Today, the controversy over Confederate monuments is not simply about statues—similar to how the Civil Rights movement was never just about drinking fountains.

The issue over Confederate symbols encapsulates a series of long-standing national conflicts, reignited by last month’s deadly clash at the White supremacist rally in Charlottesville, VA.

Confederate memorabilia is not only concentrated in the South, but is scattered throughout the country. Just three hours south of the Bay Area in an unincorporated area of Monterey County, lies a town called Confederate Corners. For years, there have been debates over changing the name. California State Sen. Steve Glazor proposed legislation in 2015 that would require public places with names linked to the Confederacy to be renamed. However, the bill was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown. When asked if he is now reintroducing the bill, a spokesperson for Sen. Glazor said that he is “evaluating the situation,” according to Mercury News.

Since the rally in Charlottesville, around 23 of 700 Confederate monuments have been rightfully removed throughout the country in cities such as Helena, MT; Brooklyn, NY; Louisville, KY and more locally in San Diego and Los Angeles, according to the New York Times. In August, the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles took down a monument honoring confederate veterans after hundreds of activists called for its removal. Within the same month, the city of San Diego took down a plaque commemorating Confederate president Jefferson Davis from its downtown area, according to the Los Angeles Times.

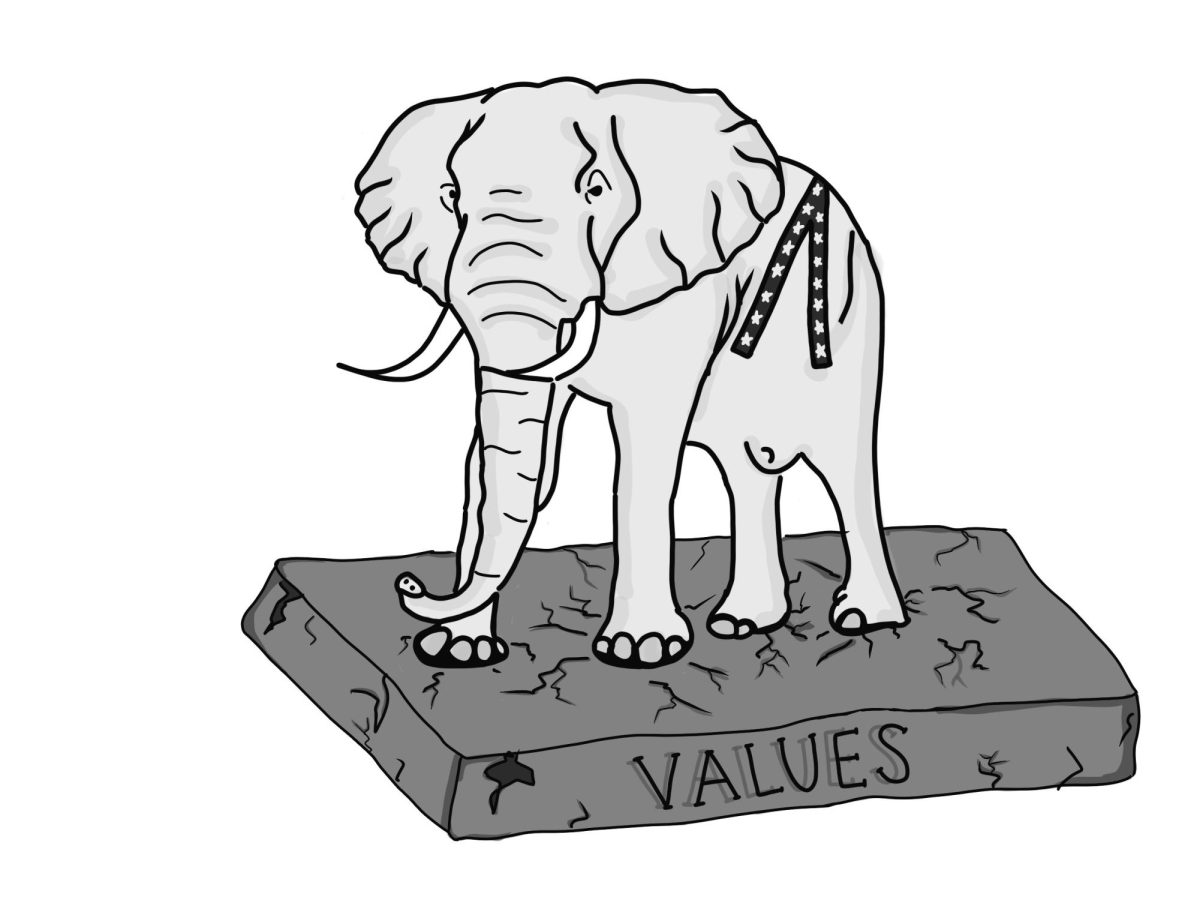

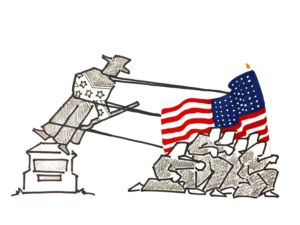

Although removing historic monuments may be seen as unpatriotic or as an attempt to erase the past, such action instead represents reform efforts to cease the antiquated, often hateful, ideologies that these statutes reflect. These figures will not be forgotten; the effects of their complex legacies will remain in America, but they should not be granted the honor of occupying our public spaces.

Rather than publicly preserving these monuments, the statues should be relocated to museums where they can be adequately contextualized in America’s complicated past. To fill the vacated spaces, monuments of figures who represent the epitomical values of the country should be erected. Their removal presents an opportunity to display heroic figures among traditionally marginalized groups of people, such as Native Americans, African-Americans, Hispanics, members of the LGBT+ community and women. Figures such as Leonard Matlovich, the first service member to come out in the military and fight their ban on homosexuality, Susan Le Flesche, the first female Native American to earn a medical degree and become a physician in the United States and Audre Lorde, a feminist, civil rights activist and poet, are deserving possibilities. With the removal of these statues, the American people are presented with the opportunity to celebrate more recent and relevant figures.

As Erika Doss, an American Studies professor at University of Notre Dame, said in a New York Times opinion piece in August, “Memorials and monuments have a lifespan, not unlike the human body. They’re symbols at certain moments. Values change, histories change.” In fact, it is part of our patriotic past to take down statues that no longer accurately celebrate our principles. During the American Revolution, New Yorkers removed a statue of King George III at Bowling Green, as its existence represented a monarchy that no longer aligned with Americans’ desire for democracy.

Ideally, the removal of these monuments will inspire discussions of ways to acknowledge America’s complex past while reforming its present, and serve as a reminder that there is still much to be done to reach racial equality; by taking the statues down, we are making strides in the right direction and setting the tone for the future.