A few days ago, as I was walking through the halls, I ran across a group of freshman boys who, by the look of their incessant shouting and high-fiving, had just been met with some success on a recent test. They all clung to each other with a jubilant fervor, joking and guffawing without a care in the world. I smiled at the act, and found myself drawn continually closer to their conversation until, quite jarringly, I heard the inevitable.

“I raped it, bro.”

I foundered, confused and disturbed by the comment, and found myself almost numbed with sensitivity. It was an expression I had heard from the mouths of upperclassmen too often. Hearing it from one younger than me, however insignificant our age gap was in actuality, disturbed me to the core. In the spur of the moment, I calmed down by convincing myself that the boy didn’t really understand the true significance of what he had said and that I was just being my overly-sensitive self.

A few days later found me still pondering the hallway outburst. In that span of time, I heard the word “rape” used 17 times in casual conversation, and each time I added to my mental tally with a twist of my stomach and a clouded mind.

Why now was this word causing me so much anxiety and pain? It hadn’t bothered me freshman year when, after watching a video on self-defense, the members of my class began to yell the word whenever someone snuck up on them. It had barely fazed me when a good friend of mine took to toting his accomplishments as “raping this” or “raping that,” barely caused a disturbance when, at a school dance, I overheard an older girl say that her friend looked as though she was “asking to be raped.”

It finally hit me during lunch hour. I was walking near the front of the school when I heard the word screamed violently from a nearby senior, inciting a wave of laughter from his surrounding friends.

I took particular interest in one member of the group, being that she was the only female, and observed her to see what her reaction would be. A first glance might suggest that she found the comment equally as funny, if not more so, than her male counterparts. Then I caught for a moment a violent change in her expression, a noticeable cringe that demonstrated quite clearly her displeasure with the comment. It was gone after a moment, but her laughter seemed hollow afterward.

I in no way mean to suggest that this young woman had experienced the horrors of rape or knew someone who did. For all I know, rape could seem to her as it seems to many of us: an act heard of only in crime shows or on the news. But her reaction suggested to me something more about the use of the word and its assimilation into our common vocabulary.

Saying “rape,” no matter what the context, only serves to make it more prevalent in our society. Mix this constantly verbalized message with our extremely sexualized culture and a steady stream of easily accessible internet pornography and suddenly what was once an inappropriate word becomes something very, very real.

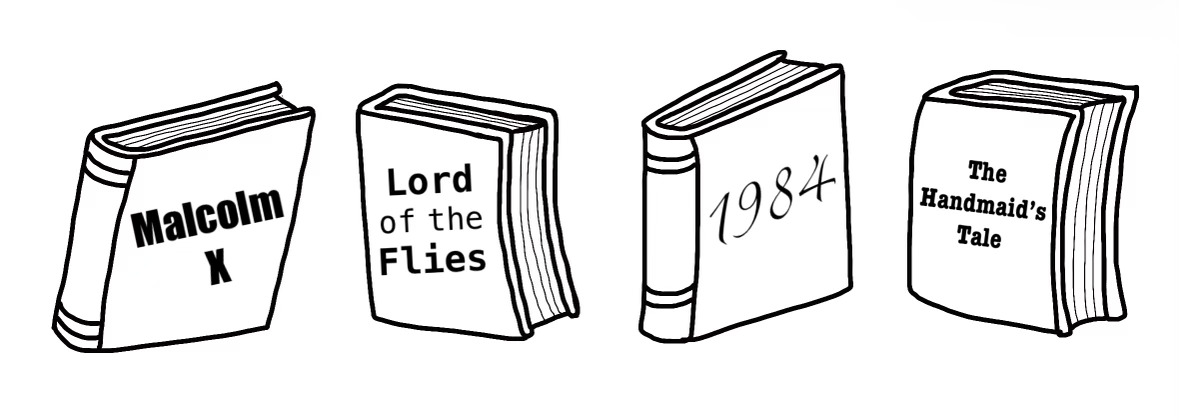

Take, as an example, Charlize Theron’s use of the word in a recent response to a question about Googling herself: “I don’t do that. When you start living in that world, and doing that, you start, I guess, feeling raped.” As a prominent public figure, Theron’s comments succeed only in normalizing the use of “rape” in everyday jargon. If Charlize can say it, why can’t we? The more we say the word “rape,” the more we desensitize ourselves to its potency, and the more we come to treat its use as something culturally acceptable.

So no, it’s not okay and no, you weren’t “just joking.” The word “rape” and any other social connotations that come along with it serve only as cheap substitutes for an infinitely better bank of words and expressions. Drop the lingo and leave it alone. It’s the last thing we need as a cultural norm.