Attempt to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom divides Californians

June 5, 2021

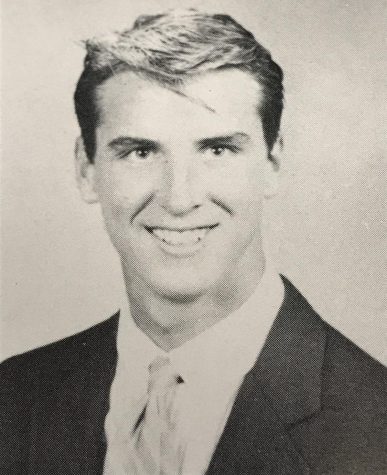

After only two years in office as California’s 40th governor, Redwood alum Gavin Newsom faces his first electoral challenge in the form of a recall. It is the 180th attempted recall of a California elected official and if successful, the recall will force Newsom out of office one year prior to the end of his first term.

Since 2019, there have been multiple attempts to recall Newsom, but the current movement began to gain momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily due to Newsom attending a French Laundry party, violating his own COVID-19 guidelines. In June of 2020, then Secretary of State, Alex Padilla, approved a petition for a recall, giving petitioners until March 17, 2021, to gain at least two million signatures. By the time the deadline arrived, the petition had surpassed two million, collecting nearly 2,117,000 signatures and solidifying a gubernatorial recall election that will occur this year on an undetermined date.

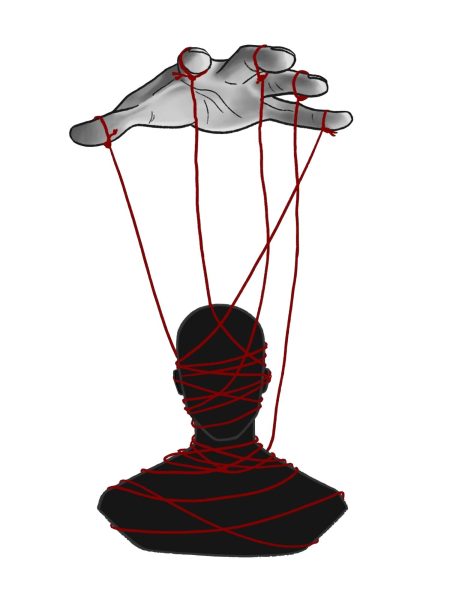

While the recall campaign has focused on numerous issues, its main grievance has been Newsom’s executive overreach. Mike Netter, one of the recall campaign’s leading proponents, expresses particular concern, believing that executive orders issued by Newsom violated the deomocratic will of Californians.

“Newsom really doesn’t listen to the will of the people. In fact, he doesn’t even communicate with the state legislature. He started issuing executive orders long before COVID-19 that violated what we voted for,” Netter said.

Among those executive orders mentioned by Netter was Newsom placing a state moratorium on the death penalty. This decision was not in line with the failure of Proposition 62, a proposition to repeal the death penalty in 2016.

“That was a big trigger for a lot of people that showed [that] this governor was going to try to do what he wanted [not what they wanted],” Netter said.

Another point of frustration for recall supporters is Newsom’s management of the budget. Mike Grover Coltharp, a former San Francisco police officer and candidate in the recall election, is particularly concerned with where taxpayer dollars have been spent.

“We’re paying extra money in taxes that are supposed to go directly to [building] roads, and our roads are horrible, and taxes are not being spent where the California constitution says they’re supposed to go,” Coltharp said. “For instance, our schools have a constitutional minimum amount of money that is supposed to go towards them, and [Newsom] has no problem talking about differing that money until next year.”

While the aforementioned issues have long been an inflection point for Newsom’s critics, it was his response to the COVID-19 pandemic that really accelerated the recall movement due to his inconsistent policies, according to Netter.

“The state was very confused in the counties and cities as to, ‘Are we open?,’ ‘Are we closed?,’ What’s the criteria?” Netter said.

While the majority of petitioners are registered Republicans, the recall campaign has made it clear that their movement transcends political parties.

“The problem we have in politics today is polarization, but we are getting people from the right and the left to talk about the common problems that we want to solve,” Netter said. “[The recall effort] is not a Republican led drive. This has been a people’s movement.”

Though the recall effort has succeeded in making the election happen, polls frequently show that the majority of Californians plan to vote in opposition to the recall. A new poll from University of California, Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies shows that 46 percent of California voters plan to vote in opposition to the recall, with only 36 percent planning to vote in favor. Several opponents, including the chair of the Marin Democrats Outreach Committee Pat Johnstone, see the recall as an expression of Republican greed.

“Republicans have not been able to win state races for a while, and they’re trying to undo an election with this recall using the politics of fear to get it on the ballot,” Johnstone said.

Another particular concern for Johnstone was how the recall campaign has used the pandemic as leverage to air their grievances.

“We’re in a pandemic, we’re in a time when people are afraid on so many levels and [the recall effort] just gives people someone to blame, and I wouldn’t be surprised if many who signed are willing to recant at this point, and by the time we get to the election, I think we’ll realize that this whole recall process is a sham,” Johnstone said.

While California has long been a Democratic stronghold, and it seems unlikely that the recall effort will be successful, the vote itself implies California may not be as politically homogeneous as past election results may suggest. With the election date unknown, yet rumored to take place sometime in November, we will get another clear indicator of California’s overall political climate.