Before I knew what a republic was, I knew how to pledge allegiance to the American flag and to the republic for which it stands.

From the first time I recited The Pledge of Allegiance in kindergarten to when I read my economics textbook last week, my education has directed me to favor America, by saying how amazingly free we are while glossing over the accomplishments of those who are underrepresented in our society.

A fair portion of what I learned in my high school U.S. History class revolved around white people. Our study of the Gilded Age focused on white prosperity and political corruption, with minor mentions of the influx of immigrants. Our textbook focused even less on the grueling labor of those many immigrants who worked to build the railroads that led to prosperity.

The current curriculum for Redwood’s U.S. History classes focuses far too little on people of color and should be changed to accurately reflect the numerous contributions that people of color have made to American history.

There was only one time in the entire year where we learned about more than five people of color in a unit. It was a civil rights unit that, by virtue, included many prominent people of color.

Prior to that civil rights unit, my class had only learned about two people of color in America in our other units: W.E.B. Du Bois and Thurgood Marshall.

In my junior year history class, we began our study of American history right after the Civil War. We covered more than 100 years of history, and yet only two leaders of color were featured in the curriculum.

This discrepancy is too high. There were many notable figures of color during those times that we could have learned about. One of those people is Ida Wells, a prominent anti-lynching leader, suffragist, journalist, and speaker responsible for documenting many of the horrors committed against black Americans in the South during the progressive era. Charles Drew is another; he discovered the modern process for preserving blood for transfusions during World War II.

Native, Latino, and Asian figures are nearly nonexistent in the curriculum until the class reaches the social reforms of the 1960’s. Before that, the only mention of any of these groups, let alone named individuals, was in passing, while talking about the immigration boom in the early 1900’s.

Japanese Americans were also briefly mentioned in our study of the World War II internment camps (one of the only unsavory aspects my history class touched on), but made no specific references to people interned within the camps.

We learned about the outcome of court case of Korematsu v. United States, but never talked about Fred Korematsu as a person.

The only Latino person we learned about throughout the year was Cesar Chavez. We could have learned about Dr. Hector Garcia, who held meetings for Mexican Americans to voice their concerns following World War II. These meetings sparked a movement that led to the creation of the American GI Forum.

Since American history focuses deeply on America, the curriculum should reflect an accurate cross-section of the population. Native, Latino, and Asian people were each present in the United States between the Gilded Age and WWII. By hardly mentioning any of these groups, we erase them from history. By largely ignoring these groups, students aren’t exposed to an accurate snapshot of a time period in America.

Through analyzing the past, it’s easier to understand how and why certain things are the way they are: why the USSR collapsed and how Russia has interacted with the world since, why tensions in Korea are still high, how the world has managed to avoid a World War III thus far.

By learning what went wrong, we can hopefully learn what to do right going forward. But if information isn’t presented accurately from a time period, then our ability to draw realistic conclusions and form an accurate view of the world is compromised.

My motivation to learn and enjoy history has been deterred by the fact that I never know if I’m being told every angle of the story. The fact that my education revolves around a prescribed curriculum that does not show all of the facts certainly doesn’t excite my desire to deepen my understanding.

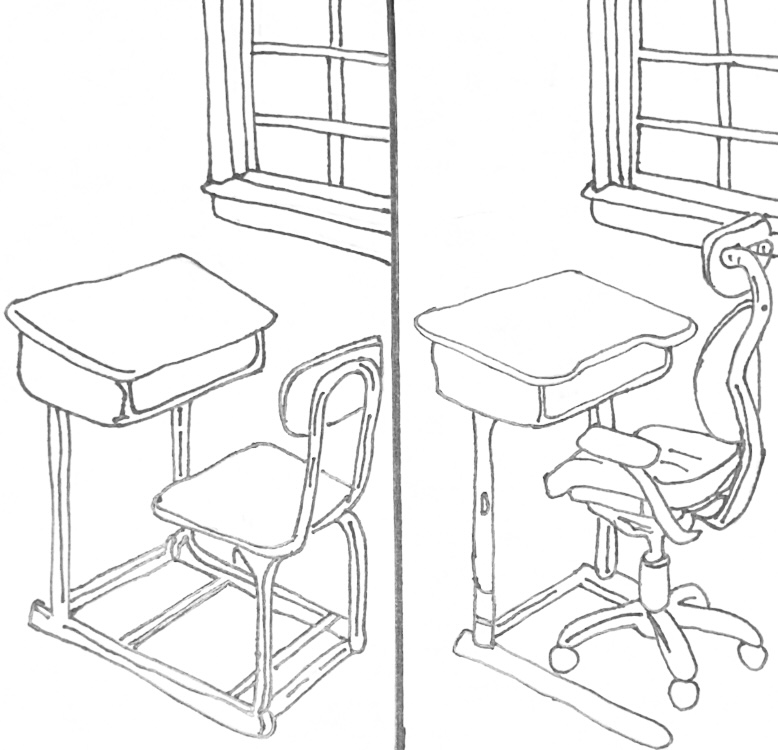

Of course, the scope of what the curriculum lacks isn’t entirely the fault of teachers.

There are certain requirements to which U.S. History teachers must adhere, and it is the responsibility of the teacher to supplement what the core lacks. While education is the responsibility of both student and teacher, students don’t choose what they’re being taught. It’s up to the teacher to assure complete accuracy to better inform and teach their students.

American students deserve to hear the truths about their country, including all of the unsavory information leading to the present.