Keith Haring began his artistic career in New York City subway stations in the early 80s. He used chalk to draw on empty advertising panels on the station walls, working quickly so he wouldn’t get caught.

Now, Haring’s subway drawings are, somewhat incongruously, in a museum. The DeYoung Museum in San Francisco, to be more specific.

The subway drawings, and much of Haring’s other work, are featured at the DeYoung until Feb. 16. The exhibition, “Keith Haring: The Political Line,” is the first West Coast show of Haring’s work in decades. It does justice to Haring’s legacy, highlighting the political issues that he fought for.

Haring, who rose to prominence during the 80s, was a huge contributor to the social activist culture. His style is somewhere between graffiti and cartoon, and his brightly-colored paintings are easily recognizable and widely pleasing.

The paintings are most impressive when seen in person. Haring painted on big canvases with big, broad brushstrokes, which has a powerful effect. His subjects don’t have detailed faces, or any faces at all—they’re just colorful outlines, but they dance and move and exude a unique energy.

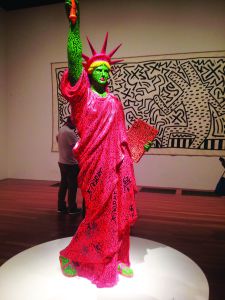

The exhibit is interesting from start to finish, partly because of the variety of mediums that Haring painted on. As you walk up to the first gallery, a neon-colored Statue of Liberty greets you at the entrance. Upon closer inspection, you see that Lady Liberty is covered in patterns drawn in pen, stretching from the top of her torch to the bottom of her robe.

There’s also a crumpled taxi hood covered with patterns drawn in marker, and two towering totem pole-like sculptures. There are huge canvas tarps, covered with intricate designs, that take up entire gallery walls.

Each room in the DeYoung’s exhibit focuses on a different topic: capitalism, Apartheid, the environment. Haring was an outspoken advocate for a variety of causes, as evidenced by the range of issues that his art focuses on. There’s a short written explanation about Haring’s interest in the issue, then the art tells the rest of the story.

The political messages conveyed through Haring’s work are powerful. His use of simple outlines and primary colors just serves to accentuate his point—though his paintings seem conceptually basic, they contain meaningful messages.

I enjoyed the setup of the exhibit, since it placed emphasis on each of Haring’s activist causes instead of trying to lump all of them together. In this way, I was able to really learn what the artist stood for.

But because the focus of the exhibition was on political activism, it didn’t place as much emphasis on other parts of Haring’s identity. Haring, who was gay, died at age 31 at the height of the AIDS epidemic, and much of his art reflects this part of his life.

Haring’s art is often focused on sexuality, albeit in an abstract way—remember, his human figures are just outlines. However, I felt that the exhibit glossed over this side of Haring, focusing more on his politics.

I was pleased that Haring’s work was quite accessible—it seems that anyone, no matter how much or how little they know about art, can enjoy it. I’m not an art expert by any stretch of the imagination, yet I enjoyed Haring’s inventive style.

It takes around 30 to 45 minutes to walk through the exhibit—maybe longer, since you could easily start staring at a painting and become hypnotized by the complex patterns and vivid colors.

There’s an audio tour of the exhibit available for an extra six dollars. I opted against it, and found that I was still able to get a feel for Haring’s work. Tickets for the exhibit cost $16 on weekdays and $19 on weekends and holidays, and they’re well worth the price.