Do not wait to join the family debate

December 16, 2021

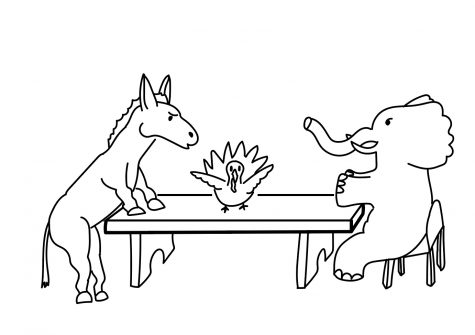

Compliments about the pumpkin pie and childhood stories circulate the family-filled table, until suddenly, the air pressure drops. Inevitably, a controversial political comment has wriggled its way into the once lighthearted conversation. As a teenager, I take this as a cue to sit back and enjoy the free entertainment of intoxicated adults arguing. Part of me wants to chime in, but I stay silent, assuming my age would discredit my contribution. However, silence is not synonymous with civility; in reality, it leaves me feeling disappointed in myself. Respectful debates with family members benefit all involved because they open an insightful dialogue between generations. It is acceptable for teenagers to choose not to participate in these types of conversations, but abstaining should be out of disinterest, not lack of confidence.

Trust me, I know how polarizing it feels to offer the counter argument to your grandfather. “He is wiser than me. He’ll think I’m being an overly-idealistic, politically correct Californian.” When you feel an urge to join the conversation, it is usually for good reason, so speak up. Everyone benefits from hearing new perspectives, political or not, and youth and older generations must help each other understand different values and beliefs. Reading from several newspapers does not inform someone to the same extent as hearing perspectives directly from relatives, because family is easier to sympathize with than a source from the news. The National Academy of Sciences suggests that rationality will not help change a political opponent’s mind; the most effective method of persuasion combines logic with subjective, personal experiences. Because stories enhance arguments, younger generations could enlighten the discussion for older people by sharing their unique experiences. Seth Freeman, a conflict management teacher at Columbia University, warns against using facts and instead recommends the Three Ps: Paraphrase, Praise and Pivot. Essentially, clarify what the debate is about, emphasize where both sides concur, and then offer personal anecdotes. To keep the conversation running smoothly, acknowledge the opponent’s strengths and ask questions to shed light on gray areas.

However, this does not mean abandoning facts altogether. Studies from the Scientific American show that people cling tighter to beliefs when the discussion involves fewer testable facts, such as how someone views a politician or believes in God’s support.

It’s obviously hard to converse about opposing beliefs. According to Pew Research, of people who share political views with almost no one in their family, 28 percent of them say their family is open to discussing politics. Some believe the risk of politics dividing families is too high, but politics do not have to be the dealbreaker in every relationship – people with differing political beliefs can still build connections on a personal level. Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia fell on polar opposites of the political spectrum, but it did not ruin their close friendship of 22 years. Interviews with the two, including one during a 2015 George Washington University event, prove how even the simple pleasures strengthen bonds.

“Call us the odd couple,” Scalia said. “She likes opera, and she’s a very nice person. What’s not to like? Except her views on the law.”

Despite disagreeing over issues of same-sex marriage or gun rights, they learned from each other by revising their opinions. In 1996, Scalia wrote the dissent to Ginsburg; their friendship held out, even after engaging in powerful debate over interpretations of law.

“I disagreed with most of what he said, but I loved the way he said it,” Ginsburg said in 2015.

There are instances where these family conversations do create turmoil, and there are two reasons for this. One: the conversation is not carried out in a respectful, productive way. Failing to clarify definitions, debating facts and demoralizing people’s values will only lead to hurtful tirades. The second comes from values, not politics. A civil debate only breaks up a family when it exposes fundamental differences in morals; the epicenter of earthquakes covered up by the political landscape. Politics sometimes reveal a truth that no one wants to confront, and acknowledging differences is healthier than keeping up the facade of the “perfect” family.

Clearing the plates after dinner, you might feel angry, maybe even disappointed in family members but remember: those emotions will fade. Permanently shutting out the people you love, but sometimes disagree with, wastes energy and demonstrates intolerance. Some families thrive “at an arm’s-length” or “taken in smaller doses,” and this does not make them less of a family. It’s easy to scoff at the argument that family comes before politics, but in actuality, love must come before pride. To raise a generation of peacemakers, children must learn to create atmospheres where everyone feels heard and valued. Young and old must both build this two way street of respect, one that hopefully extends beyond the realm of politics.