More than 50 years ago, the United States severed diplomatic ties with Cuba, creating a political and cultural rift that still exists to this day. Yet, when a government facility in Havana opened its gates to my high school baseball team last week, the international tension surrounding our baseball team’s trip to Cuba was nowhere to be found. Instead, the ringing sound of bat on ball pierced the run-down streets of Cuba’s capital city, reminding the people of the type of American contact that was absent on the island.

Our road to Cuba and the Dominican Republic was riddled with bumps along the way. First, Texas Senator Ted Cruz publicly insulted Cuba, leading the Cuban government to cancel our official games in their country. The entire trip, nearly a year in the making, was in jeopardy.

But quick improvisation from our group organizer Manny Kopstein solved the problem, at least for the time being. We booked a flight to the Dominican Republic, where we would play four games in three days against some of the best teenage ball players in the world.

Just as it looked like everything was in place for a smooth and hiccup-free trip, the pilot in San Francisco didn’t show up for our flight.

The cancelled departure was only the beginning of our traveling woes: We had to spend the first night in Houston at a hotel with bloodstained sheets; in Cancun, we missed our connecting flight to Havana, a flight that only runs once per day; the next day, five members of the group were left in Cancun for another night because of limited seat availability on the plane; and, when it looked like the flying situation couldn’t get any worse, two members of the group were stranded in Cancun for yet another night after the flight attendant informed them that there were only three seats left on the plane. All in all, it took over four days for the whole team–and the 650 pounds of donation items–to be united in Cuba under one roof.

Exhaustion. Fatigue. Doubts about the trip. All of these were diminished when we stepped out of our team bus in Havana, and had completely vanished by the time we had finished donating 45 pounds of medicine to a local synagogue later that day.

I could see the facial expressions of the team change as we observed everyday Cuban life. We saw how people who lived in run-down neighborhoods–most of whom lived off of $10 every month–managed to maintain a happiness in their lives that permeated through their poor living conditions.

One face that I will never forget is the face of Ryder–a third basemen in his mid-20s on an opposing Cuban team–as I asked him if he had ever been to the United States.

“To go to the United States,” Ryder said in a somber tone, “is my dream. The American Dream.”

We left Cuba with a better understanding of what this dream meant to many who had never experienced economic freedom, and moved on to the Dominican Republic with only a few remaining donation bags. The majority of the 1,510 donation items had stayed in Cuba. Baseball bats, balls, catcher’s equipment, helmets, jerseys, and more were distributed to children hoping to be the next Puig or Cespedes of their generation.

