The world’s problems don’t disappear just because your Instagram stories do

March 21, 2021

After George Floyd’s tragic death last spring, it seemed the entire nation turned to social media to show their support and demand change in our police system. However, what began as a way to educate the general public slowly turned ingenuine, giving birth to a phenomenon called performative activism.

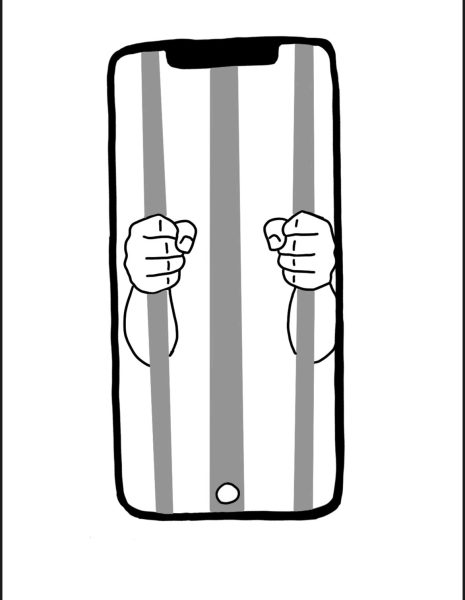

The Oxford English Dictionary defines slacktivism, the slang term for performative activism, as advocacy performed online for personal satisfaction to support political or social causes that require little time, effort or commitment. Whether they want to feel better about themselves or are worried about not appearing “woke,” the byword for being socially aware, enough, performative activists hurt social justice movements. By treating activism as a social phase, people are taking advantage of unfortunate situations and diminishing the momentum of social movements.

S ince we use social media to spread instant awareness of whatever we want, there will always be a performative aspect to it. However, compared to previous campaigns such as climate change and political elections, performative activism reached unprecedented heights during the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement this summer, with #blacklivesmatter being used an average of 3.7 million times a day on Twitter from May 2020 to June 2020, according to Pew Research Center. As BLM activism increased across the internet, new topics began spreading like wildfire across social media.

ince we use social media to spread instant awareness of whatever we want, there will always be a performative aspect to it. However, compared to previous campaigns such as climate change and political elections, performative activism reached unprecedented heights during the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement this summer, with #blacklivesmatter being used an average of 3.7 million times a day on Twitter from May 2020 to June 2020, according to Pew Research Center. As BLM activism increased across the internet, new topics began spreading like wildfire across social media.

Platforms like Instagram went from beautiful sunset pictures and smiling friends to extremely contrasting pictures of Hello Kitty holding “All Cops Are Bastards” signs and text posts with slogans like, “If you vote for Trump, you’re racist.” As the performative activism movement grew seemingly out of control, more posts started appearing on additional media platforms. TikTok videos began circulating with people dancing to audios of other people chanting against the police at protests during the BLM rallies. While entertaining, these videos did little to actually help the movement. In fact, a February Nonfiction survey found that 72.2 percent of students post about political or social issues, but only 2.5 percent of these students believe their posts have a significant impact.

It’s clear the increase of performative activism fosters an environment that supports posts with no fundamental value. Often, social media activism involves the reposting of infographics or snippets of news stories regarding a specific event that does not redirect viewers to platforms where they can contribute to the solution, such as petition links or bail funds. Because of this lack of direction, viewers are not inclined to take action, rendering the posts useless.

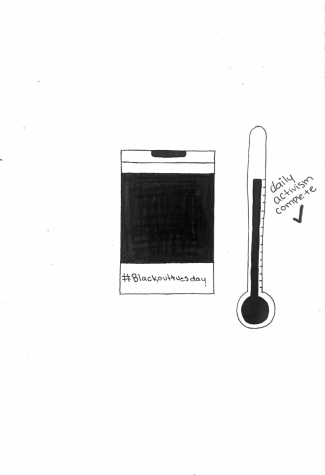

On June 2, 2020, approximately 14.6 million posts of black screens captioned #blackouttuesday and #blacklivesmatter flooded Instagram feeds, according to Google Trends. Originally, Blackout Tuesday was meant to provide a platform for people of color to speak out about their racism experiences. Instead, it turned into a day of meaningless performative activism, as a new “trend” emerged to post a black screen with the caption #blackouttuesday. Because of this, the hashtag #blacklivesmatter was overloaded with black squares rather than posts with tangible information and resources, according to CNN.

As the U.S. underwent a turbulent period of social movements this past year, hundreds of social justice issues were exposed, including women’s rights, indigenous rights, healthcare discrepancies and LGBTQ+ rights, to name a few. Reddit recorded a 40 percent yearly increase in their politics channel this past year, and two of the most upvoted posts were about police brutality. This increase in social media activism regarding various issues created a sense of peer pressure, which can be the most powerful motivator in behavior, according to Tina Rosenburg, who wrote “Join the Club,” a book about the driving forces of activists. As a matter of fact, public opinion plays a large role in how people feel about certain topics. According to a Democracy Fund and UCLA Nationscape Project, as public outrage and BLM protests died down last summer, the number of people who acknowledged the issue of police brutality and had an unfavorable view of the police decreased from 72 percent to 61 percent from May 2020 to June 2020.

On Blackout Tuesday, I witnessed firsthand what it was like to be influenced by peer pressure. As my Instagram feed populated with my peers’ blackout posts, I began feeling insecure about my decision not to. Rather than posting a trivial picture, I signed petitions and made a promise to myself to be actively anti-racist by increasing my education on law enforcement reform and racism. While people may have assumed that my passion for law enforcement reform wasn’t as strong compared to my peers because they posted and I didn’t, my actions have had an active influence on my life and those who surround me.

While performative activism may occasionally spread awareness and information, it makes no changes to the systemic abuses ingrained in our society. Joseph Watson Jr., director of University of Georgia’s Public Affairs Communications program, states, “There tends to be more noise [on social media] than there is actual constructive content or things that facilitate positive and constructive action.”

There are countless websites that provide ways to help the BLM movement and support law enforcement reform without using social media. Jen Shradie, assistant professor of Sociology of Change, acknowledges social media’s potential but says there needs to be more structure and organization for social media activism to be effective. When people use social media activism as their only source of advocacy, they are not achieving much. That being said, social media can be a powerful tool if paired with other formats of activism, such as signing petitions, organizing protests, and helping allocate resources.