Less than a minute after Principal Sondheim announced that the school was under lockdown, students in my sixth period math class pulled out their phones and began their attempts to find out what was actually going on.

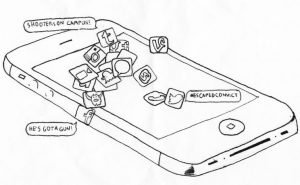

Texts came in 50 spurts at a time, and unsubstantiated rumors surfaced in each group chat. My mother heard that there was a San Quentin escapee. My friend in the art building heard screaming and thought there were two shooters on campus.

My cheer team rattled off final goodbyes via group chat, punctuated by reports from a class where the police came into the room and instructed everyone to put their hands on their desks. Rumors swept through the quiet halls, and even though we were told to be silent, we whispered incoming news that we heard from friends around the campus.

Now that the lockdown is in the past, I’ve come to realize that it was a morality test in who would, or could, refrain from spreading rumors. As soon as the threat of danger came upon us, we came up with a way to explain it.

Rumors are born out of a need to know what is going on around us, and even if that knowledge is only partially correct, we often accept it without pause. This ferocious appetite for rumors teeters dangerously on the edge of reason, often justified.

Using snippets of information learned via text and the Twitter feed, students tried to answer the frenzied questions from parents. We relayed false information from the distorted stories sent to us by peers, which created a venomous cycle of bias and uncertainty common in daily life.

During the lockdown, for the first time, our entire school was out of the loop. In the face of uncertainty, we fabricated our own answers over our tiny glowing screens, unsure which version of the story was correct.

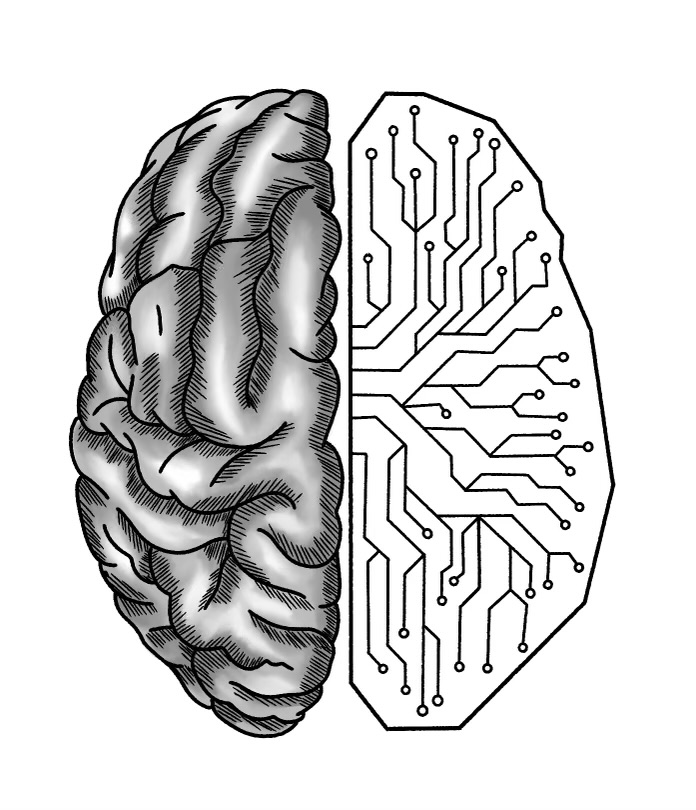

The study shows that under pressure, the teenage brain gets even worse at decision-making, and is more likely to take risks, which could explain such as the massive amount of poorly made rumors spread during the lockdown.

A 2013 study done by researchers at NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health showed that the prefrontal cortex, the portion of the brain responsible for decision making and rational thinking, isn’t fully developed until age 25.

It’s not only during stressful situations that we jump to conclusions or completely fabricate events. Everyday, walking through the halls at Redwood, I hear and see people spreading information faster than they can accurately verify it. With phones only inches away from our fingertips, and apps that spread short snippets quickly and anonymously, rumors are easier to transmit than ever.

We live in the “Information Age.” With everything from the 234th digit of pi to Queen Elizabeth’s height readily available within seconds, it can be hard for our generation to deal with the unknown and resist the urge to disseminate falsehood. Given our experience with the lockdown, we must take note that it remains important to learn how to be at peace with the unknowable and refrain from aggressively attempting to fill in the blanks with both true and false information.