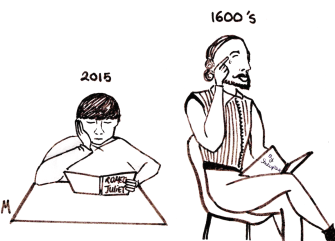

I remember my freshman English class where we were required to recite two pages of “Romeo and Juliet.” This was my first experience tackling Shakespeare, and I dreaded the idea of memorizing extravagant words with which I didn’t have the slightest fascination.

I attempted to understand the meaning behind each ridiculous phrase. But after reading the monologue once through, the thought of trying to find some sort of resonance felt much too overbearing.

I decided to try and memorize the words verbatim, but it felt silly. How was I to recite a monologue with emotion and intrigue if I had no clue what I was talking about? I’d never before felt the frustration of having to read something that felt so foreign. Reading Shakespeare was like learning a new language, except harder because this was English class, and I had to identify the underlying meaning between the lines of the text.

So, I went over each line, analyzing each word and translating each phrase until I could uncover the point. If no one in the society I lived in today spoke in such a manner, why should I try to understand it? What could I possibly learn from this?

In high school, there is only a small minority of students who understand and enjoy reading classic literature like the “Scarlet Letter” or “Macbeth.”

But the enjoyment of reading these books is not the point of studying classic literature.

Although the context of the stories often seems foreign and unrelatable to us, considering some of the pieces were written over 100 years ago, it is important to engage and challenge ourselves to find meaning in something that at first glance feels so meaningless.

I didn’t understand it at the time, but memorizing and translating each phrase of that monologue helped me to expand my own ways of expression. Before reading Shakespeare, I hadn’t realized how many layers a piece of writing could have. It was like unraveling an intricate puzzle that I never knew existed. And when I finally made sense of the text, I felt competent and able to conquer other challenges that had previously seemed daunting.

After finishing the Romeo and Juliet unit, I came to understand that despite language barriers, this was ultimately a story of two teenagers falling in love, and it made me realize that all humans, even long ago, struggled with the same issues we do.

While some classic literature wasn’t nearly as difficult to read, I have found myself struggling to relate to these books, either because of the archaic language or dialects that make it difficult to get through. However, if we put aside these classic books because they are no longer contemporary, we will miss out on important themes of humanity that still resonate today.

For example, “To Kill A Mockingbird” was written in 1960, and it covers themes of racial injustice in the South from a child’s foreboding perspective. Today, racial injustice continues to be a huge issue, as seen in current events surrounding police brutality, such as the riots in Baltimore and Ferguson.

When we’re forced to read classic literature, like “To Kill A Mockingbird,” it helps us empathize more deeply with characters, like Tom Robinson, a black man who was wrongly accused of a crime. It makes us think, when we look at the news today, about how long these struggles have been going on, and about how long one race has felt oppressed by another.

Although it is not the most enjoyable thing to tackle some of these texts, in the end I do think it’s important to keep classic literature on course reading lists. When we consider what we normally stream during the weekends, it’s important to balance our time with time-honoured content that connects us to deeper issues as well as historical context.

I have to admit reading Shakespeare is necessary, and despite the intensive deciphering in the process of studying classic literature, the end result is a way to strengthen our critical thinking skills and unify us in our connection to humanity.