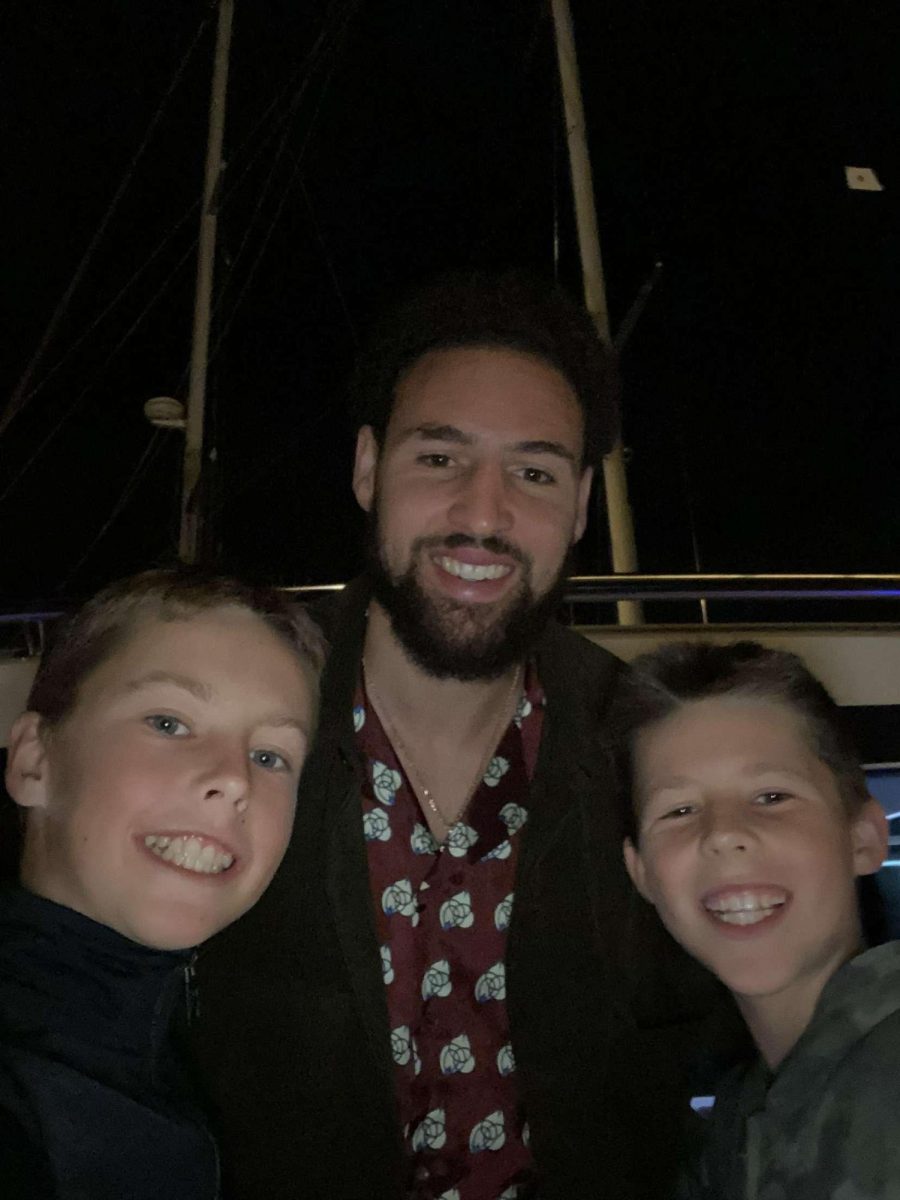

But if Cuba represents a tasty hamburger, then the Dominican Republic is the filet mignon of baseball. Their process of training young talent runs like a well-oiled machine, evidenced by last year’s World Baseball Classic victory.

Cuba has sent nearly 200 players to the MLB, a staggering number for such a small and underdeveloped country. The Dominican Republic, despite being half the size of Cuba, has sent almost 600.

The Dominicans’ technical prowess and natural ability were clear on the baseball diamond. Anyone spectating either of our games in the town of San Pedro would have picked the Dominicans as an easy favorite over us Americans. Athletically superior and nearly semi-professional players sat on the “Home” side, while a combination of small varsity, JV, and freshman players–a group that had never played together before–sat in the “Visitors” section. On top of our obvious athletic inferiority, our team also had to deal with two injured players and one more vomiting on the side of the field.

Nevertheless, we beat the local San Pedro team in a 7-6 nail-biter on a pothole-filled field with no dugouts or fences. We immediately drove to a 1990’s Chicago Cubs facility where we faced the most difficult obstacle of our entire trip.

Sick and tired, our team had to gather the strength to play against San Pedro Academy, which featured at least three players that had signed to Major League ball clubs, and fireballers who threw in the 90-92 mph range.

We started our ace, sophomore Zach Cohen, who struck out five batters in three scoreless innings. We scrapped together one run in the third inning, played solid defense in the later innings, and junior Nate Flax closed out the 1-0 victory with a stellar pitching performance.

Not only did we catch the attention of the spectators, but we also proved many of their preconceived notions incorrect. More importantly, we gained their respect.

After 10 days abroad in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, we returned home with a 4-2 record, and many preconceived notions of our own that proved to be false.

Sometimes, political drama can distract from the issues at heart, and our team witnessed firsthand how one political figure’s actions can have wide-ranging effects. But behind all the feuding between the United States and Cuba lies the shared love of baseball, a game that has prevailed throughout sanctions and trade embargos.

Hopefully, the two countries can move toward a more open policy towards each other–one more representative of the red, white, and blue that they share on their national flags.