The Troubled Teen Industry: Utah’s dark side

March 3, 2022

Utah, a state characterized by its natural beauty and preserves, has always maintained a national presence for tourism. Its five national parks and 46 state parks hold picturesque panoramas and wildlife rivaling those of the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone. People flock to the landscape, hoping to see colossal stone arches, ski on white mountain peaks or enjoy riveting white water rafting. That being said, Utah carries a dark secret that has only recently received national attention; over the past half-century, Utah has become the epicenter of what is now known as the “troubled teen industry.”

Gaining significant notoriety in Paris Hilton’s 2020 documentary, “This Is Paris,” the troubled teen industry is a network of rehabilitation facilities that attempt to provide their services to young people struggling with addiction and mental health. While the troubled teen industry is not confined to Utah, it has been able to thrive there due to under regulation and limited oversight. On a surface level and through advertisement, these facilities offer programs that seem to have good intentions in mind. However, they have come under intense scrutiny in recent years due to their business models and alleged treatment of participants. Dr. Amira Mostafa, head of Special Education for the Tamalpais Union High School District (TUHSD), shares many concerns over the ethics of these programs.

“This is a very, very, very lucrative business. [It is] a big business model with lots of arms, preying on that vulnerability of well-meaning families, parents, students and districts, and it turns into a multi billion dollar industry,” Mostafa said. “I have placed students at these residential facilities, but very few and far between.”

Getting a glimpse into the day-to-day operations of these facilities is difficult, however the comments from participants as well as numerous investigations paint a picture of a tumultuous experience. A former Redwood and current Terra Linda student, who has asked to remain anonymous and will be referred to as “Richard,” attended Second Nature Wilderness Program in Duchesne, Utah, during the summer of his freshman year. He described his arrival at the program as similar to that of a kidnapping.

“I was woken up in the middle of the night, confused and scared. My parents were standing in the corner of the room, and these guys came in. My parents didn’t even say anything,” Richard said. “[The men] came in, and they just took me out of my room. I was screaming and fighting back against them. But, I was a little kid; I couldn’t really do anything. They brought me into a minivan and took me to the airport.”

Feeling blindsided and left out of the conversation, Richard described a tattered relationship with his parents thereafter.

“I lost a massive amount of trust with my parents. I felt like they betrayed me,” Richard said. “I wish they just talked to me about it before or came to an agreement with me on something reasonable. It really, really affected our relationship. It broke that trust, and trust is lost in buckets and earned in drops.”

Taking unwilling students from their homes without any prior knowledge is commonplace among several of these facilities. Many participants, including a former Tamalpais High School (Tam) student, who wishes to remain anonymous and will be referred to as “Julia,” illustrated a similar situation at her wilderness rehab center. Julia attended Aspiro Wilderness Adventure Therapy (Aspiro) in Sandy, Utah, and had paralleling sentiments to that of Richard regarding how she was taken to the facility.

Taking unwilling students from their homes without any prior knowledge is commonplace among several of these facilities. Many participants, including a former Tamalpais High School (Tam) student, who wishes to remain anonymous and will be referred to as “Julia,” illustrated a similar situation at her wilderness rehab center. Julia attended Aspiro Wilderness Adventure Therapy (Aspiro) in Sandy, Utah, and had paralleling sentiments to that of Richard regarding how she was taken to the facility.

Once Julia arrived, the program only provided her with more traumatic memories. Lugging 40-pound backpacks, her group walked from six to eight hours almost every day. Julia claims she lost 20 pounds in the course of a month, living off of beans and rice or trail mix for meals. In addition, Julia, who attended due to alcohol abuse and mental health problems, did not find the “therapy” offered by the center to be helpful.

“We had these group therapy sessions once a week; the clinicians would monitor us and our behavior each day, and they would share to the entire group our faults and why we did not deserve to leave. Sometimes it would end in girls crying or arguing, but a lot of times there was victim-blaming, making us feel responsible for our trauma and the bad stuff that has happened to us,” Julia said. “It wasn’t actually therapy; it was just public humiliation.”

With minimal contact with parents and the outside world, Julia was forced to bond with the girls at Aspiro. Over the three months at the facility, she became close with the other nine girls in her program, finding her family away from home as well as a source of comfort.

“We basically became sisters. We argued all the time but we also looked out for one another and spent all of our time together. And because of how rough it was, we had to depend on each other just to survive. Sometimes it would get so cold at night all ten of us huddled together under a tarp for warmth,” Julia said.

Although Julia befriended those around her and found a strong community, she believed that the overall program was not the right fit for her.

“I think that wilderness therapy is much more about discipline than it is about actual support,” Julia said. “For most of us with mental health issues, [as opposed to behavioral issues, the program] didn’t actually provide treatments which helped the root issue. Because of how extreme it was, I’d really only recommend it for people with extreme behavioral issues like fighting, stealing or doing hard drugs.”

