Algebra P1-P2. Honors Chemistry. Geometry 1A. Honors Geometry. These are four classes that the Redwood administration did not offer this year. They did offer standard classes such as regular algebra, regular geometry, and regular chemistry.

The administration’s decision meant that students who had excellent grasps on chemistry and geometry were forced into slower-paced classes, and students who weren’t ready for a full year of algebra were left struggling to keep up, according to a recent Bark article.

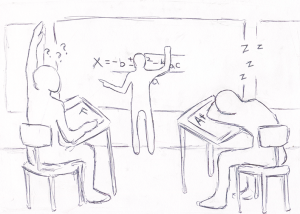

Redwood offers few remedial or honors level courses, especially during the first years of high school, so a majority of classes for underclassmen contain students of varying abilities shoved together into one classroom, with a single teacher trying to figure out how they can meet every student’s needs.

Ultimately, they can’t. In classes where students are lumped together regardless of ability, it is impossible for teachers to fully support those who may not learn the material as quickly while simultaneously challenging those who have already mastered it.

Required classes with no alternatives, such as Integrated Science 1-2 or English 1-4, must have a “consistent message of what students are expected to learn,” according to the Common Core State Standards Goals. Theoretically, all students will learn effectively in these courses and understand that “consistent message.” However, my own experience suggests those at the ends of the ability spectrum do not get their needs met.

In my earlier Spanish classes, I always felt we were moving at a glacial pace, and that I never had any opportunity to advance my own learning. In my freshman English class, I felt challenged just the right amount. In my chemistry class, I occasionally feel completely lost after the day’s lecture.

Often, when people say that required classes don’t meet the needs of all students, critics counter that teachers can differentiate their teaching so that all students are able to further their learning.

In my experience, however, “differentiating” means enlisting high achievers to teach lower achievers the material. Though this might help higher achievers gain an even greater understanding of the material, it doesn’t allow them to learn new material.

A study from the Fordham Institute surveying teachers in various public schools throughout the nation found that 81 percent of teachers “acknowledge that it is difficult to tailor instruction to match the individual needs of students on a daily basis in the classroom.”

It seems only plausible that Redwood teachers face the same struggles, despite the school’s stellar reputation.

Because teachers are not able to properly differentiate instruction to accommodate a wide range of ability levels, it is necessary that more class levels be offered at Redwood so that students have the opportunity to learn at an appropriate pace.

Redwood’s class sizes of 25 or 30 make for slim chances that a classroom could be populated with students of the same ability, unless it is a remedial or advanced class. Additional specialized classes are necessary so that teachers can gear instructions toward the specific abilities of their students.

The same study by the Fordham Institute also revealed that teachers believed that teachers are generally more effective if students are “grouped homogeneously by ability” than if classes contain students who are “mixed in ability.”

Furthermore, students in classes grouped by ability performed better by a “significant” margin on “achievement examinations” than students in standard classes did, according to the American Educational Research Journal. More important, however, students in grouped classes were more likely to enjoy the subjects they were studying than those in normal classes.

Because students not only learn better in classes when they are with students of like ability, but also enjoy them more, Redwood should offer more classes like Algebra P1-P2 and Honors Geometry―classes where students can work up to their full potential.