I can imagine anything from these students feeling more comfortable and skilled to interrupting a conversation that they hear where someone has clearly been inappropriate or not taking in someone’s point of view effectively, all the way to making sure students of color can be successful in programs,” Sondheim said. “[They could] also provide the type of supports that might be necessary for students of color that white students have never thought of.”

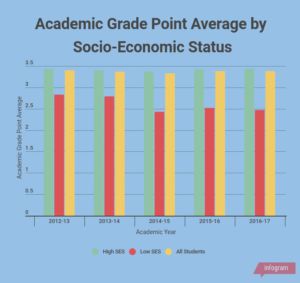

However, inequity at Redwood goes beyond just that of race. According to district data, last academic year students of lower socioeconomic status had an average GPA of 2.47, which was .96 lower than than the average GPA students of higher socioeconomic status’ by nearly a full grade point.

According to school counselor Tami Wall, the counseling department has put in place a new system that allows students from low socioeconomic backgrounds to apply for an allocation of money to cover the extra costs of being an involved student on campus, as well as during after-school hours.

“There are financial costs, even as a public high school, and Redwood has a new mechanism that is meant to capture the families that are in financial need so that they do not feel separate just because they can’t afford that yearbook or prom ticket,” Wall said.

Just as there are systems in place at Redwood that make being a minority race in school more challenging, such as a lack of diversity in the counseling department, likewise there are aspects to the school’s curriculum that hinder students of lower socioeconomic status, which is an additional challenge students must overcome.

“I’ll use the wifi example; if a homework assignment is requiring internet, we could very well have a student that doesn’t even have access to internet. That’s not going to be the general population, but it does happen,” Wall said.

Sondheim said he hopes that the same tactics of increased awareness and consideration for students of different races can also work as an approach to be mindful of those from varying socioeconomic backgrounds. A large issue surrounding compassion and sensitivity toward disadvantaged students is that those a part of the majority race and socioeconomic status can become blind to the privilege they benefit from. According to Sondheim, White students are able to see themselves reflected in the curriculum and culture at Redwood, which makes it hard for them to see the advantage they have over students of color.

Of course, tackling the issue of white privilege then begs the question, will a more balanced school system take away from White students’ likeliness of being successful? But lifting one group up does not have to mean knocking another group down.

“People are not comfortable with the privilege that they have, and they are afraid that they will have to give something up,” Sondheim said. “People think you have to give away to get, but I think we can do things differently so that everybody gains.”