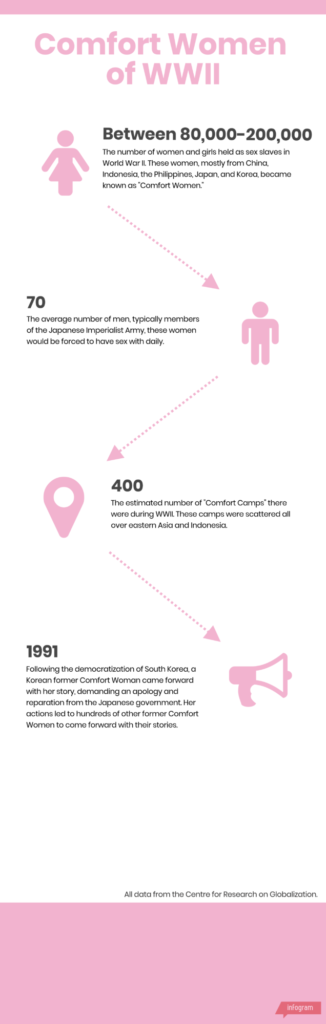

During World War II, the Japanese Imperialist Army coerced between 80,000 and 200,000 women and girls, mostly from China, Korea and the Philippines, into sexual slavery and brothels in occupied regions throughout eastern Asia. These women became known as “Comfort Women,”—a loose translation of the Japanese word for prostitute—and were forced to have sex with up to 70 men per day, according to the Comfort Women Justice Coalition.

After the war ended and these camps were dissolved, San Francisco established a “sister city” relationship with Osaka, a city in Japan that was almost entirely destroyed by U.S. bombings. This status is a long-term diplomatic and cultural partnership approved by the highest elected official from each community, and was established in order to “support individual and civic exchanges that foster better understanding and appreciation between citizens on both sides of the Pacific Ocean,” according to the SF-Osaka Sister City Association. It was a poignant display of acceptance and peace between two former enemies.

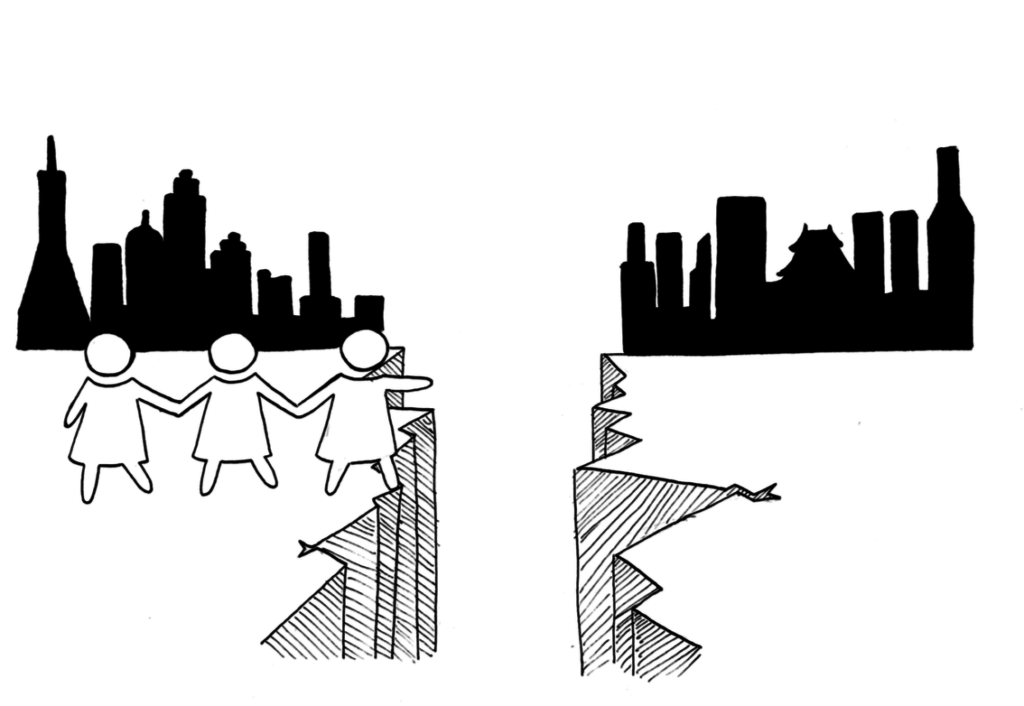

Fast forward 60 years, there has been exponential social advancements in both of these countries, relations between the two have remained relatively amicable and yet Comfort Women still struggle to have their stories heard. This changed in San Francisco in October, when a statue dedicated to these women and girls was erected as a city monument. The statue is elegant in its simplicity, depicting three girls in a circle holding hands.

Soon after, the mayor of Osaka, Hirofumi Yoshimura, ended the sister city status with San Francisco, calling the statue a “betrayal of trust,” and labelling it a one-sided and anti-Japanese portrayal of history.

For Osaka to end relations with San Francisco over the Comfort Women statue is perpetuating an archetypal habit of trying to erase the ugliest parts of a nation’s history—but in doing so, it assumes that this problem was specific to the time period, and ended when WWII did. The sexual slavery of WWII was a product of the inherent sexualization and abuse of women that has been constant throughout history, present in every civilization and society. Similarly to how racism didn’t cease when the Civil War did, the subjugation of women didn’t end with the closure of the Comfort Camps.

The Comfort Women statue isn’t a reminder of the horrific acts committed by the Japanese army, but rather the strength of these women; this statue gives a voice to not only Comfort Women, but to all women who have been victims of sexual abuse. In a country and world that at almost every point in history has tried to dehumanize, devalue and silence women, the creation of this statue is more than just a marker of an unfortunate time in history—it is a stance against the persisting and all-too-prevalent culture of telling women and girls (both directly and indirectly) that they aren’t worth as much as their male counterparts.

By condemning this statue, Osaka is trying to remove itself from its history. Critics of the statue state that it promotes an unbalanced historical attack on Japan—especially considering that thousands of Japanese Americans were held in internment camps at the same time as the Comfort Camps. This statue doesn’t serve as an American attempt to vilify the Japanese for the ugly moments in their history, because it is impossible to deny that American history isn’t also tainted by similar cruelties. The Comfort Women statue doesn’t stand against Japan; it stands with these women. By trying to ignore or forget the injustices of the past, we neglect and marginalize the oppression these injustices imposed on others. To forget Comfort Camps is to forget Comfort Women—to forget their hardship and their bravery—and attempt to silence their struggle. As long as these women carry their struggle with them, it cannot be swept aside or forgotten. As long as sexual inequality exists, Comfort Women cannot be swept aside or forgotten.

In this country, we have recently entered a new era of female emboldenment, with hundreds of women coming forward with their stories of sexual assault and harassment by powerful men; an era in which women don’t accept injustice, but challenge it. It’s time for Japan to follow suit. It’s time we enter a world in which we don’t hide history, but confront it.