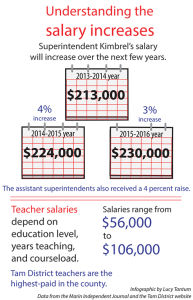

A lengthy debate arose at the Tam Union High School District board meeting on Tuesday, Nov. 18, concerning the raises of three contracted administrators. Laurie Kimbrel, Lori Parrish, and Michael McDowell received new contracts for the 2014-2015 year, which gave them a four percent raise and a one percent bonus.

School board president Bob Walter argued for these raises, stating that McDowell, Parrish, and Kimbrel deserve the raise because of all the good work they’ve done for the district.

“Any way you look at it objectively, the district is doing really well. It’s with these folks leading it,” Walter said.

Walter stated that Parrish, McDowell, and Kimbrel are moving the district forward and helping the students.

“How do we tell if a student does or doesn’t know what they need to, or how do we challenge them or help them gain mastery? All of this has happened on the academic and curriculum success under the watch of these leaders. They’re moving the district forward on the curriculum side,” Walter said.

Nov. 18 was the second board meeting at which these raises were debated. The first, on Oct. 28, was disallowed because of a violation of the Brown Act, a California act that states that the public must be able to attend and take part in in local legislative meetings, such as the school board meetings.

The board was called out for not allowing public comment before approving the consent agenda at the start of the Oct. 28 meeting, which included the new contracted administrative salaries. They contacted their lawyer during the meeting, who advised the board to revote on the items after allowing a public comment period.

However, Linda Ross, a lawyer and parent of a student in the district, argued that it was unfair if the board revoted because many of those who had wished to comment had already left.

“Even if you do vote now and approve the consent agenda, it’s going to be void and it’s going to be illegal to pay people those higher salaries until you do it right,” Ross said at the Oct. 28 board meeting.

In response, the board postponed the voting until the next meeting on Nov. 18.

“Because some of the people had come there to criticize the raises, we decided it wouldn’t be fair to them,” Walter said. “We pulled those items off the consent agenda, and said we would bring them to the next meeting. We’ve never had an issue with contract adjustments. I screwed up at the beginning of the meeting and tried to fix it and moved it to the next meeting.”

According to the Governance Handbook, which states governance roles and processes, the board is required to be completely transparent. At the meetings on Oct. 28 and Nov. 18, however, there were several unsubstantiated claims that the board was discussing public information in closed sessions.

Closed sessions occur at the start of each board meeting, and are closed to the public. They address confidential and personnel matters, along with legal topics like lawsuits or real estate negotiations.

According to Walter, many opponents to the raises didn’t understand what an appropriate salary was for the administration. To address this problem, the board went over the typical salaries other schools receive.

“One board member took salaries from comparable counties and in all cases, our superintendent salaries are by no means at the top. They are well in the middle. We were by no means at the top for per-pupil rate,” Walter said.

According to Walter, up until Oct. 28, nobody had vocalized their desire to give their opinions on the consent agenda.

“I didn’t know that I was supposed to allow comment before we voted,” Walter said.

Walter stated that he and the other board members were only doing their job and that the mistake he made of not allowing public comment should not affect the merit of administrators receiving a raise.

According to student trustee Jessica Flaum, much of the controversy came from the inability of those in attendance to have their voices heard. When Ross attempted to bring attention to the lack of public comment during the original consent agenda vote on Oct. 28, she was called out of order.

“People tried to speak out about it and they were denied allowance of public comment. That’s what I think really sparked the outrage,” Flaum said.