Marin’s environmental equity problem

December 9, 2022

“We (Marin City residents) are living fewer years than folks on the left [of Marin City]. We’re living fewer years than folks on the right [of our city]. We’re living fewer years than folks up the street. Call your Supervisors. Call your politicians,” Terrie Green, Executive Director of Marin City Climate Resilience and Health Justice, said at a “walk-a-thon” event at George Rocky Graham Park.

This push for change was motivated by the disproportionate impact that climate change has on the lives of Marin City residents. Since Marin City is unprotected and directly adjacent to Highway 101, it is constantly exposed to both air and water pollution from the freeway. Additionally, there is rising concern about backed up air vapor in pipes at multiple decommissioned contaminated sites and dilapidated infrastructure, making the area more prone to flooding. All of these environmental hurdles decrease the lifespan of residents.

According to Green, Marin City residents have a life expectancy that is 20 years shorter than in surrounding areas. Marin City also has both the highest chronic disease rate and disability rate in all of Marin County. The health issues that this community faces are unjust considering that Marin County as a whole was ranked the healthiest county in California in 2022.

According to Marin City Climate Resilience and Health Justice, Marin City falls in the 35th percentile of CalEnviroScreen 4.0, which identifies California communities that are disproportionately affected by pollution. This number is far higher than the rest of Marin County, which falls between the fifth and 10th percentiles.

Aware of this clear disparity, senior Hannah Knopping claims that climate injustice in Marin does not get enough attention. Knopping recently attended the Bay Area Youth Climate Summit, where she learned more about discrepancies in Marin City.

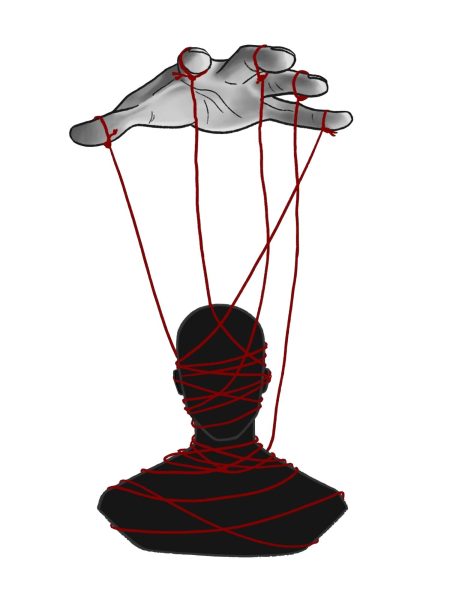

“Unfortunately, people aren’t very aware of the situation in Marin City. Marin City has been neglected, and the people there are left incredibly vulnerable to climate change. There is a clear connection to systemic issues in our country, like racism and wealth inequality. People of color and those of low socioeconomic status are being impacted disproportionately by the consequences of climate change,” Knopping said.

Knopping notes that affluent people contribute significantly more to the climate crisis compared to those of lower-income.

This is even more disturbing when you realize that it is the wealthy that are the primary contributors to climate change, while the disadvantaged face the repercussions.

— Hannah Knopping

“This is even more disturbing when you realize that it is the wealthy that are the primary contributors to climate change, while the disadvantaged face the repercussions,” Knopping said.

According to Advanced Placement (AP) Environmental Science teacher, Kelsey Kniesche, wealthier areas in Marin tend to have a larger footprint, while areas such as Marin City are left vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

“We all play a role [in climate change], but more affluent areas [tend to be] the [largest] polluters, especially based on our [high] resource consumption,” Kniesche said.

Kniesche explained that Marin City residents are not equipped to protect themselves from ever-changing and worsening climate conditions.

“There are great inequities when it comes to planning and implementation strategies to protect against impacts of climate change. Resources have been allocated to specific areas within Marin, [but are lacking in areas such as] Marin City,” Kniesche said.

Kniesche notes that there is outdated infrastructure in Marin City, exacerbating the community’s struggles.

“[Marin City] still has pipes set up that are over 50 years old; they are lead-based and cracked. [Residents are] exposed to pollutants and contaminants. When there’s flooding, we see that there is exposure to contaminated water, especially with one road that is very easily flooded during high tides or when we have those atmospheric river storms.” Kniesche said.

These lasting problems leave the residents of Marin City, who are more likely to be people of color than anywhere else in Marin, vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Kniesche suspects that systemic racist policies such as redlining — a discriminatory practice that makes vital services unavailable to people of color — are the root of these inequities.

“Redlining [and poor] treatment of indigenous peoples [have] all [occurred] in Marin. After World War II, [Marin City] was a redlined district, where people of color and low [socioeconomic] status were grouped into that one area. [Residents of Marin City also] didn’t have much of a voice within the community and decision-making.” Kniesche said.

Due to redlining, this community was one of the only areas in Marin where African-Americans could live after the war. The effects of this discrimination are still apparent today. As a county, Marin currently ranks second in racial inequity in California, according to the Advancement Project California. Marin City remains almost 40 percent African-American and has a median household income of $40,000, both significant contrasts from the rest of Marin.

However, this problem is not exclusive to Marin County. Carly Lam, Community Conservation Fellow at Audubon, is passionate about environmental injustice and views it on a broader scale.

“A common trend is that people of color and low-income communities tend to have less access to nature,” Lam said.

Lam believes that all environmental issues are different, and there is no single action that will fix this incredibly complex and pervasive problem. Instead, she concludes that the solutions need to be localized.

“The solutions need to come from the communities that are being impacted. It cannot be a one size fits all solution,” Lam said.

Lam wants to see community leaders play a bigger role in solving the problem.

“Giving power and a voice to the communities that are impacted by environmental injustice is one of the first steps that need to happen. People are doing work within their own communities and they need more support,” Lam said.

Green had a similar proposal in a presentation about a possible localized solution in Marin City.

The world is going to have to know what’s happening for change to come about. Let’s fix it.

— Terrie Green

“We need new pipes. We need drainage pipes and a drainage system. We need infrastructure investment in Marin City. We need contaminated water and sediment removed. We need protection from toxic harm,” Green said. “The world is going to have to know what’s happening for change to come about. Let’s fix it.”