Why Jane did not report sexual misconduct

May 15, 2020

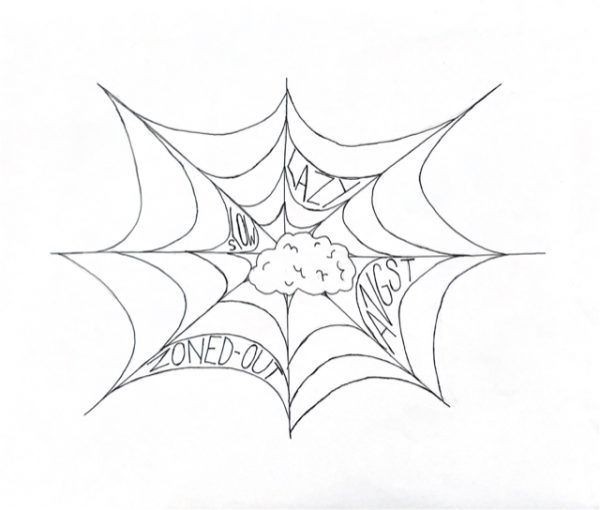

When Jane was a freshman, a rumor spread around multiple Tamalpais Union High School District (TUHSD) schools that she was involved in a threesome with a male student she had been hooking up with and another female student. When she was a sophomore, a boy in her grade tried to kiss her multiple times at a kickback, and she felt the need to resort to physical methods to defend herself. Last year, a male friend masturbated while giving her what she thought was a casual shoulder massage. Jane, now a current senior in the TUHSD whose name has been changed for anonymity, has no shortage of non consensual and uncomfortable sexual stories. Although these experiences have caused strained relationships between friends, subsequent uncomfortable encounters with the other parties involved and emotional stress, Jane has never considered reporting the incidents to a school official.

“I’m a very low-key person and I don’t think [school officials] would have handled it in a good manner,” Jane said. “Imagine if everyone in my school found out about [the sexual encounters].”

Sexual harassment and assault are a daily occurence in American high schools, with 48 percent of students experiencing some instance of harassment each school year, according to the American Association of University Women (AAUW). According to a self-reported Bark survey, 31 percent of Redwood students have witnessed sexual harassment or assault. Yet only 15 percent have filed a complaint to the school’s administration. Out of the surveyed individuals who filed a complaint, only 26.7 percent felt that their situations were adequately addressed. While it is difficult to determine specific causes of the disconnect between sexual harassment complaints and an appropriate response from school administration, under Title IX, schools are legally liable when they know of sexual harassment but do not address it.

It is no secret that a minority of incidents involving sexual harassment or assault are reported to school administrations, a fact recognized by TUHSD principals.

“Absolutely not [are all incidents of sexual misconduct reported]. And as a woman, I can tell you it’s not,” said Liz Seabury, Principal of Drake High School.

Begining in the spring of 2018 following “a public outcry and pleas for help from teachers about sexual harassment,” according to the Marin Independent Journal, TUHSD implemented standardized teacher training and class presentations across schools in the district in an effort to prevent sexual harassment. However, besides these resources and a vague list of procedures provided by the Marin County Office of Education (MCOE), not much is standard about how school administrators respond to sexual harassment and assault allegations. Instead, administrators and district coordinators rely on a “case-by-case” basis to determine the course of action and appropriate punishment following a sexual harassment or assault claim, according to TUHSD principals Seabury, JC Farr (Tamalpais High School Principal) and David Sondheim (Redwood High School Principal). With no strict policy in place, are victims assured that their concerns will be adequately addressed and is there room for inappropriate actions to fall through the cracks?