“UnPresidented” is a new column discussing the transition and first days of the Trump administration.

On Thursday, President Donald Trump finally revealed his administration’s proposed budget. Along with the long-rumored $54 billion hike in military spending, the Trump administration also proposed massive cuts in domestic funding, including anti-poverty and education programs, and the State Department. The State Department, headed by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and responsible for diplomatic endeavours and relationships with foreign nations, was placed under the axe for a reduction of 32 percent resulting in a budget of $39.1 billion, the lowest in 14 years.

With the deficit essentially remaining the same, Trump has traded foreign relations for military spending. And while the budget is simply an agenda-setter that still needs Congressional approval, the move marks a shift in American foreign policy from diplomacy to military actions, and from co-optive power to coercive.

In his 1990 seminal book on the topic, Harvard’s Joseph Nye writes on two types of political power. The first, known as coercive or “hard” power, deals with military actions and forcing others to do what the state wants, whether in the interior or in international relations. The other type of political power, co-optive or “soft” power, is the means by which, as Nye writes it, “one country gets other countries to want what it wants.” Soft power is characterized, then, not by force, but by a country’s ability to set the political agenda, and gain legitimacy through soft power resources such as culture, ideology and international institutions.

Trump’s budget proposal has far more emphasis on the hard than on the soft. This should come as no surprise considering his character and the image he presents. As evidenced by his Twitter account and campaign promises, Trump is the type of president who is constantly on the attack. For one example, instead of working diplomatically with Mexico to solve issues with immigration, Trump’s solution was to propose a wall and to make Mexico pay for it. As shown by the Mexican president’s cancellation of a visit to the U.S. in January over the issue, relations with the country have not improved as a result.

The issue with this Trumpian philosophy is that the international power balance is much more dependent on soft power in this increasingly globalized age. Economic interdependence leads to political interdependence, making coercive policies less attractive and much more costly. The global political climate has changed in years since World War II, and as a result, money and military power are less transferable to political power, as Nye noted.

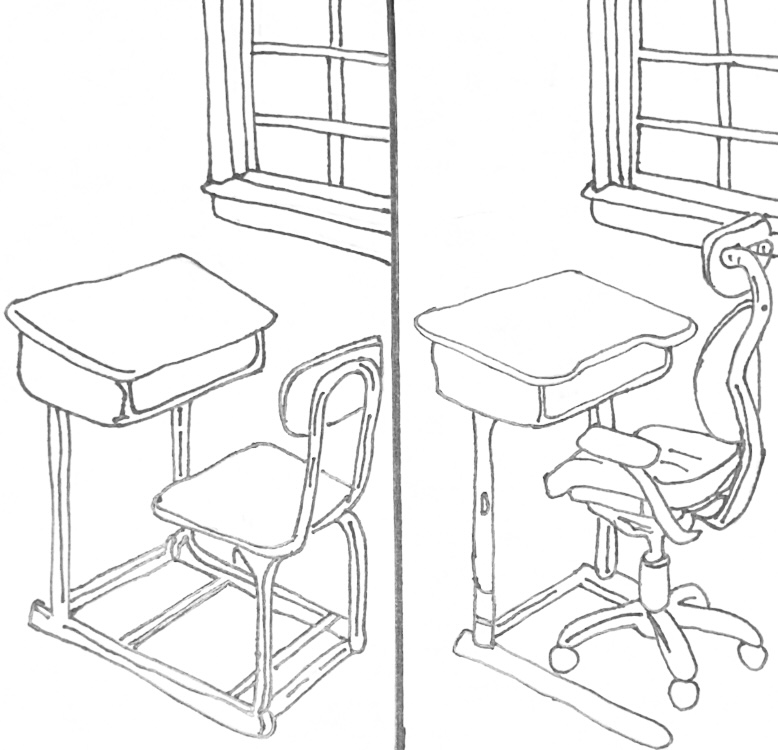

If this were the 19th century and states relied more heavily on coercive tactics, Trump’s approach would likely be very effective. In the past, a strong military meant more territory, which meant more resources and a stronger treasury, and as a result, a stronger state. That is no longer the case. These days, “soft” resources such as technology, education and economic growth are more significant in international power than population or geography.

It is now much more difficult for large states to effectively take over weaker states through military force. Consider the U.S.’s experiences in the Vietnam War. Vietnam did not become a more powerful military nation throughout the course; rather, increased social mobilization made U.S. military intervention more costly. No longer is complete imperialism possible through the deployment of troops.

Throughout history, politicians have called for coercive rule over all else. Consider Otto von Bismarck’s 19th century remark that “policy cannot succeed through speeches…and songs; it can be carried out only through blood and iron.” Yet, it was not war that made Germany a world power or made Bismarck a realpolitik, it was his diplomacy and balance of power techniques. And it is not increased military action that will create peace and American influence today.

Hard power is still necessary today. The U.S. military does serve a very important role in foreign policy. Yet coercive power is not effective without strong co-optive power. For America to remain a strong power, we must not only assert military force, but create legitimacy through our soft power resources. It is much more beneficial for the U.S. to retain its image of the ideal land of freedom as a way to be accepted as a legitimate authority.

The U.S. currently has many of the soft power resources necessary. For one, many major economic institutions are based in the U.S., such as the International Monetary Fund, and thus global economic policy is often based in American ideals. A Pew Research study in 2016 (prior to Trump’s election) also found that there is a fairly favorable view of the U.S. in 15 significant countries in North America, Europe and Asia. And across the data, the populations of all countries but Japan responded with a majority saying that the U.S. has remained as important and powerful a world leader as it was 10 years ago. Perception matters, and the U.S. is set up well to continue its importance in the global sphere. Cultural perceptions and exports were what made the U.S. come out on top in the Cold War, not military actions.

But a Trump presidency has begun to threaten the soft power resources we hold. The budget he’s proposed not only cuts down on diplomacy, but also cuts down on funding for arts and education, two of the most important soft power resources. Trump rose to the presidency on fears of an American decline, and it has truly become a self-fulfilling prophecy. With anti-Trump protests across the globe during his inauguration and less than stellar relations with some close allies, the perception of America abroad is in a crucial and shifting period. With Trump’s budget proposal and apparent protectionism, America is losing, instead of gaining, crucial influence.