On Tuesday at 8:50 a.m., Sept. 19, 2017, students sat in the dark under their desks, rumors buzzing over Snapchat and text. There was an alleged bomb on our campus. Word had it that the bomb was located in a trash can by the ampitheatre. In room 205, where many of my peers and I were located, whispers broke the silence. Our teacher crouched under his desk, bringing his head up just enough to see his computer, anxiously waiting for an update from administration.

The first classes to be released by the police were evacuated within 20 minutes. However, some classes didn’t evacuate to the football field for another hour, and one class was even forgotten about and left inside the building for an additional hour and half. If a bomb in fact had been on campus and been detonated, lives could have been lost due to the egregiously slow pace of the evacuation. According to the Educator’s School Safety Network, “In the 2015-2016 school year, U.S. schools have experienced 1,267 bomb threats, an increase of 106 percent compared to that same time period in 2012-2013.” With the increase of bomb threats, it is crucial that the evacuation process is improved upon.

Though I understand that keeping 1900 high school students under control is a difficult task, getting them out of a potentially dangerous area as fast as possible should be a priority for those in charge. Dismissing class by class is procedure, however, it may have been faster to evacuate and search classes two or more at a time and distribute more police in the building.

The most troubling part of the way the bomb threat was handled regards the time at which the threat was called in. According to Marin IJ’s report on the incident, “The threat was called in Monday evening and received by school staff at 7:26 a.m. Tuesday.” If administration knew about the threat before classes were in session, it begs the question: why weren’t classes immediately canceled? Though it is important to determine the legitimacy of the threat, it would have been far safer for the students and saved all of us at least four hours of being scared and confused on the football field if we were all just sent home.

The dismissal process was no smoother than the evacuation. Administration announced through the loudspeaker on the field that students could be individually dismissed once a parent called into one of two phone numbers provided to authorize their child’s dismissal. With 1900 students, it is no wonder that the lines were constantly busy.

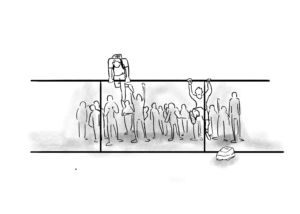

There was also the issue of 18 year-olds, legal adults, being barred from leaving. I watched as an 18-year-old boy stood at the gate saying “I am my own legal guardian, may I leave?” as admin turned him away. At about 12:20 p.m., several students decided to hop the fence to escape the field, inspiring many more to follow suit. In the parking lot, some students were driving in the wrong direction due to the crowding and confusion. Though the dismissal process was handled poorly, it is not considerate or fair to the police enforcements and our faculty to disrespect their efforts to keep us safe.

It was, however, very comforting to see the police blocking off the center of the school when dismissed. Though the bomb had been deemed no longer a threat, police continued to ensure safety for students walking to the back parking lot. Given what little information administration had, it is clear that every staff member was working hard to keep everybody as informed and safe as they could. As problems arise, we must unite as a community and have faith that administration is doing everything they can and are working to improve on the procedures. Unfortunately, this was not the case with the bomb threat.

Though we are extremely grateful for the efforts put forward by administration and police personnel during the threat, there were some crucial mistakes made that could have made the difference between life and death if this threat had been real. In the future, with a smoother evacuation plan, we will be able to look back on this situation as a lesson Redwood has learned. According to the National School Safety and Security Services, many schools do a poor job handling bomb threat evacuations. This poor execution is a much broader issue than just Redwood. In 1999 a bomb at a Kansas City high school went off, sending 11 students to the hospital, according to the National School Safety and Security Services. To better our process, administration is taking the appropriate steps to correct the flaws for future situations.

“Effective tomorrow, [administration will be] implementing a new dismissal procedure,” Sondheim said in the most recent email about the situation. It is a relief to have the prospect of a more effective system. It would be best to practice a bomb threat evacuation and dismissal drill at least once a year to avoid the confusion and chaos we saw take place.