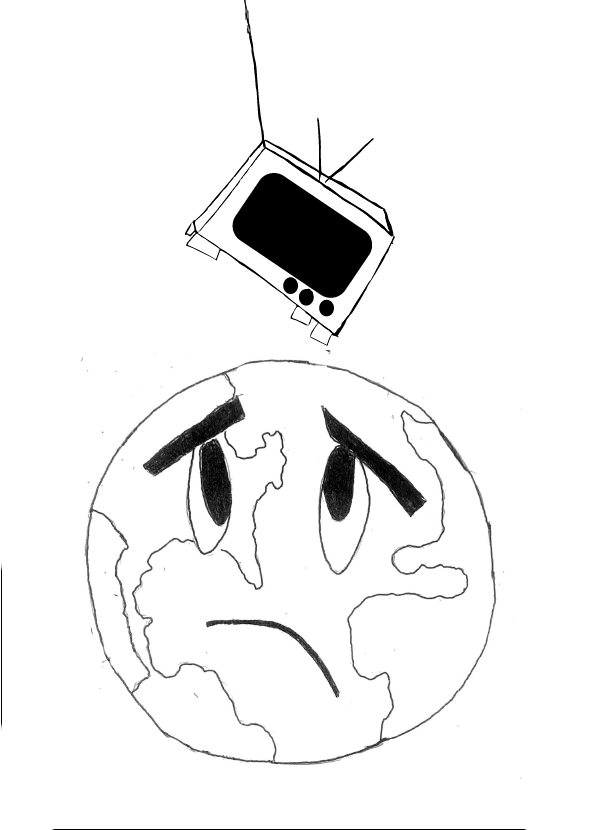

Amid tweet-storms and controversial comments and speeches given at an unprecedented “Thank You Tour,” it seems that all president-elect Donald Trump’s been doing is communicating with the American public. However, one type of communication between the country and the president-elect has been noticeably absent. Until last Wednesday, it had been half a year since Trump gave a press conference.

There was much to address at Trump’s Wednesday meeting with the media, but Trump’s main focus and reason for calling the conference, namely his plan for disentangling himself from his business interests, stands out as an issue that will no doubt plague the administration for the next four years.

To address his plan to move forward conflict of interest free, Trump placed control of his massive company, the Trump Organization, in the hands of his two sons, Donald Jr. and Eric, claiming that there won’t be any discussion of the company between him and his sons.

Trump’s solution to his foreign business entanglements pales greatly when considered against the actions of most other commanders-in-chief. With the small exception of Obama, whose only assets came in the form of mutual funds and Treasury bonds, most other presidents in modern American history, including Lyndon B. Johnson, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, both George Bushes and Bill Clinton, all placed their considerable assets in a blind trust. A blind trust, simply, is an arrangement in which a government official puts control of their assets in the hand of a third party which acts without the knowledge of the official in order to avoid conflicts of interest.

Trump’s claims that he doesn’t have to give up control of his business are valid. Title 18 Section 208 of the U.S. Code, which prevents executive branch employees from participating in government actions that will affect their, or their family’s financial interests, has an exemption for the President.

But just because Trump can keep control of his business doesn’t mean he should. The Trump Organization differs from other types of assets because of its business with foreign countries. Trump cited involvements with 500 different companies on his financial disclosure filings, some in countries with which the U.S. has complicated diplomatic relationships, such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and China; many other foreign business dealings are still shrouded in secrecy.

And whether or not Trump chooses to engage, more foreign companies are chomping at the bit to work with him. In the press conference, Trump noted that Damac, a large developer in UAE with ties to the UAE government, attempted to reach a multi-billion dollar deal with the Trump Organization, which the company declined.

Foreign business entanglements are precisely what have led to claims that Trump will be violating the Constitution the minute he takes office. The part of the Constitution in question is the Emoluments Clause of Article I, Section 9, which would prevent Trump from accepting “any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.”

A report by the nonpartisan Brookings Institute found that Trump will almost certainly be violating the act, with prominent examples such as his recent construction of a hotel from diplomats, restart of projects in Argentina and Georgia and the fact that the Chinese government is the single largest tenant in Trump Tower.

Trump is a president without precedent in many ways. The richest commander-in-chief by a landslide, Trump’s assets, whether at the low-end of a $3 billion estimate by Bloomberg, or his own announcement of wealth “in excess of $10 billion,” are vastly more than that of any other president. The complete disentanglement from his business interests would not be simple, but instead would take a number of years due to the scope and type of business he’s involved in.

But Trump still needs to take additional steps to remove his conflicts of interest, although that doesn’t seem likely given his actions in the past months. For one, consider what he did regarding a wind farm in Britain that would block the views of his golf course: Trump broached the subject in a meeting with prominent British politician Nigel Farage. While wind farms and golf courses may not seem like a big deal, Trump is setting a precedent that he will use his office as president to further the interests of his business. What is best for the Trump Organization is not always what is best for the country on the whole, and the influence of self-interest runs the risk of straining foreign relations.

And while Trumps continues to make his “no new deals” promise, he’s restarted old developing projects in Argentina and Georgia since his election, showing that he is willing to continue to engage in foreign countries, and more important in foreign countries that are not the U.S.’s closest allies.

A large part of Trump’s role as the president lies in diplomacy and foreign affairs, and his unwillingness to completely separate himself from his business and his foreign business entanglements bodes ill for foreign policy in the next 4 years.

“UnPresidented” is a new weekly column discussing the transition and first days of the Trump administration.