The terrifying prospects of a new war on terror

November 3, 2021

John Walker Lindh is a name that Redwood students may recognize. He attended Redwood and Tamiscal, converted to Islam at age 16, studied Arabic in Yemen at age 17 and fought for the Taliban until his capture at age 21. It is important to remember that Lindh joined the Taliban prior to 9/11, and that the intention of many who fought for the Taliban was in reaction to the repressive Northern Alliance, who had not been affiliated with the United States until 9/11. There is little to no evidence that Lindh was involved in any terrorist activity, yet some of America’s most powerful figures suggested as such in assertive public statements. The most emphatic of these statements was former Attorney General John Ashcroft accusig Lindh of direct attacks against the United States despite citing minimal evidence. The so-called “presumption of innocence” that is supposed to be enshrined in the constitution was not upheld at all.

Lindh was only one of the thousands of victims of expanded security measures post-9/11. It started with the infamous Patriot Act passed a mere 45 days after 9/11, expanding the use of National Security Letters and so-called “sneak-and-peek” searches. These measures essentially gave federal agencies permission to conduct search warrants without prior notice, view personal records without a judge’s approval and turn ordinary Americans into suspects. Over time, these terror measures were implemented globally in what became known as the “global war on terror.” What followed was a bevy of United States initiated torture, drone strikes and detention without trial.

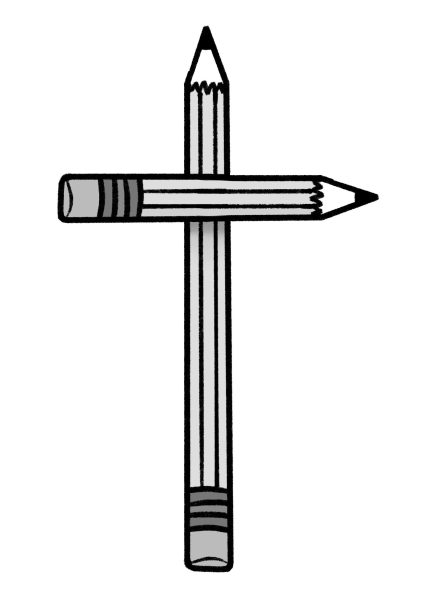

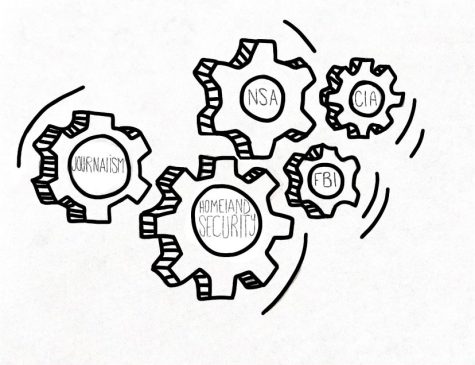

All of this has become common knowledge among many human rights organizations, policymakers and especially journalists. Publications like The Guardian and The Intercept exposed secrets of intelligence agencies at a rate never seen before. Larger publications like The New York Times worked with whistleblowers like Julian Assange to shed light on these war crimes. These kinds of stories may be in distant memory, especially for younger generations, but it’s important to know that when these security measures are implemented, it becomes hard to draw the fine line between common-sense national security measures and intrusive and unconstitutional measures. With this in mind, one would naturally be inclined to reject these measures had they been proposed domestically, right? Well, as it turns out, that’s not the case.

In the past couple of months, the advocacy of enhanced national security measures domestically has become normalized. This new domestic war on terror has many similarities to the global war on terror, the most obvious being that it was the result of a flashpoint event. In 2001, it was 9/11. In 2021, it was the Jan. 6 Capital riot. Let me be clear: this is not an attempt to downplay either of these incidents. Both were incredibly consequential events that understandably incited fears among large swaths of the American population. In both cases, those fears were then capitalized upon by the intelligence community and politicians alike to advocate for enhanced national security measures with little to no pushback. In the latter case, those new measures came quick and fast. No-fly lists — one of the most draconian aspects of the first war on terror — have been reintroduced, President Biden immediately made it his priority to pass new domestic terror legislation, 25,000 national guard troops were quartered in DC prior to the inauguration, and Congress approved a $2.1 billion increase in Capitol police funding. The White House even considered using private firms to monitor private online chatter of “extremist” groups. With no formal definition of who is and isn’t considered an extremist, this is a clear violation of the first amendment. These measures are not only dangerous, but they’re also completely unnecessary. Domestic terrorism is already illegal, the attacks on Jan. 6th were planned out in the open (online, that is), and the police had a perfectly adequate amount of funding to thwart the attacks, yet were unprepared.

The most significant part of this development, however, is the willingness of journalists not only to be apathetic towards the matter, but to actively join the intelligence community in pursuing it. John Brennan and John Bolton have become frequent contributors to CNN and MSNBC, many journalists have infiltrated private messaging apps and several articles and segments have popped up about the dangers of podcasts and independent media in general. It is this kind of reporting that will be used to justify an eventual expansion of the security state. While journalists are supposed to be punching up and challenging America’s true power centers, it seems as if many have given in to their short-term interests of combating Trumpism.

None of this is to say that white supremacy and domestic violence are nonexistent. They were on clear and full display on Jan. 6th. Yet, an attitude of naivety towards the intelligence community who did so much damage just a decade ago is not a way to combat that problem. (If anything, a domestic war on terror will most likely have a disproportionate impact on people of color.) No matter who the intended target of the intelligence agencies is, we must accept the fact that these agencies are potential threats in their own right, and are not to be instantly trusted.