Principal David Sondheim sent a set of guidelines to the Redwood community about the week preceding final exams, formerly known as “Quiet Week” or “Dead Week,” on Jan. 19.

The guidelines for the week, now called “Study Week,” were discussed and approved by the school’s Site Council, a group primarily comprised of students, parents, staff members, and administrators, including the principal.

The Site Council was presented with a complex issue, and any effort to bring uniform policies or rules to the week must be praised. But the guidelines are not enough.

The principal cited our community’s general “confusion” about the purpose of the week in his email about the guidelines, and proceeded to thank the Site Council for its dedication in “helping students be emotionally and academically successful.” One of the group’s primary goals was to “establish a clear definition” of what should take place during the week before final exams.

Yet the guidelines listed in the document and on the school’s website are anything but “clear” or uniform. For example, the Council states that athletic events and other extracurricular “performances” should “be kept to a minimum.” The guidelines also state, “We suggest that teachers avoid giving students large assignments or assessments during Study Week that would take away from their ability to prepare for their finals.”

But how is a student to make the most of their study time during Study Week when coaches are not bound to any concrete rule, and teachers are only prompted by suggestion? If the Site Council’s goal is truly to assist students in “perform[ing] to the best of their abilities,” athletics (among other “performances”) must take a backseat to academics, and the administration should require teachers to adhere to mandatory policies—without exception.

The guidelines also state that teachers “should avoid teaching new content if students will not have adequate time to learn the material before the final exam.” Whether or not students “have adequate time to learn” the new content is a purely subjective judgement on behalf of the teacher. Teachers will have the freedom to deem anywhere from four class periods to zero class periods as “adequate time” to understand new material, while simultaneously reviewing a semester’s worth of curriculum.

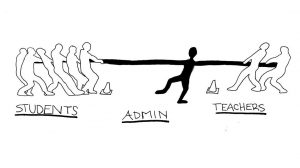

A recently released summary of a survey given to both teachers and students in May 2015 suggests that they have conflicting ideas about their priorities for Study Week, aside from a shared desire for “additional or extended SMART periods.” Among the top-ranked teacher priorities were “no field trips,” and “no non-essential call slips,” while students rated “no homework unrelated to the final,” and “no new material” among their own.

By including vague language in the guidelines, the Site Council and administration appease both students and teachers. These groups avoid addressing the concerns of the student body by endorsing such nonobligatory language as “suggesting” and “recommending.”

It is admirable that the administrators involved students and teachers in the planning process. The attempt to include student voice was a good first step toward facilitating discussion of differing viewpoints.

If administrators truly wish to promote academic and emotional success for students, however, they should approve rules, not guidelines, that teachers must follow. Because of the room for interpretation in the guidelines, we are only compounding the dilemma at hand, rather than lessening the “hectic” nature of the week that the principal described in his email.

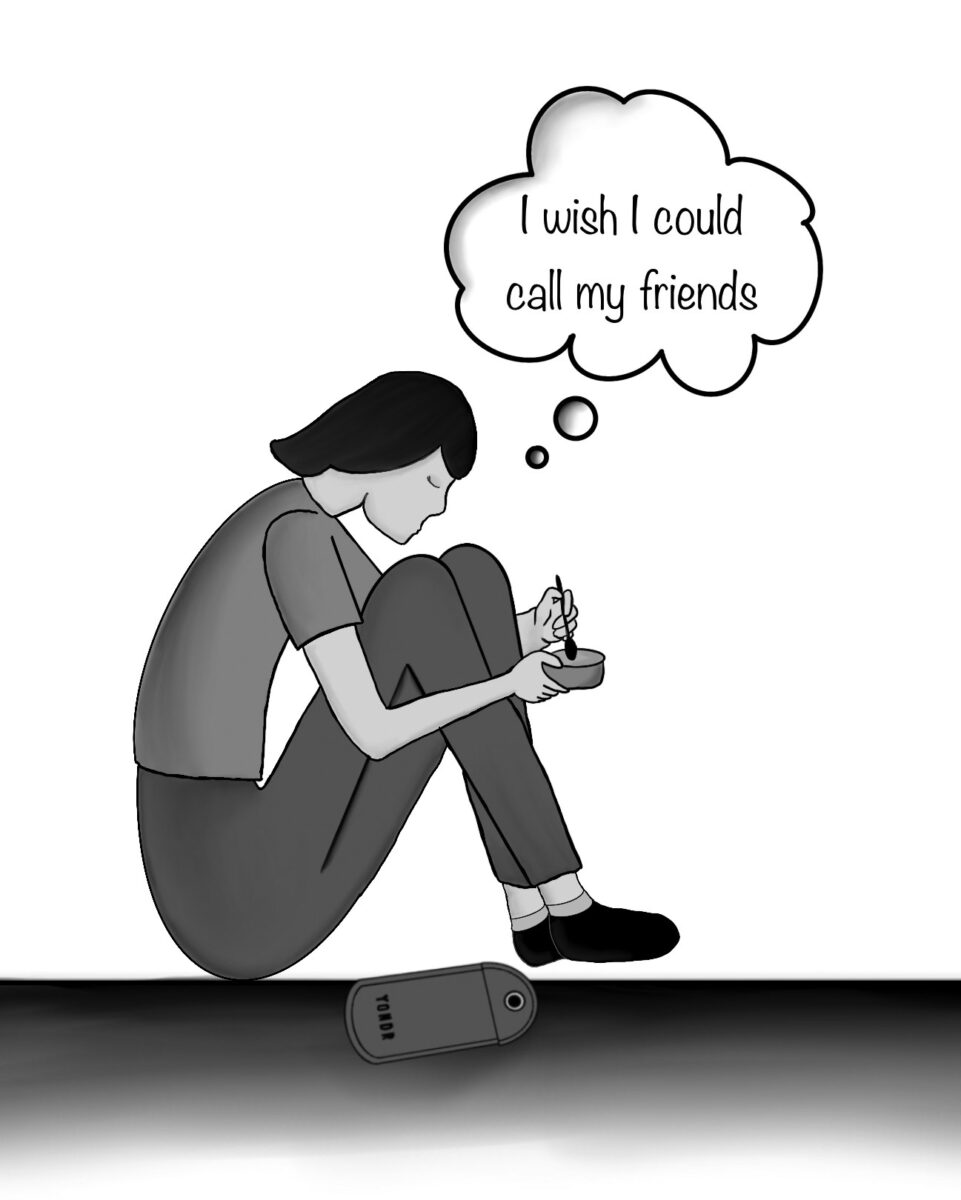

We cannot expect that all students will receive adequate time to learn without enforceable rules. Study Week should be reserved for studying and reviewing a semester’s worth of learning—this is what the students have demanded, and this is how we can best “alleviate stress and reduce anxiety.” We urge Principal Sondheim and the administration to make what may seem like an unpopular decision and act in the best interest of the students they are supposed to serve.