I’ve been telling people that I want to be an author when I grow up since the fourth grade when, instead of doing daily journal entries, I compiled a 140 page story about an astronaut whose ship veers sharply off course and crash lands on a planet governed by warring anthropomorphic superpowers. Writing a book was never something I set out to do, merely an inevitable accumulation of my efforts.

Nowadays, it’s easier than ever to publish a book. As of a few weekends ago, I joined the self-publishing inundation by making my first book available for purchase on Amazon – an intimidating process that I successfully navigated within an hour. I hope that this lexical foray shall be the first of many. However, in light of the literary climate of our time, I also recognize that the prospect of profitability or even breaking even is increasingly bleak in this avenue of employment.

It is increasingly popular these days to be a doomsayer – to take a limited sampling of an evident trend and brand it a harbinger to the ending of society as we know it. Recently, scholars have cited the prevalence of screens in our generation’s everyday life as evidence that we do not read, and therefore, all subsequent generations shall be doomed to wallow in a self-inflicted gloom of ignorance and illiteracy.

In respect to these woes, I firmly believe that we are not illiterate. On the contrary, by supplementing assigned reading with Internet reading, our text comprehension is better than the elder generations who presume to prescribe our doom. There is, however, a fundamental and worrying difference in our motivation for reading. If nothing else of merit, studies have shown that our generation has abandoned reading as source of entertainment. We are capable of reading; we just don’t want to.

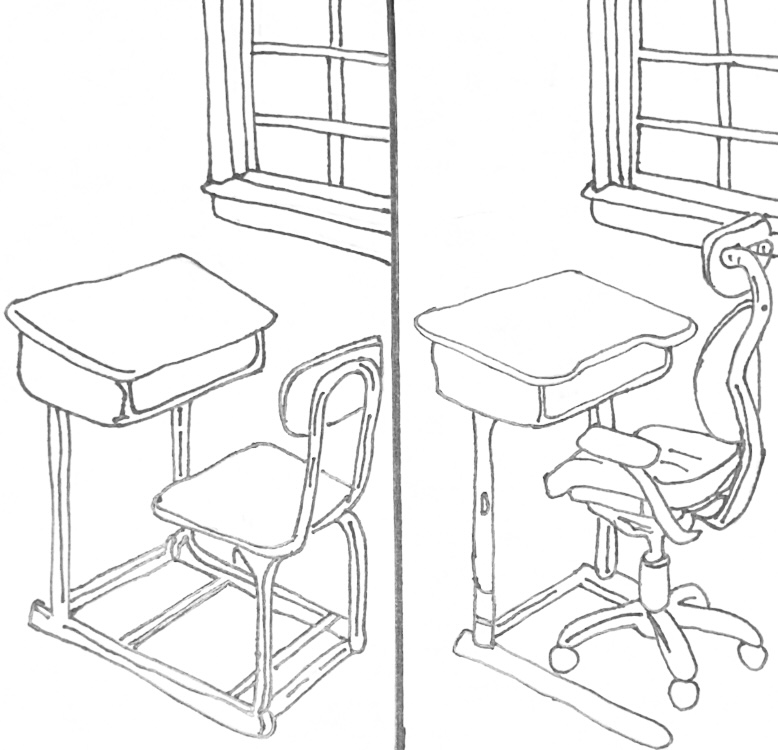

Although I wouldn’t willingly stigmatize ourselves as the “illiterate generation,” I would venture to call us “the instant gratification generation,” – a penchant that marketers and modern-day artists fall back on when ingenuity or creativity fails them. It’s difficult to write a poignant script with clever dialogue, but it’s comparatively easy to dazzle viewers with a shot of Captain America somersaulting over an enemy in slow-motion while New York City crumbles behind him – in 3D. This is not to say that all entertainment today is thoughtless.

Every year, Hollywood makes about five films that are intellectually rewarding and substantive – but these do little to redeem the multitude of recycled “thrillers,” that we have all seen – a characteristically fast-paced romp through a post-apocalyptic city that clings to humanity by enticing viewer’s with a predictable subplot of forbidden love. It’s easy to detach oneself from this lowest common denominator form of entertainment, but, adhering to the laws of basic economics, these movies also sell the most tickets.

Authors too have stumbled upon a similar approach to their craft. A century ago, there were prose writers who refined the lucidity and poetry of their words, crafting not plot, but introspection. Today, this is considered an archaic approach – dissembled by an audience with an appetite for familiar plotlines. People read nowadays, yes, but only what is expected of them – what everyone else is reading. We all read The Hunger Games, and Harry Potter, but few, if any of us take a chance on a new book we’ve never heard before, one not based on a movie (chicken or the egg?). This selectivity has created a very limited market. True enough, best-selling authors with extravagant marketing campaigns, who, often, run a talk show in their spare time, have been untouched by America’s collective resignation of reading as a hobby. But the underdog, the stalwart who writes by lamplight at one in the morning, coaxed by the ecstasy of their ardor into another exhausted day at the office, the undiscovered author, shall, inevitably, remain undiscovered.

This problem is not our fault entirely, however, our apathetic approach to modern literature serves as a crucible for the present climate of the book market – already so exclusive, yet rendered almost hermetic by a declining demand for reading material. Posterity needs us to change our mind if art is to continue to develop, if we are to resuscitate books and bookmakers alike.