I spent many hours slapping various parts of my body in preparation for a history final last year. To remember John Locke’s theory, I pinched my ears. To remember the sequence of the French Revolution, I hit my stomach, then my elbows, then twirled in a circle. And to remember the philosophies of female thinkers of the Enlightenment, well, you can fill in the rest. Why did I do all this? With my weird methods of memorization, I managed to hammer into my body three essay outlines for the prompts that my teacher had given us in advance.

It worked. When the test came, I pictured myself doing my various dance routines and I got a good grade.

What didn’t work, though, was my long term understanding of the content. Today, if you asked me the sequence of the French Revolution, I couldn’t even tell you who was fighting. And actually, when I wrote that vignette above, I made up what I memorized because I couldn’t remember the details —I just remember putting movements to facts.

My experience is not unique to history and it’s not unique to me. From the analysis of literature to the word problems in math, it seems we approach much of our academics the same way: memorize, regurgitate, repeat. And, of course, forget.

We are so focused on achieving that we don’t learn the material.

Often we are blamed for being too grade-driven. Teachers of honors classes tell us we should “be in it for the learning,” while op-eds in the Bark tell us we should live in the moment and not spend so much time trying to get into college.

Indeed, it is a burden to spend so much time worrying that our grades won’t be good enough and our test scores won’t be high enough. But it is foolish to think that we can simply forget our grade woes and immerse ourselves in the joys of learning when our very education system demands the opposite.

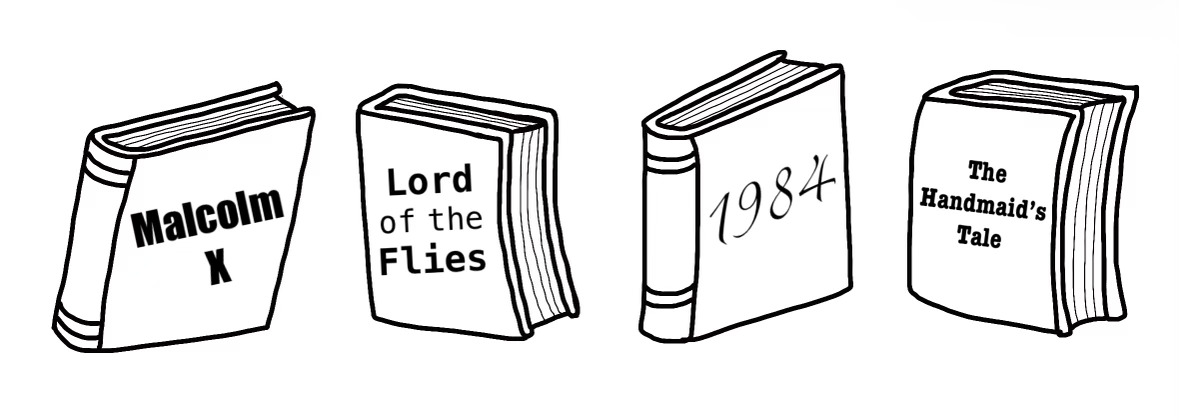

Education psychology research makes clear that when people are focused on achievement, they don’t learn as well. A study by Clark University professor Wendy Grolnick, PhD, and University of Rochester professor Richard Ryan, PhD, found that students who were told they would be graded on a social studies lesson had more difficulty understanding the text than their counterparts who were told they wouldn’t be graded.

A week later, the students who were graded experienced “a greater deterioration in rote learning” than their counterparts, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information. In other words, not only did the students who were graded not understand the material as well, but they couldn’t remember it as well either.

Furthermore, when we are graded, our motivation to learn is crushed. We are taught to focus on the the final product—whether it be a letter grade or a number on the proficiency scale—instead of the process of getting there. We come to believe that learning itself is second in importance to doing well, and that achieving matters more than understanding.

“Every study that has ever investigated the impact on intrinsic motivation of receiving grades (or instructions that emphasize the importance of getting good grades) has found a negative effect,” writes education author Alfie Kohn in his article “The Case Against Grades.”

Often we are told the school cannot get rid of grades because students would not fare well in college admissions. Yet this notion is simply not substantiated. Other high schools have already ditched the grading scale and their students continue to be accepted even to the elitist of universities.

Saint Ann’s High School in New York, for example, has the highest percentage of students of any high school go on to Ivy Leagues, according to a Wall Street Journal article. And they don’t give their students letter grades.

The Tam district claims to be “dedicated to the development of creative, passionate, and self-motivated learners,” as written in the mission statement. Yet it has designed a system that achieves just the opposite.

If we are to become truly motivated learners, we should receive written feedback and qualitative criticism instead of letter grades. Only then can we focus on understanding instead of achievement.