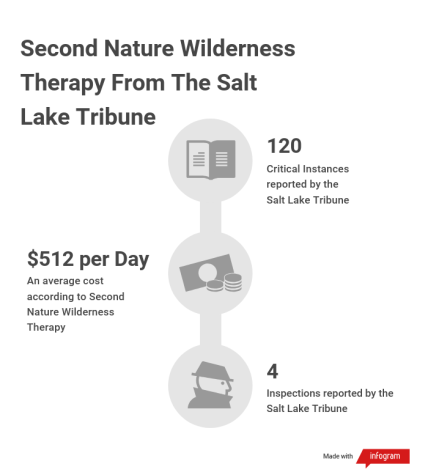

The experiences of Richard and Julia are not outliers compared to others within the system. Many of these facilities are subject to several inspections and critical incident reports by local officials which frequently contain graphic details of sexual and physical abuse, attempted suicides and missing persons. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, Provo Canyon School, one of the largest and highest-earning of these wilderness programs, had the police called on them 55 times by staff in the span of a four-year period for both sex offenses and violent crime. Copper Hills Youth Center, another relatively large facility, had the police called 65 times for similar offenses in that same time period. In fact, because of incidents such as these, the wilderness program Julia attended is now under investigation and being sued for child harassment.

The fact that many of these wilderness programs are often being reported to the police or under investigation, one may be led to believe that all the “bad” programs would be shut down. Brodie Beckham, a Redwood senior currently conducting an Advanced Placement Research project on the troubled teen industry, explains how some facilities are able to remain afloat despite coming under significant scrutiny.

“[In specific instances,] there’s enough complaints or coverage about a certain program [such as North Star Expeditions, that] they’ll close down and then open up another location nearby under a different name,” Beckham said.

From these experiences, it may seem as though parents have little incentive to place their kids in this system; however, many parents feel as though their hand was forced. One such parent, who wished to remain anonymous and will be referred to as “Ryan,” made the decision to place his son in a Utah wilderness center based on concerns of substance abuse and social isolation.

“He’s a very social person and was starting to become very withdrawn,” Ryan said, referring to his son. “He had a lot of anxiety and depression and was starting to abuse substances and alcohol as a way to soothe and self-medicate.”

While aware of the criticisms that had been leveled against such facilities, Ryan remained confident that his son was in the right place.

“If he hadn’t gone to therapy, I think he would be in a really bad place right now. This has given him a second chance and enabled him to address some of his mental health and emotional issues.”

Mostafa, while not putting as much trust in the facilities, did share the notion that enrollment was being driven by a sense of urgency among parents.

“I think that there is a lot of desperation for our parents, unfortunately,” Mostafa said. “You get families who feel like their kids are addicted, and there’s nothing that they can do locally to support them. So they send them away where they think the kid will be away from drugs, peers and influences, believing [their kids] will get cleaned up, get all this mental health care and everything will be fine.”

Marin has a higher drug use than the state average according to a 2020 California Healthy Kids Survey, so it is no surprise that Marin has been particularly targeted by this industry. In addition, the fact that most of these facilities are incredibly costly, with some ranging from $500 to $600 a day, significantly limits their services to affluent communities like Marin.

“The facilities are extraordinarily expensive,” Mostafa said. “In Marin, or in any kind of high-income community with many mental health needs and stressors for students, you are going to have a potentially greater increase in parents with resources to pursue options to address those needs, even if the options are potentially harmful.”

While the troubled teen industry in Utah has been historically underregulated and unchecked, there have been recent attempts at reform. After “This Is Paris” aired in which Hilton described an experience very similar to that of Richard and Julia, she testified before the Utah state judiciary and created a petition calling for the closure of the facility she attended along with several others like it. The petition currently has over 180,000 signatures. Hilton going public with her stories kickstarted a movement called “breaking code silence,” in which attendees would share their stories through various social media platforms, advocating for change within the industry. The movement may have resonated in Salt Lake City. In late March of 2021, Utah Governor Spencer Cox signed a bill that would implement certain restraining tactics, drug treatment and isolation rules, while increasing the number of inspections on certain facilities. It is the first such piece of legislation passed in over 15 years that addresses these wilderness programs.

Even with more awareness and legislative action, this industry is not going away any time soon, and Marin County, and others like it, will continue to be prime targets.

“I would say that right now, I have a lot of kids who are being sent to [these programs],” Mostafa said. “I’m getting kids coming in from the feeder school districts who don’t even walk through Redwood’s door because they’ve been placed [into these institutions] straight out of eighth grade in the summer. So [the participants are] getting younger and younger, particularly coming out of [COVID-19].”

As long as there exists a severe mental health and addiction crisis among young adults, there will be those within the troubled teen industry offering their services and making a profit.

“I think [it is important to make] sure that everybody has done their due diligence and researching while being aware that this is a multibillion-dollar industry and then making an educated decision as a parent,” Mostafa said.

Update: A source has requested a requested a retraction of their name and the Bark staff has granted the request.