In 2012, Kendrick Lamar released the Grammy Award-winning album “Good Kid, M.A.A.D City” to widespread critical acclaim. Some hailed it as a brilliant piece of storytelling, a triumphant resuscitation of West Coast hip hop. Others went as far as to call it an instant classic.

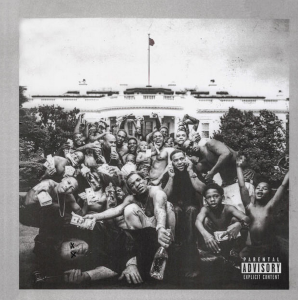

“To Pimp a Butterfly,” his follow-up album released on March 23, cements his place atop the hip hop hierarchy with a lyrical indictment of structural and cultural racism in America, stopping along the way to address self-hatred, self-love, and sexuality in an introspective manner. But, somehow, Lamar manages to do so without preaching, instead wielding anecdotes, personal narratives, and raw emotion as his weapons of choice.

As cohesive and complex as this album is, Lamar’s latest release is not for all hip hop fans. “To Pimp a Butterfly” strays far from mainstream sound, and well-known previous hits such as “Swimming Pools (Drank)” and “Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe” are absent from this project.

Instead, Lamar expands on his themes from “Good Kid, M.A.A.D City” of escaping his restrictive hometown of Compton. In fact, “To Pimp a Butterfly” features Lamar returning to his fateful city to educate his neighborhood on how to identify the “butterfly” within each “caterpillar.”

The album opens with a soulful sample of Jamaican singer Boris Gardiner and showcases George Clinton’s haunting vocals on “Wesley’s Theory”: “Gather your wind, take a deep look inside / Are you really who they idolize?” It doesn’t take long for Lamar’s posse of Flying Lotus, Sounwave, and Thundercat to kick in with a tense, funky groove that sets the stage for the first vignette.

In the first verse, Lamar takes the character of a young black man corrupted by his rise to fame and milked by the music industry. Like a caterpillar, Lamar’s sole aim is to consume the world around him—he does not yet know his potential. His second verse looks at the issue from the perspective of the “pimp,” here personified as Uncle Sam, as he asks, “What you want you? A house or a car? / 40 acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar?”

In “u,” Lamar screams the phrase, “Loving you is complicated” while spiraling into a depression caused by his commercial success and a recurring out-of-touch relationship with his community. Lamar exhibits his originality in this fervent track—no other mainstream rapper could be heard practically crying during a song and still receive praise from both critics and fans alike.

Throughout the album, Lamar weaves in a poem that ties together the narratives in each song. Once “To Pimp a Butterfly” transitions into its home stretch, Lamar transforms from an immature wanderer to a wise rhymesayer in “Momma.”

“Blacker the Berry,” one of the album’s few singles, expresses Lamar’s frustration with the black community as he struggles with his own place within it.

Of the album’s biggest surprises reveals itself in the final track, “Mortal Man,” during which he engages in a dialogue with deceased West Coast rapper Tupac Shakur. Using bits and pieces from one of Shakur’s old radio interviews, Lamar discusses violence, oppression, and music in black America.

Upon first listen, the album can seem overwhelming. Ideas are jumbled, and Lamar even contradicts himself during several songs. However, it’s his contradiction, his uncertainty, and his uniquely observant approach to race issues that makes the project so memorable. “To Pimp a Butterfly” may not satisfy party-goers yearning for club hits, but it is undoubtedly his best piece of music yet that exceeds even the highest expectations for a complete, thematic hip hop album.