Sections in history textbooks augment inequality

In most history textbooks, events are separated into sections. We learn about life on the homefront during World War II and the presidents during the 1920s. Then comes the next section: women.

The fact that women’s history is separate from history itself suggests that women weren’t a vital part of the past. They may not have been presidents or generals, but there is more to the past than male leaders. Fifty percent of the population deserves more than a few paragraphs in a 20-page chapter.

This isn’t just true for women, however. In the US History textbooks, there are subsections for Black and LGBT Americans in some chapters. In others, these groups aren’t mentioned at all. The worst part is that the textbooks with these sections are some of the most inclusive I’ve read. Textbooks from my middle school didn’t even touch on LGBT issues, and one of few Black Americans we talked about was Martin Luther King, Jr.

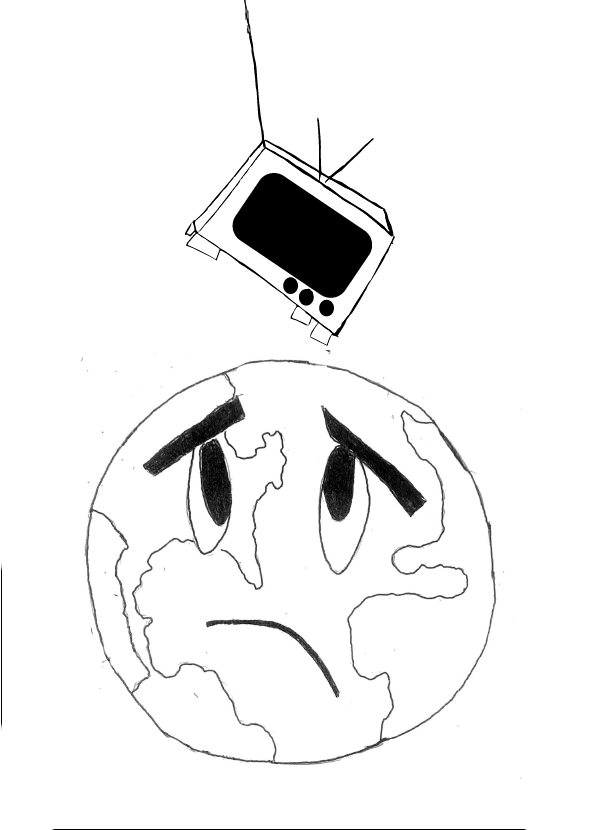

The separation of women, other races and other sexualities in history textbooks maintains the idea that history really is his story, as told from a straight White man’s perspective.

If somebody asked me in my history classes about LGBT history, the only events I could recall are Stonewall and Harvey Milk. I didn’t learn about the White Night riots, which occurred after the trial for Dan White, who was responsible for Milk’s assassination, or Jeremy Bentham’s fight for the legalization of homosexuality.

Much of society simply accepts the emphasis on White men throughout history. The phrases “women’s history” or “Black history” aren’t uncommon. But “man’s history”? “White history”? Nobody has ever needed to specify that it’s about straight White men—after all, that’s what history is.

If we believe that the only important historical events involve straight White men, then we are taught to believe that they are the most important members of society.

Furthermore, the categorization of history into women, Black, and LGBT issues, falsely assumes that these three groups are completely separate: Many people in the past and present belong to more than one. When we don’t learn about people subjected to more than one disadvantage, we don’t understand the full extent of their experiences. Gloria Anzaldúa, a feminist and queer theorist explained this when she wrote, “The lesbian of color is not only invisible, she doesn’t even exist.” We are furthering ignorance of people experiencing intersectionality, a term used to describe the simultaneous actions of many systems of oppression worker together, when we learn history from a White man’s perspective.

White feminism, for example, is the focus on problems White, middle-class women face, such as being paid 79 cents to the man’s dollar, according to National Partnership. Meanwhile, Black women in the United States are paid only 60 cents to the man’s dollar, on average. This focus on the issues facing solely White women is a result from our society’s narrow view of inequality—that it affects only one group at a time. This ignorant view is only furthered by our study of history, and the separation of marginalized groups into sub-categories.

When we learn about the history of oppression, we hear a very limited view—if it’s Black history, it’s about straight Black men. If it’s women’s history, it’s about straight White women. If it’s about LGBT history, it’s about White men. Minority groups are compartmentalized, even more so if they belong to more than one, and that makes their needs easier to ignore.

There is more to feminism than equal pay and more to LGBT rights than marriage equality. LGBT women of color living below the poverty line sometimes can’t fight for equity because they are too busy fighting to stay alive. They may have words, they just don’t have time. And then Anzaldua’s quote becomes true: Those victimized by intersectionality become nonexistent in our eyes because they are so easily ignored.

It is vital that history encompass all perspectives and all tales. Textbooks should tell history from every point of view possible so that we as students can see a broader picture of what was actually happening at the time, and open our eyes to the injustices that are still present today.