Before making history as the first African American president of the United States, Barack Obama was just Barry. A native Hawaiian, chain-smoking, biracial Columbia undergrad, Barry had not yet embraced his political potential. “Barry,” a Netflix Original, examines Obama’s life as a Columbia student in 1981.

The movie opens with Barry (Devon Terrell) smoking on a plane about to land in New York. He takes the subway to his new apartment, quietly absorbing the boombox-blasting, graffiti-decorated chaos of Harlem. There, he almost gets hit by a car, and we hear the first word of the man now known for his eloquence, “Shit!”

Before I watched this movie, I wondered how its plotline would be structured, given that almost anyone in the audience would know the end—Barry would later move on to a distinguished political career, marry Michelle and eventually become President Barack Obama. I thought that watching this movie would be like starting a book by first reading the last page. I was dubious about this movie’s capacity to entertain me, considering that I already knew the climax in Obama’s life. However, “Barry” focuses not on Obama’s political career, but on the emotional turmoil that led him to a lifetime of civil service. “Barry,” was a pleasant surprised in it’s human capacity, not the superhero plotline that so often consumes movies. Emotionally conflicted, Barry struggles to answer the seemingly simple question “Where are you from?” It is a question he genuinely does not know the answer to—is he from Kenya? Kansas? Hawaii?

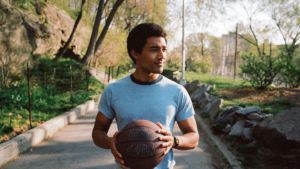

This is the conflict that “Barry” centers itself upon. Barry can’t decide whether he aligns himself with his father’s African origins or his mother’s midwestern roots. The movie reflects Barry’s difficulties in navigating his racial identity—he’s the only black man in four out of his five classes, he’s awkward socializing with his wealthy (and almost entirely white) peers and he’s uncomfortable in the poor public housing projects. The Barry who plays basketball at the Columbia gym is not the same Barry who plays at the street courts. The five blocks between the Columbia campus and the poor New York City slums symbolize the chasm Barry feels within himself.

The scenes are cool and compact: sets are muted and the colors are subtle. There is no real climax to the movie, no startling realization or epic battle against an enemy. The movie is confounded in nuances; it doesn’t celebrate the melodrama that is all too common in coming-of-age movies. Rather than being explicit in its expression of racial tensions, “Barry” presents itself as a series of tests in the form of small interactions. “Barry” is not a movie about a young black man fighting the world’s injustices, but instead a movie that utilizes the pressures of the outside world to expose the real fight: his internal one. This movie does not portray Barry as a victim of oppression, but one of his own mind.

Though the scenes are, if anything, slightly underwhelming, perhaps the most stunning aspect of “Barry” is Terrell’s portrayal of Obama. His slow, controlled movements, and deep, velvet voice are a near perfect imitation. Terrell is extremely convincing as Barry, capturing his charm and intellect without any breaks in character throughout the movie. Terrell’s performance is backed by equally impressive supporting actors: Anna Taylor-Joy as Charlotte, Barry’s white classmate and girlfriend (a cute, geeky relationship which we know is ultimately doomed), who naively believes that racial stereotypes won’t exist if you simply ignore them, and Jason Mitchell as PJ, Barry’s friend from the basketball courts in Harlem who we later find out is a business school student at Columbia. These characters represent the spectrum upon which Barry cannot find his place, from the wealthy white to the poor black.

At times, “Barry,” becomes clichéd, such as the ending, where Barry finally signs his name as Barack, seemingly coming to terms with his identity. For a movie characterized by Barry’s struggle, the end is too feel-good and conclusive—suddenly, Barry has become Barack, with no real explanation or self-realization. This subtracts from the realism of the movie, making it feel less honest and human. This ending is too easy, which, while not uncommon, is especially disappointing, considering the nature of Obama’s persona. The President Obama we know is one crafted by a series of public appearances meticulously planned by White House aides, press associates, and speechwriters. The movie’s ending takes away from the raw themes it cultivated, and reminded me of corny voice-overs at the end of superhero movies.

Though Obama’s presidency has concluded, “Barry,” while imperfect in its progression, is a phenomenal movie providing insight into the making of the man who has shaped America for the past eight years. “Barry” elucidates an important and too often forgotten message: to embrace life as a grayscale instead of only seeing it in black and white.